Footnotes on the Fictive Present, Public Program Series by Adam HajYahia

Sun, Jun 4, 2023

12:00 AM–12:30 AM

Aesthetics and politics have invariably been interlocutors, with a dual relation of antagonism and harmony. Repressive nationalist ideologies have long instrumentalized imagination with the aim of manufacturing a collective identity or a common enemy, while revolutionary political movements have utilized imaginative thinking for the purpose of constructing new social, economic, and political orders. The historicized twinning of the two may be considered emancipatory as much as it is fascist, yet it appears as if the obsession with the political potential of imagination and aesthetics has come to be a modern vocation. Tali Keren’s work poses a set of questions that reveal the history of imagination’s subjugation to violence, particularly settler colonialism, by puncturing a mystified past-future imagination, turning it on its head.

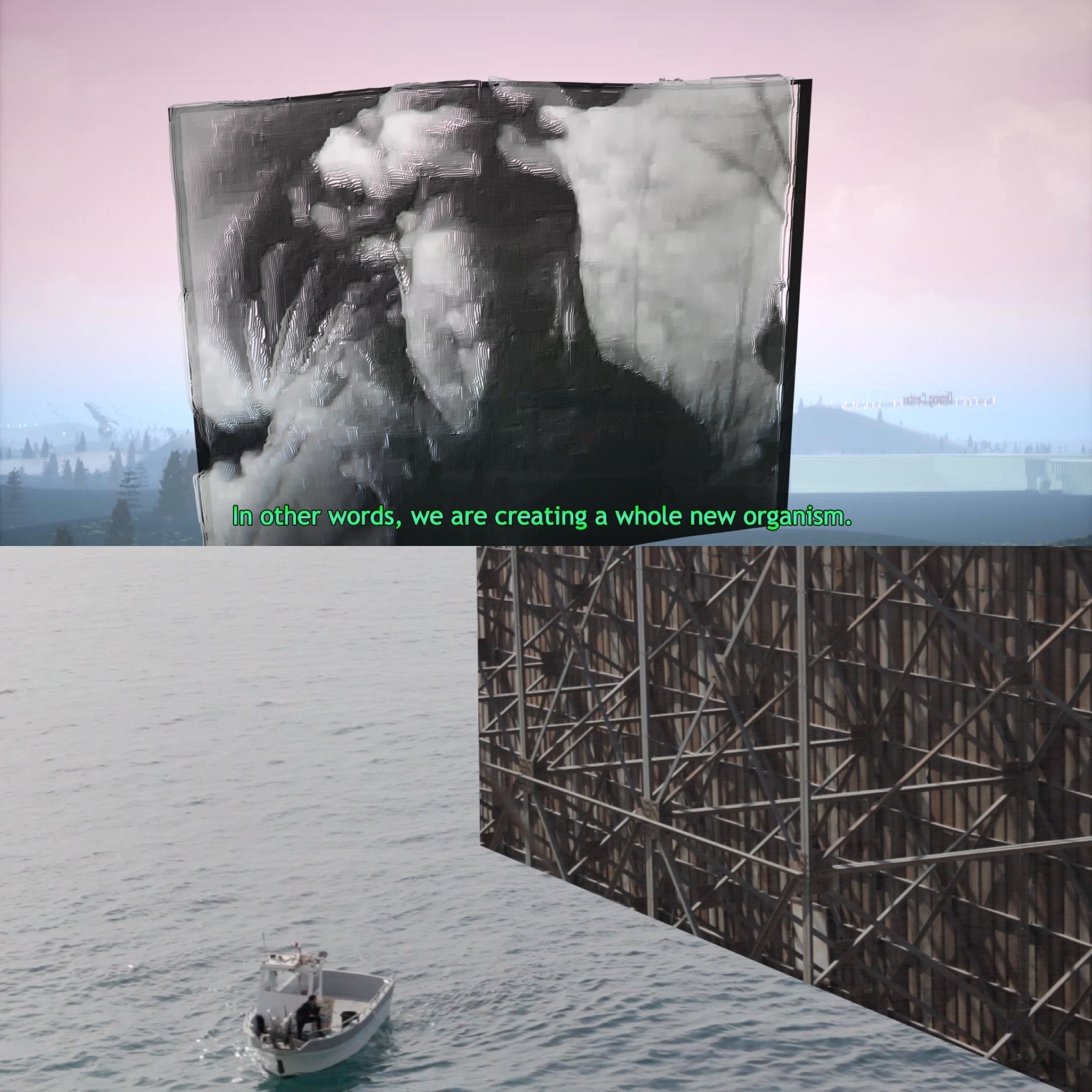

In Un-Charting, a celestial artificial video-game-like landscape emerges, advanced by the soft voice of a young English boy narrating the words of Richard Brothers. Blurring the boundaries between fiction and reality, the film breathes life into Brothers’ foundational colonial text in British Israelism, A Revealed Knowledge of the Prophecies and Times, which was written during his settlement in the Inuit Nunangat lands. In this text, Brothers lays out his imagination of establishing the “New London” in Jerusalem, despite him having never been there. The film turns to the contemporary concomitant relations between Christians in the US and Jews in Israel, revealing the many layers of colonially incestuous imaginations and the

theological constructions of settler-colonial sovereignty. Uncharting moves from the localized nuances of Zionism in Palestine to recontextualize the establishment of Israel within a larger framework of the European settler-colonial and theological imaginary, acting out the fantasy of colonial conquest and imperial plunder.

The purpose of this public program is to respond to, challenge, and complicate these questions, not only in the particular context of Palestine as a geography, but also within larger frameworks that relate to it as a homologous microcosm. In the same manner that Keren problematizes the settler-colonial imaginary in Palestine, linking it to Judeo-Christian theological traditions that preceded Zionism and maybe even contributed to its crystallization, we seek to expand the linkage between imagination and politics and ask: Does imagination as an intangible practice possess the ability to banish material structures such as militarized colonization? Can it be a palpable threat in the face of colonial settlement? If colonists enact their fantasy of conquest, why can’t our fantasy of emancipation and the abolition of power carry the same prospects?

Inaugurating the program, photographer and writer Nour Annan opens with a materialist reading of Lebanon’s Golden Age photographs. In her talk The golden age is out of joint, Annan scours archival images from Beirut’s imagined fantastical past, a prosperous post-colonial era that seduces the viewer from the cataclysm of the present. Using Walter Benjamin’s theory of the dialectical image, Annan’s reading seeks to expose the myth of historical progress in modernity. She interprets film photographs as revelatory historical documents, flipping the fantasy against itself. Alternatively, The Golden Age Is Out Of Joint proposes a counter-reading that nurtures the political potential of the Golden Age photograph in imagining a liberatory future dictated by the oppressed. Can the myth turn into a foundation for imagining a different future? Are we able to imagine an attainable world beyond capitalist reproduction, or has the future been colonized as well?

Artist and filmmaker Mona Benyamin decides to approach this question with sharpness and cynicist criticality. Moonscape is a pastiche of uncanniness reminiscent of Lynchian aesthetics, combined with the weightlessness of Arab pop video clips, precisely Jar El Qamar Concert by Sabah Fakhri. In Moonscape, the settler-colonial matrix of Palestine evolves evermore claustrophobic, alienated from Arab culture by material borders that intensify psychological schisms. Yet another colonial configuration encapsulates Benyamin’s escapism, but one of a different nature: the Moon. Through her eager attempts to obtain a passport from the Lunar Embassy to replace her ‘contaminated’ Israeli one, the protagonist’s imagination becomes as colonized and restricted as her native land, and the possibilities of breaking out of these militarized regimes are narrowed. The film eloquently tackles the diasporic condition of alienated Palestinians living in their homeland, while paying sensible attention to the reigning forces that govern our ability to imagine an alternative.

The settler-colonial project, as history demonstrates, necessitates the conceptualization of “nature” and “culture” and the assertion of control over them. It both enforces their demarcation from one another and from the native population that they are part of. Thus, no critique of the settler colonial project can suffice without a materialist analysis that obfuscates the hegemony of capital over land and the exploitation of its inhabitants.

Visual artist and writer Bahar Noorizadeh knows this all too well. In The Red City of the Planet of Capitalism, Noorizadeh revisits Disurbanism – a socialist architectural project developed by Mikhail Okhitovich and Moisei Ginzburg in the Soviet Union in 1929. The film is narrated through a letter that Okhitovich wrote to Le Corbusier, explaining to him why the dismantling of capitalism cannot occur through the “healing” of the modern city, but rather its disurbanization. At the crux of such postulation lies the aim of building a horizontal infrastructure that balances the disparities between the city as the center and the countryside as peripheral. That way, Okhitovich writes, both the peasantry and the workers will have the same access to resources and cultural engagement. Noorizadeh’s film does not take this literature at face value. Her audiovisual interpretation of a cybernetic imaginary of Soviet socialism does not romanticize the good old days, but instead works with the technological advancements of our time. It is both an attempt to liberate society from financialized cities and peripheralized villages, and to emancipate modern technology from the grips of capital.

Most imaginaries are examined through their intangibility. But what about their embodiment? Their carnality? Their phantasmic potential as somatic and sensorial practice? Music and sound are ethereal, yet their receptive and productive characteristics are embedded in a political and revolutionary economy. The transmission of waves from intangible matter into active movement, dance, and protest is indomitable, commanding assembly and disrupting latency.Dream Riots is a live musical performance by multi-disciplinary artists Bergsonist (Selwa Abd) and Gavilán Rayna Russom. Their sonic weavings blur the lines between audience and performer, interrupting the public program with a temporary moment of collectivity. Opening the evening, Bergsonist’s musical approach centers on abstraction, intuition, and repetition as modes of assembling a revolutionary aesthetic. Her musical performance is a meditation on the varied processes of creation and freedom. Moving across radiant soundscapes, Gavilán Rayna Russom’s performance projects from the axis points between the living and the dead. Rayna’s mixes pose stealthy challenges to the whitening of sound through the use of sonic portals that create space for different tones, distortion, sonic abstraction, and ghost frequencies. Harmonious at times, and antagonistic at others, the musicians form a realm where imagination is not a mere psychic occupation, but a somatic and sensorial embodiment of possibilities.

Participants

Related Events

Conversation & Screening

“The Red City of the Planet of Capitalism” + “Gazing… Unseeing” screenings followed by a conversation between Ali Al Adawy and Adam HajYahia

Performance

Dream Riots Musical Performance with Bergsonist and Gavilán Rayna Russom

Conversation & Screening

Screening of Moonscape by Mona Benyamin followed by a conversation with Tali Keren