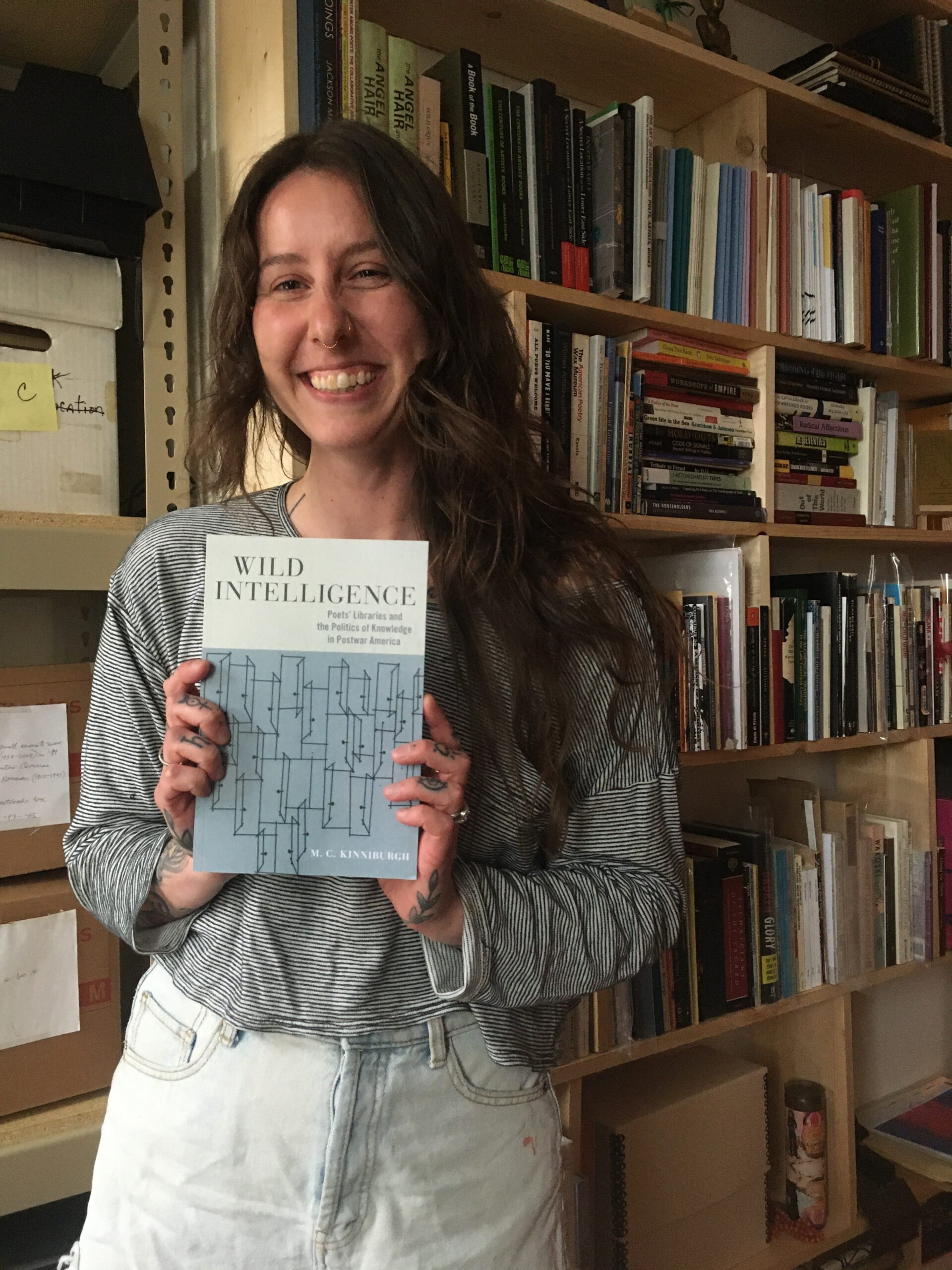

Wild Intelligence: An Interview with Lost & Found editor M. C. Kinniburgh about her new book on poets’ libraries

June 1, 2022

Lost & Found General Editor Ammiel Alcalay interviews Lost & Found Editor Mary Catherine Kinniburgh on the origins and journey from CUNY Graduate Center student and Lost & Found scholar to her present position as partner with Granary Books—and the book that she wrote along the way. Her new book Wild Intelligence: Poets’ Libraries and the Politics of Knowledge in Postwar America published by University of Massachusetts Press in collaboration with Lost & Found Elsewhere takes up case studies of four poets and their libraries: Charles Olson (1910–1970), Diane di Prima (1934–2020), Gerrit Lansing (1928–2018), and Audre Lorde (1934–1992). Kinniburgh shows that the postwar American poet’s library should not just be understood according to individual books within their collection but rather as an archival resource that reveals how poets managed knowledge in a growing era of information overload. Exploring traditions and systems that had been overlooked, buried, occulted, or censored, these poets sought to recover a sense of history and chart a way forward; Kinniburgh seeks to tell their story.

Ammiel Alcalay (AA): Congratulations on your new book Wild Intelligence! Before I ask you about specific libraries you’ve written about, can you take us on a quick journey through how you came to write this book?

Mary Catherine Kinniburgh (MCK): Thank you! I wrote this book to document what I saw as I stepped through professional and intellectual doorways, via the world of books and archives. My trajectory from graduate student, to archivist and rare book librarian at the New York Public Library, to archives and rare books dealer and publisher at Granary Books, meant that I participated in a sort of “water cycle” of the contemporary knowledge ecosystem: how books or collections get made, preserved, and encountered (or not). I’m really interested in the practical work of this—what needs to get done to make sense of things and take good care of them—and the book stemmed directly from that orientation.

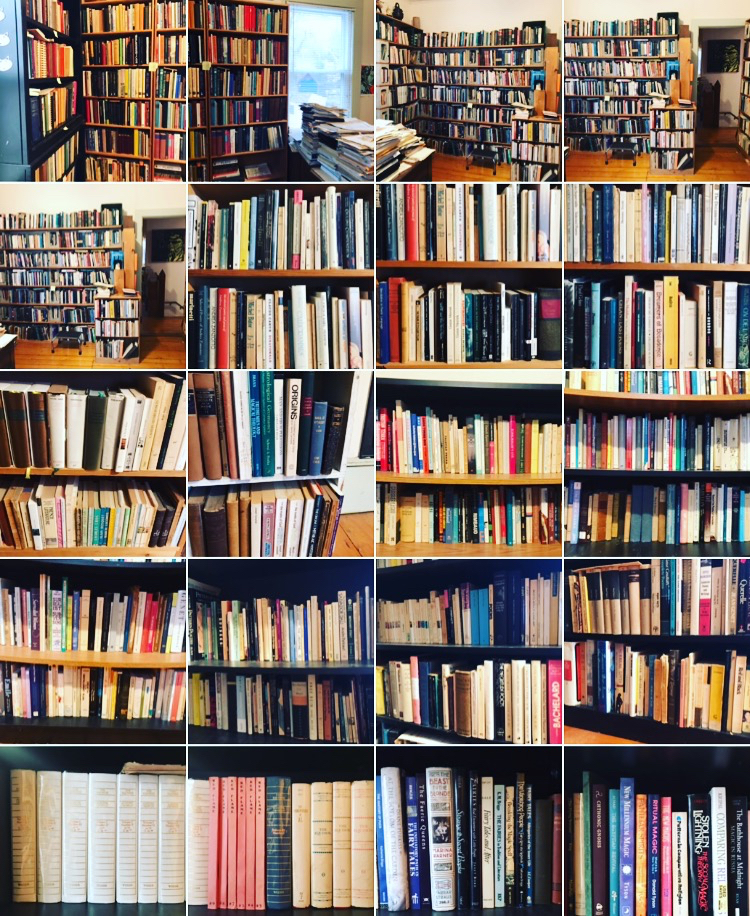

One of the first gateways to this world was when you connected me with the Maud/Olson Library in Gloucester, MA. Seeing how Ralph Maud built and conceptualized Charles Olson’s reading library as an archival fonds, a collation of evidence, struck me as a very useful way to understand a poet not just based on their work, but their life. I began writing about this for my dissertation, and continued to visit poets (like Diane di Prima and Gerrit Lansing, via the auspices of Lost & Found). The more poets I met, the more bookshelves I saw. Not every poet has a library, but for the ones that do, certain patterns present themselves about how, why, and which books are collected.

AA: You mention Lost & Found, and your work trajectory from archivist and rare book librarian at the NYPL to your present position at Granary, a position that would be defined these days as a “non-academic” or alt-ac” endeavor. Yet your book has been published by the wonderful University of Massachusetts series Studies in Print Culture and the History of the Book (in collaboration with Lost & Found Elsewhere). Can you talk about how your work at the CUNY Graduate Center, and through Lost & Found, prepared you for these possibly unexpected places you got to?

MCK: The English Program at the CUNY Graduate Center was a wonderful intellectual home base for me. Our department fostered creative thinking about the research and work I could do as I followed the path of poetry, as well as some serious professional development opportunities. For a number of years I was a Digital Fellow, in the program built out by Matthew K. Gold and with Lisa Rhody, and that honed my project management skills and thinking about textuality in a digital era—both assets in my career trajectory. Fellowships (in terms of financial and community support) with Lost & Found allowed me to travel the country and meet librarians and archivists for my research, as well as poets I was studying.

And coursework with professors like Wayne Koestenbaum, journaling about trance and watching Stan Brakhage’s Moth Light and of course, you—how you’d show up to class weighed down with dozens of small press books and mimeo-era magazines each session—there was genuine enthusiasm that I felt from our community about literature beyond the mainstream, beyond traditional modes of critique. Freed of the pressure to “be academic,” I could instead focus on the integrity of my research and my work, and see where it led on its own terms.

AA: There is a wonderful symmetry in the four chapters of your book because of the personal relationships among the people you write about: the middle chapters are about Audre Lorde and Diane di Prima who, of course, were extremely close throughout their lives, starting out as classmates at Hunter High School. The bookend chapters are about Charles Olson and Gerrit Lansing, who were very close. And of course Diane has written extensively about her encounters with Olson and she was also very close to Gerrit. I remember when I told you that you needed to go to Gloucester and visit Gerrit, as he wasn’t getting any younger though, as you know, it always seemed like he was! Not everyone takes that kind of advice, but you did. Can you say something about that in relation to our Lost & Found motto, to “follow the person.”

MCK: Well, you’ll remember that when we first met, I was pursuing medieval studies. I joined the planet over a thousand years too late to meet those poets, so it was a little terrifying to realize that I was going to have to have conversations and get to know poets personally!

As with any intergenerational relationship, visiting our poetic elders means we get to share in their wisdom, and experience their truth about the relationships and poetry that they created. This lets us punch through the false, clique-ish narratives about poetic movements and “schools,” and see who really hung out, babysat each others’ kids, organized fundraisers for electric bills, played impromptu baseball. Visiting a poet’s archive and reading their unpublished letters and manuscripts is also a good way to do this, but when there’s an opportunity to say hello in person: just take it. That chance won’t exist forever.

Beyond this, to me, the “follow the person” motto, taken literally, is an ethical stance. It argues that poetry is one big breathing thing, and that we are accountable to each other. Why should I say my two cents about a poet in a research paper if I’m not willing to visit them, bring them a sandwich or some notepads, have a conversation? This belief was what originally helped me screw up the courage to speak with people I admired, but once I did so, I was struck by their hospitality, and of course, by their bookshelves. If I hadn’t gone to visit Diane di Prima or Gerrit Lansing, I wouldn’t have observed the primary sources—their stunning libraries—that inspired my book and professional life.

Watch the recording of Mary Catherine Kinniburgh‘s, lecture about her new book Wild Intelligence: Poets’ Libraries and the Politics of Knowledge in Postwar America, hosted by the Grolier Club. Kinniburgh will discuss her new book which includes the Maud/Olson Library and explores how the characteristics of 20th-century counterculture poets’ libraries shed light on the history of information management and knowledge preservation, and underscore the idea that a life of poetry (and perhaps even book-collecting!) is a political and spiritual act. The event is also available to watch on the Grolier Club’s Vimeo Channel. Watch the lecture here: