“What are we asking from Lucretia? What work do we need this tape to do?”

June 21, 2019

Kyle Croft

The Visual AIDS Archive Project was co-founded by painter Frank Moore and writer David Hirsh in 1994 to document the work of artists living with HIV, who were dying too quickly, too young, and without estate planning. In the twenty-five years since then, Visual AIDS has continued to work to preserve these legacies and to support artists living with HIV. As part of our commitments to access and visibility, along with preservation, Visual AIDS re-launched its archive online in 2012 as the Artist+ Registry.

Over the past two years, I have participated in the VHS Archives Working Group representing Visual AIDS. We have all been thinking about how to ethically steward communities, feelings, and histories in analog archives from queer communities, and I have been engaged with the task of considering these questions for the legacies, art, and artists currently housed in Visual AIDS’ Artist+ Registry. In particular, we have discussed what to do with video archives and how to facilitate community-based care and engagement from them. Together, we have been working to figure out how this digitally inspired “caring.sharing” can be best enacted in a communal, event-based setting (what we have called “parties”). Throughout the process, Partners & Partners has been working with us to design and refine a web-based tool that can both structure these activities and hold the ideas, thoughts, and connections that come out of them.

The aim of our work is to leverage historical materials as prompts for present-day activity, allowing contemporary concerns to animate these analog archives while remaining intentional about how we are shifting the context, access, and visibility of these tapes.

***

For our March meeting, I screened a few excerpts from a VHS tape as a case study for how these “parties” might work. The tape I screened holds an interview with Lucretia Critchlow, one of the first Artist Members of Visual AIDS. David Hirsh recently sent us this interview along with several dozen other tapes that he shot during the mid-1990s with various artists living with HIV, most of whom have no other historical record and have since passed.

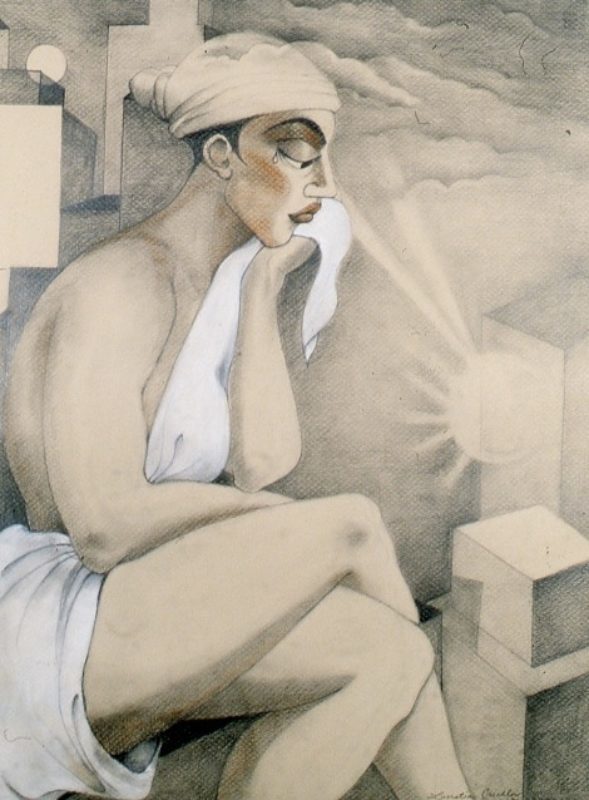

In the Visual AIDS Archive, we have a folder with Lucretia’s name. It contains a number of slides documenting her drawings, many of which prominently feature female figures radiating with light. There’s also a signed registration form from when she joined the Archive. Lucretia’s work was included in The First 10, an exhibition of the original group of artists to join the Archive Project. A small thumbnail portrait of her appears in the black and white catalog that was published for the show. Until we received the Hirsh interview, this was the extent of the information we had about Lucretia. My former colleagues had been in touch with some of her family, but we didn’t know if any of her work is extant.

For my “party,” I invited my colleagues at Visual AIDS and some other community members to join the working group for an evening. Together we looked at Lucretia’s page on the Visual AIDS Artist+ Registry to get a sense of her artwork. Then we watched some excerpts of the tape together. (I also emailed her family in hopes that they might be able to join.)

The interview is long, filling an entire two-hour VHS tape, and ranges from childhood biography to artistic inspirations and spiritual reflection. Lucretia talks about her growth as an artist, attending FIT and studying fashion illustration, working in the fashion industry, and eventually getting burnt out due to exploitative labor practices.

I was excited to have and share this rich primary source about Lucretia—it offers a wealth of information about her life and artwork. As an art historian, my first impulse is to identify and interpret any available information from a primary source, and to use it as evidence in order to construct an argument about how an artist or artwork fits into larger historical narratives. By studying this tape, I hoped that Lucretia and her work might receive deserved attention and begin to be acknowledged in cultural histories of her time. This kind of intervention into historical narratives is a central aspect of our work at Visual AIDS, particularly in the last several years, as AIDS activist histories are receiving widespread revisitation.

But I sometimes feel uneasy about this work of historical revision, especially when the values and assumptions of art history—genius, masterpieces, the canon—don’t resonate with the artist’s own aims. My thinking around this quandary has been enriched by an essay about curating the “outsider” artist Ronald Lockett written by Katherine Jentleson and Thomas Lax.[1] While cautioning against attempts to seamlessly integrate Lockett into a grand art historical narrative, Jentleson and Lax propose a series of unlikely pairings for Lockett’s work, placing him alongside Felix Gonzalez-Torres, fierce pussy, and Group Material. In avoiding over-determinations of Lockett in terms of identity, geography, or chronology, Jentleson and Lax instead seek resonances in how these artists engage and grapple with the world around them.

Inspired by this approach, I brought Lucretia’s folder from the Visual AIDS archive to the meeting, along with books, ephemera, and other archival material relating to a number of other artists in the Archive—Chloe Dzubilo, Antonio Lopez, Affrekka Jefferson, Ronald Lockett, and Joyce McDonald. I asked my collaborators to leaf through these materials and prompted them to consider who we might consider to be a contemporary of Lucretia. How does she relate to the other artists in the archive? The point wasn’t to argue that Lucretia is the next Antonio Lopez but rather to situate her in a web of relations, both historical and speculative, that might shed new light on Lucretia (and ourselves, in the process).

One of the aims of the web-based tool that we are designing with Partners & Partners is to hold the connections that come out of these conversations, allowing communities to annotate videos with rich metadata: text, images, links, maps, and even other videos. We hope that this provides an attractive and user-friendly way to identify, organize, and supplement historical information embedded in any tape, providing entry-points for art historians and researchers. For example, we could overlay the interview with research about who else was studying at FIT alongside Lucretia, correlate her personal history with the epidemiological history of AIDS in New York, or cross-reference it with the biographies and archival materials of other artists in the Registry.

* * *

It turns out, like the ideas that motivate our working group, this tape is a meditation on self-expression, affirmation, and vulnerability. Lucretia reflects on her HIV diagnosis, her relationship to her family, and the challenge of finding her own voice amidst the tumult of her life. As she’s discussing private aspects of her life, she reflects on how vulnerability works in different contexts, noting that she is comfortable sharing some stories one-on-one with David but wouldn’t want that information to be shared publicly. Her art practice provides her a way of negotiating this vulnerability, first allowing her to see herself and her emotions reflected on paper, and then giving her a format for deciding if she is ready for those expressions to be shared with a wider public.

Lucretia asks us plainly and also more generally: What do you do with history that doesn’t want to see the light of day? As we sat together and watched her say this, we speculated how Lucretia and David might have understood what they were doing, how they imagined the audience for this tape. Who could have predicted YouTube at that point? Group member Theodore (ted) Kerr offered a helpful prompt, opening our conversation out beyond the art historical, “What are we asking from Lucretia? What work do we need this tape to do?”

Rather than downplay our roles as historians, interpreters, or cultural workers, Ted was asking us to name and own our stakes in Lucretia’s videotaped art and life. As we sifted through her interview and annotated, interpreted, and summarized it, what are we trying to do?

In shifting the subject of inquiry to ourselves, what might have been more commonly considered a secondary source (our interpretations of the video) becomes a new primary source.

This shift gets at the heart of our work in the VHS Archives Working Group. At the end of our meeting, we brainstormed additional prompts that might generate engagement with this interview. Ideas included re-writing David’s interview questions (what would you want to ask Lucretia today, knowing what and how we do now?) or re-enacting the interview (maybe trying out those revised questions). As we have been designing our tool with Partners & Partners, we have aimed to avoid hierarchies between primary and secondary sources, valuing this kind of speculation and creative re-animation on the same level as historical inquiry. The idea is that these “parties” and the conversations and connections that come out of them are a way of bringing historical materials—specifically video—into the present without placing undue burdens on the subjects that are held within them.

[1] Jentleson, Katherine L., and Thomas J. Lax. “Curating Lockett: An Exhibition History in Two Acts.” In Fever Within: The Art of Ronald Lockett, edited by Bernard L. Herman, 45-60. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016.