About the event

The thematic focus for December’s Climate Action Lab (CAL) session was waste and the ways in which waste systems are deeply connected to race and class-based inequalities in New York City and beyond.

Both presenters of the session touched upon the inequality-reproducing and ineffective structures of existing waste practices and laid out proposals and projects to reform and change them.

The first presenter was Justin Wood from the New York Lawyers for Public Interest (NYPLI). As NYLPI’s Director of Organizing and Strategic Research, Wood develops and executes advocacy and legislative campaigns in partnership with grassroots community partners. He is also a Taconic Fellow in NYLPI’s Environmental Justice program and has been a leader of the Transform Don’t Trash NYC coalition and other campaigns to reform the city’s solid waste management system since joining NYLPI in 2014. Wood’s talk outlined the goals of a commercial waste system reform plan “Transform Don’t Trash NYC.”

Wood asserted that NYLPI’s waste hauling reform aims to provide justice, equity, and benefits such as reducing truck traffic associated with the commercial waste business, improving safety, creating fair and predictable pricing, and cutting greenhouse gas and air pollutant emissions. The bill, as Wood explained, will help ensure that low-income neighborhoods are not unfairly targeted by waste transfer businesses, given that a historical overabundance of waste hauling in these overburdened communities has led to dangerous truck traffic, abysmal air quality, disproportionately high asthma rates, and noise pollution. This industry has low recycling rates, poor conditions for workers, unfair siting of waste transfer stations, and a lack of oversight, Wood added.

Wood then showed the participants detailed maps of the waste routes of private company trucks, adding that each private university, bodega, office building, or factory has to find a private waste company to pick up its garbage. He noted that because of this unregulated, capitalist, competitive system, these companies pick up customers from wherever they can. He also outlined the ways in which the current waste system is ineffective and irrational; the current system also means long hours for the drivers, which leads to fatigue driving as well as a large expenditure of diesel oil. Part of the reform proposal to decrease the inefficiencies of the current system is a “zone waste system.” This system consists of 20 zones in the city, and each private waste company collects within a specific zone. As Wood explained, in the proposed system, the truck mileage go down drastically from an estimated 80,000 miles per night to a 30,000. As Wood noted, the proposed model follows the model of the West coast cities such as San Francisco, Seattle, and Los Angeles.

Wood then spoke about the structures of inequity in where the waste goes. As he explained, waste used to go to the giant Fresh Kills landfill, but it was closed after it ran out of space in the 1990s by a Giuliani coalition seeking to earn for the votes of Staten Island. However, Wood explained, what sprung up in its place with very little planning was a system of private waste transfer stations that use diesel trucks. Wood noted that this is one of the most inequitable systems in New York City. In the map Wood showed, the huge tonnage of waste going through North Brooklyn and South Bronx, which have the highest asthma rates in the country, could be clearly seen. As Wood noted, there are schools, parks, and private homes in close proximity to these transfer stations. He made it clear that this situation is closely linked to the motivations of private companies to make a profit and to export waste to out-of-state landfills as cheaply as possible, while NYLPI’s goal is to make the city commit to an equitable form of waste export.

Wood noted that one of their most ambitious projects is to try to get the commercial private haulers to start taking waste to transfer stations at night, which would be preferable to the current system. Their second goal is to address the low recycling rate in the private waste sector. From a greenhouse gas perspective, Wood added, not burying food waste and plastics in landfills is much more burdensome than actual truck emissions. As Wood noted, only %20 of the private waste industry is currently recycling its waste. Moreover, in response to the market challenges caused by China and other countries clamping down on recycling, private haulers are recycling even less now. Wood added that NYLPI’s goal is to make sure that waste reduction becomes a major part of these commercial actors in the city.

Delving into the details of the proposed reform, Wood mentioned that customer education should increase and that there should be some reward for customers who actually cut down on their waste by, for example, bringing their own cups, cutting down on containers, etc. He also added that having safer streets is a major goal of the proposed system, since the fatigue caused by driving long shifts and the irrational routes increase the risk of accidents involving these waste trucks. Wood added that justice for the workers in the commercial waste industry, including wage standards, benefit standards, and safety protections are a part of this reform.

Our second speaker was Brooke Singer, an artist, educator, nonspecialist and collaborator, whose work appears on/as websites, workshops, photographs, maps, installations, public art and performances that often involve participation in pursuit of social change. She is Associate Professor of New Media at Purchase College, State University of New York, a former fellow at Eyebeam Art + Technology Center (2010-11), cofounder of the art, technology and activist group Preemptive Media (2002-2008) and cofounder of La Casita Verde (2013-). Her talk was titled "Art, Inquiry, Action."

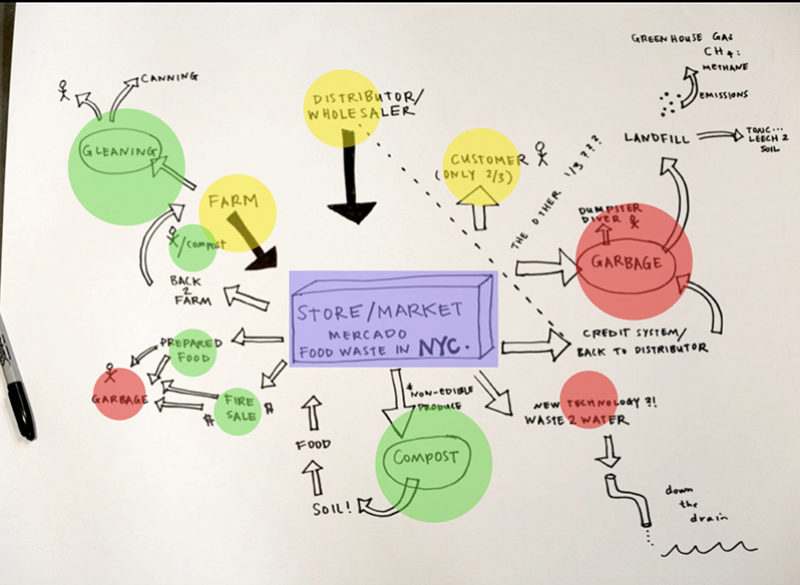

Brooke Singer defined her work as research-based art, as often collaborative, interdisciplinary, and goal oriented. She discussed her project "Excedentes" (2011), which was commissioned by Matadero Madrid Center for Contemporary Creation in Madrid, Spain for a program called El Ranchito. Singer mentioned her work that aimed at connecting edible food waste to people who are hungry and establishing redistribution systems. The result was the setting aside of edible food waste by merchants and restaurants and then displaying this food and encouraging people to take what they need. In efforts to make this work sustainable, Singer noted that they felt the need to bring in a legal structure and involve legal experts in the project. She then talked about the ways in which they had thought about realizing a similar project in New York City, called ExcessNYC, a cargo bike with a “bodega style” food display and a storage unit in the front and a pedal-powered compost tumbler in the back. As part of this project, Singer and her colleagues collected edible food from small grocery stores in order to redistribute them like they did in Madrid, but they also accepted inedible food for compost. Eventually they established a compost garden in Crown Heights, Brooklyn and processed over a ton of organic waste in nine months.

Singer mentioned another project, La Casita Verde (2013), which aimed to establish a more permanent community compost site on a South Williamsburg lot that had been derelict for 40 years. Another project, Carbon Sponge (2017), Singer explained, tests soil in order to assess the quality of the compost they have been making; this involves not only testing toxin levels but also the soil’s microbiological qualities and ways of visualizing or representing this vitality found in the soil.

Singer noted that she is interested in a project that aims to test for lead and other toxins found in community gardens and carbon sequestration of the soil. She described this project as attempting to use or to encourage nature’s system of bringing carbon out of the atmosphere through photosynthesis and creating a symbiotic relationship between microbes and plants, bolstering the microbial community that lives in these soils. In this way, Singer suggested, “dirt” can be a part of the solution to the problems caused by human-induced climate change. Examining the carbon sequestration in urban soils and collecting data on the pH levels, soil temperature, and moisture, this project aims to develop a kit and a protocol for urban gardeners to use and to cultivate planting recommendations. Singer is partnering with a team of scientists at the Urban Soils Lab at Brooklyn College on this project, scientists from the Advanced Scientific Research Center at the Graduate Center, and other public and private collaborators.

Co-sponsored by the Art, Activism, and the Environment research group as part of the Seminar on Public Engagement and Collaborative Research from the Center for the Humanities at the Graduate Center, CUNY; the Occupy Climate Change! Project of the Environmental Humanities Lab at the Royal Technology Institute of Sweden; and the Climate Action Research Cluster of the Social Text Collective.