Iris Cushing

(September 2020)

Before I came to the CUNY Graduate Center as a student, I came to the physical building as a small-press publisher, back when the Chapbook Festival was hosted on the “C level” of the building on 34th St. and 5th Ave. My press, Argos Books, set up a table and participated in the readings and workshops, all of which thrilled me. It didn’t matter that it was springtime outside, and we were in a basement; I was in heaven reading books of poems, talking to other poets and people who made books, and feeling the liveliness of connecting with my poetic kin. (I even recall bringing my sister to a Chapbook Festival and her being somewhat starstruck when Thurston Moore walked past our table. I think this was proof, in her eyes, that poetry really was cool). It was in the context of this motley gathering that I first encountered Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative.

Perusing the books in the first few Lost & Found series, I was stunned to see a few books by one of my lifelong literary heroes, Diane di Prima. Di Prima for me had always been a sort of “code word,” a poet whose presence guaranteed an unmistakable affinity between myself and whoever was reading or talking about (or in this case, publishing) her work. I dove into reading the books in the first three Lost & Found series, especially di Prima’s books: R.D.’s H.D., The Mysteries of Vision: Some Notes on H.D., and di Prima’s Olson Memorial Lecture. In the spring of 2014, I found myself back in my homeland of Northern California for spring break. To my delight, I had just been accepted to CUNY’s English Ph.D. program; I asked Ammiel Alcalay if he could put me in touch with di Prima while I was there in San Francisco.

I visited her on that trip for the first time at her home in the Outer Mission. Meeting di Prima was profound. I was awestruck by her and by what a very real person she was. She was warm and welcoming while also being very no-nonsense, and we spent the day organizing and photocopying a collection of formal poems she’d written as we got to know each other. Talking to her and looking around her house, I was amazed by the extent of her knowledge and by the vastness of her materials: her library, her unpublished manuscripts, her archive, her speaking to me in Latin, recalling alchemical formulas and Tibetan Buddhist mantras. I knew that I wanted to work with her on my doctoral journey, and beyond.

Once I started the English program at the Grad Center, I was assigned to work with Ammiel as his research assistant. This “job” meant getting to scan Ed Sanders’ incredible hand-drawn glyphs and notes for his Olson Lecture, among other things; studying with Ammiel also led me to meet those who would become my dearest scholar-activist-poet family, Mary Catherine Kinniburgh, Iemanjá Brown, William Camponovo, Kendra Sullivan, and Öykü Tekten. Meeting these people was the sweetest kind of intellectual homecoming. I treasured our late nights out at midtown bars talking about the work of di Prima, Amiri Baraka, Gregory Corso, Ed Sanders and Charles Olson. Meanwhile, Ammiel (who right away understood my affinity for tough, independent female poets) keyed me into a few writers I hadn’t heard of before: Judy Grahn, pioneering lesbian feminist poet; Bobby Louise Hawkins, extraordinary poet and prose writer of Western vernacular; and Mary Norbert Korte, a former nun and poet-activist who supposedly lived in the California Redwoods, but who no one had heard from in quite some time.

By the fall of 2015, we were at work planning Series VI of Lost & Found. After a gathering at Kate Tarlow Morgan’s house in rural Marlboro, VT (during which time I was notoriously terrorized by foxes while attempting to sleep on Kate’s trampoline) Will Camponovo and I had zeroed in on Hawkins’ lectures from Naropa University, “The Sounding Word” (1989) and “Collette: Earthly Paradise” (2005). The lectures existed in audio form but had not been transcribed, let alone published. We got to work on transcribing and editing them and marveling at Bobbie Louise’s genius.

Through Reed Bye, I got in touch with Bobbie Louise herself and made a plan to interview her in the retirement home where she lived in Boulder, Colorado. I arrived at Bobbie Louise’s door on Halloween morning, bearing a potted African violet as a gift. At 85, Bobbie was as bright and witty as a bubbling spring. We spent the day in her living room, looking at her paintings, talking about her life, her writing, the voice, and the mysteries of humor. I recorded every word of our conversation, to bring back and transcribe.

In the meantime, Iemanjá and I were looking over Judy Grahn’s Blood, Bread and Roses: How Menstruation Created the World, Grahn’s brilliant study of the connection between women’s menstrual rites and forms of knowledge such as agriculture, calendars, and astronomy. The book had been published in the early 80s by Beacon Press and was out of print. Ammiel had the idea to present some selections from the book in Series VI, and to interview Grahn. In December, Iemanjá and I flew to San Francisco, stayed with my friend Connie in Oakland, and the next day drove in a rented car down to Palo Alto to meet Judy Grahn. Judy and her wife Kris Brandenberger and another friend greeted us gladly at Judy’s house. For many hours we talked about the complex phenomenon of menstruation, its impact on the formation of human culture (especially writing), and other things. As with di Prima and Hawkins, I was dazzled by the breadth of Grahn’s knowledge and her ability to make connections between histories and worldviews. Our time with Grahn confirmed for me my not-so-secret belief that “old” women (in their 70s, 80s, 90s) are actually the smartest people in the world. The editing and writing I did for the two books I edited for Series VI were grounded in the admiration that filled my spirit when I met Hawkins and Grahn.

Judy Grahn and I saw each other again in the spring of 2016, when she and Kris drove down to Los Angeles for the AWP conference. Judy read her poems at a packed gathering at the groovy rental house in Silverlake where some friends and I were staying. She blew the audience away with her singular combination of wit, presence, dazzling knowledge, and deep quietness. That same spring, I was awarded Lost & Found’s Diane di Prima Fellowship and went out to San Francisco for my first extended period of work with Diane that summer. I settled into a friend’s small apartment in the Outer Sunset and spent about a month traveling to Diane and Sheppard’s house almost daily. On that trip, I interviewed Diane extensively about things I’d long wondered about, especially her writing of Memoirs of a Beatnik, her fictionalized erotic memoir (which had a powerful impact on me as a young woman). I helped Diane edit chapters from Grail is a Green Stone, her unpublished autobiography of her life after she left New York City for good in 1968. With Shep’s keen help, I found Diane’s original handwritten notes for her lectures on Percy Bysshe Shelley, which she delivered at The New College of California in 1984, and later at the Poetry Project at St. Marks Place. I returned to New York swirling with ideas for how to activate my own interpretations of di Prima’s work.

I was thrilled to receive the Di Prima Fellowship again in 2017 and 2018 so that I could continue traveling to California to meet with di Prima and explore the trove of materials in her home. I began putting together the concept for a chapbook of di Prima’s lecture, “Prometheus Unbound as a Magickal Working,” a previously-unpublished lecture which proposes that Shelley’s dense, difficult lyrical drama Prometheus Unbound is also secretly a hermetic formula for enacting transformation. I copied the original notes (scrawled on a yellow legal pad) for this lecture on Diane and Shep’s small photocopier and then transcribed them in a café on Mission Street, surrounded by tattooed, bearded San Francisco hipsters. As I typed up Diane and Shelley’s words, I could sense invisible, benevolent forces gathering, exerting themselves upon my imagination.

Meanwhile, Ammiel informed Mary Catherine and me that he had made an exciting discovery. In Michael McClure’s archived papers at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, he had discovered a handwritten manuscript by Mary Norbert Korte. Korte had written a poem on each page of McClure’s book Ghost Tantras––in response to McClure’s guttural, growling “beast language” poems––and sent the response-poems to McClure in January of 1967. Ammiel photographed these sparkling poems, written neatly in all-caps, and emailed them to us; no one, besides McClure and Korte, had apparently seen them before. They leapt out at me in their strangeness, a message from an earlier era. In March of 2017, Joanne Kyger died, and Ammiel got in touch with Bill Ray, a mutual friend of Kyger and Korte’s and a resident of Willits, California. Ray gave Ammiel Mary’s phone number and PO Box mailing address.

Mary Catherine and I hatched a plan to meet Mary Norbert Korte. I called Korte on the phone and introduced myself a couple of weeks before our proposed visit; I was astounded by how glad and welcoming she was, even over a spotty cell phone line. She gave me detailed driving directions to her off-the-grid compound in Irmulco––an unincorporated region deep in the redwood forest of Mendocino County––indicating that we wouldn’t find it on Google Maps. We set a date for our meeting: June 24th. Mary Catherine flew out to SFO from New York sometime in mid-June, and we had a couple of meetings with Diane in San Francisco before our journey up to Mendocino. Diane and Mary, it turns out, were old friends but hadn’t seen each other in decades. Diane gave us a bag with perhaps 15 books she’d published in it, to give to Mary, along with her love and regards. Early on the morning of June 24th, 2017––I remember it because it was St. John’s Day, and the St. Johnswort was in bloom all around––we set out in my friend’s green Tacoma to meet Mary Korte.

That day was a true high point in my life. I remember everything about it; I’ve written about it extensively in my dissertation (titled Pierce and Pine: Diane di Prima, Mary Norbert Korte and the Question of Matter and Spirit). Within 15 minutes of meeting Mary Korte, I felt like I could listen to her talk for days or weeks. Her place was a small, neat cabin on the bank of the Noyo River, surrounded by dense redwood forest. Never had I met someone who was so entirely a part of where she lived, who moved and breathed so seamlessly with her environment. Mary Catherine and I had a slew of questions for her, and our conversation spooled out beautifully over the course of the afternoon, into the evening, into the night. Darkness found us sitting in Mary Korte’s cabin, smoking her cigarettes and grass while she read us poems by headlamp (since her electricity comes from a generator, she conserves energy by not using lights after dark). We, in turn, showed her the poems she’d written in response to McClure’s Ghost Tantras, which she hadn’t seen since she wrote them in 1966. We read her the letter that Jack Spicer wrote to her in August of 1965, just days before his death––the last letter he wrote in his life. A sacred bond was formed among all of us, and I knew, as I had known upon my first encounter with Diane di Prima, that the underappreciated genius Mary Korte would be with me on my doctoral journey going forward.

(Mary sent us back to San Francisco with several ounces of what she called “Hail Mary Assassin Weed” for Diane and Shep, wrapped up in a colorful plaid cloth. This was very high-quality grass that she had grown herself in her small garden plot. Marijuana had been legal in California only for a few months at that point, and I admit it was strange for me––a native Californian used to furtively hiding my stash in my car––to drive for hours with such a huge amount of stuff without a care. We gave the fragrant package to Diane and Shep, who were thrilled, although I’m not sure if they ever smoked it.)

I set about learning everything I could about Mary Korte: I read her books, read William Everson’s writing about her in his book Archetype West: The Pacific Coast as a Literary Region, and called her on the phone to continue the conversation about her life. I determined that I would write about both her and Diane for my dissertation and set about tracing the connections and divergences between them as writers. In August of 2017, Mary Catherine and I drove up to Rochester to spend some time with Mary Korte’s archived papers at the Rare Books, Special Collections and Preservation (RBSCP) at the University of Rochester. I felt like a detective on a mission to piece together an untold story, one that expanded and expanded the more I searched. Mary had been a Catholic nun for 17 years, and that fact seemed to be the main thing anyone knew about her. But she had also taught extensively on the Pomo Indian Reservation, homesteaded in Irmulco, and been instrumental in some of the biggest initiatives to save old-growth redwood forests in Mendocino county. My own father had known Mary Korte in Santa Cruz in the early 1970s, when she regularly sat in on a poetry class he was taking with William Everson as a student at the university. As with Diane di Prima, each story of Mary’s presence and impact became something like a signal, a glowing Hansel-and-Gretel breadcrumb to follow onward.

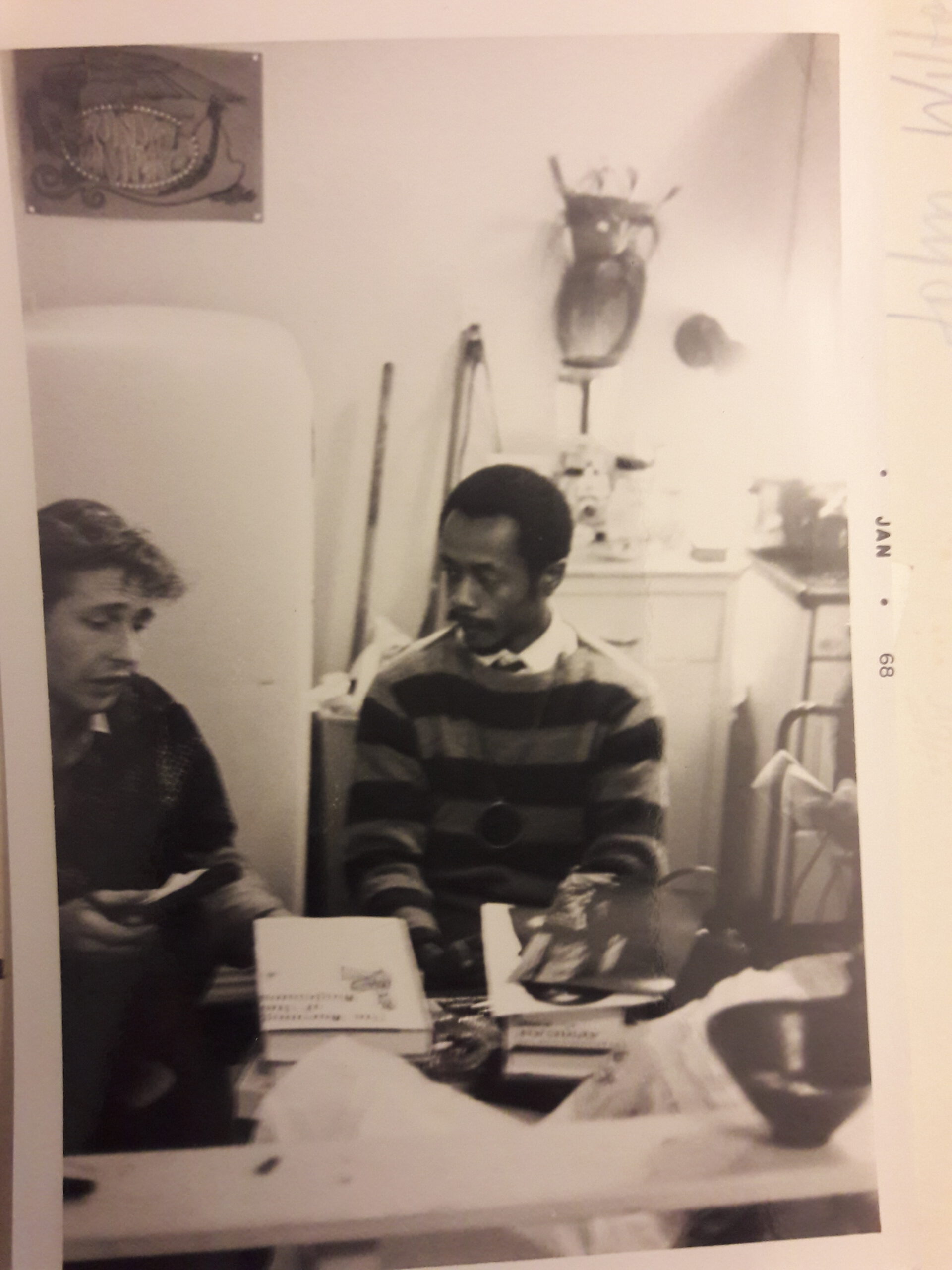

The glowing breadcrumbs kept appearing. The following winter, I visited Diane in the Center for Jewish Living, a nursing home about a mile from her house where she’s currently living. I spoke to Diane on that visit about my desire to become a mother, and also about my misgivings: the world was such a fraught and frightening place, it seemed, and was it really ethical to add another human being to it? She told me that if I thought I really wanted to have a child, I would have to shift my thinking. Rather than live in fear about the state of the world, she said, commit yourself to changing the world. Identify what needs to change, and work every day to change it, so that your children see the impact of what you’re doing. I thought of Diane’s Revolutionary Letters, the way they model living a life committed to revolution. I thought of Mary’s tireless, decades-long commitment to protecting old growth redwoods in California. Later that day, I went to Diane and Shep’s house to look for an image that might suit the cover of Diane’s Spring and Autumn Annals, which City Lights was slated to publish. As I looked through boxes of photos on the brick fireplace, I came across a black-and-white photo of David Henderson from 1968. I had known David for years, but never knew that he knew Diane, or that Diane had published his first book, Felix of the Silent Forest. Another crumb on the trail illuminated.

I continued to pay attention to the signals, and the trails I was following began to merge. The notes and conversations I’d had with Diane about Shelley and Prometheus Unbound grew into a chapbook for Series VIII of Lost and Found. I made two more extended trips to Irmulco to meet with Mary Korte and record more of her remarkable life stories. Mary Catherine edited “a strange gift”: Mary Norbert Korte’s Response to Michael McClure’s Ghost Tantras, the first book of Mary’s poems to be published in almost 30 years, also for Series VIII.

In the spring of 2019, I was invited to contribute to Ugly Duckling Presse’s 2020 Pamphlet Series. Recalling the moment discovering David Henderson’s photo in Diane’s house, I decided to use the opportunity to focus on the marvelous David Henderson-Diane di Prima connection. I had always found David a refreshing and enlightening poet and thinker, full of insights that pop open like outrageous spring flowers. We began to talk somewhat regularly on the phone, and then in person in a Manhattan coffee shop. David’s Felix of the Silent Forest was published by Diane’s Poets Press in 1967, the same season that Mary Korte’s first book, Hymn to the Gentle Sun, came out with Oyez Press. I zeroed in on the coincidence of these poets’ first books––poets who also occupied the vital roles of labor organizer and Society of Umbra founder (Henderson), on the one hand, and Catholic nun (Korte), on the other—coming out in the same year, a year rife with major societal transformations. I decided to focus on these two books for the pamphlet project.

In the summer of 2019, heavily pregnant and endeavoring to follow Diane’s sage advice to do the necessary work to change the world, I took another trip up to Rochester to peruse Mary’s papers at the University of Rochester’s RBSCP. I found folders full of her correspondence with the Friends of the Noyo, the group she founded to aid in a legal battle to protect 426 acres of old-growth redwood forest from being logged by corporate logging operations. There was correspondence with attorneys and with CalFire (the state agency that deals with forest management on public and private lands); there were minutes from legal hearings in which Korte took Georgia Pacific lumber company to court as a plaintiff, trying to stop them from logging the forest at the headwaters of the Noyo river, where she lives. I had many long conversations on the phone with Mary, in which she told me the story of her 30 year-long battle to save that particular area of the California redwoods. I gathered the archival research and Mary’s story into a little chapbook titled Into the Long Long Time: How Mary Korte Saved the Redwoods. My friend Essye Klempner printed it on the risograph printer at the Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop in Hell’s Kitchen and published it under her imprint, Ink Cap Press. The book features two previously unpublished poems by Mary, “Into the Long Long Time” and “Noyo Redwoods Jubilee.” (Mary won the battle to protect the trees, by the way; the forest at the headwaters of the Noyo is now the Noyo Redwoods Preserve, owned by the Mendocino Land Trust and designated as a wilderness area in perpetuity).

In August of 2019, my son Benny was born. I used some of the otherworldly, timeless energy of new motherhood to keep studying the moment that Henderson’s and Korte’s first books came out, and to read the books themselves. In October, Benny and I went down to the city to visit with David in the West Village, to talk to him more about his life and work in the 1960s. In the midst of all of the hustle and bustle, the crowded sidewalks, a sleeping infant strapped to my chest, a slew of questions to ask David, a moment of pure peace emerged: David showed me how to throw the I Ching using dimes. I carefully drew the lines of the hexagram we came up with together in a notebook on the tiny table that stood between us. Something about that moment felt germane with the energy of Diane di Prima’s world in the the 1950s and 60s: allowing all of the activity around oneself to happen, the comings and goings of poets and dancers, the needs of babies, one’s own needs, and in the midst of it all, beautiful moments of spiritual clarity. I looked up the hexagram that David and I threw that evening: it was 小過 (xiǎo guò) or “small surpassing”. The message of this hexagram is that one should attend to the small or minor aspects of one’s life with steadfast devotion.

My conversations with Henderson and Korte, and my research into the small press culture that their first books came out of, grew into The First Books of David Henderson and Mary Korte: A Research, which was published by UDP in July of this year. It’s one of numerous pieces that will soon come together in my dissertation, which I’m tentatively titling Pierce and Pine. Those are the names of the streets that intersect at St. Rose, the convent in San Francisco where Mary lived for many years, and which are not too far from the streets that both di Prima and Henderson lived on. In my mind, Diane is “pierce”: cutting through all the layers of ego and fear and getting straight to the truth. And Mary is “pine”: longing, steadfastly devoted. And the tree, of course, in all of its many glorious forms: Douglass fir, rock pine, juniper, ponderosa and redwood.

This essay was written shortly before Diane di Prima passed away in October 2020. For Iris’s writing on the meaning and impact of Diane’s legacy, in the wake of her passing, please read her beautiful reflections here: Remembering Diane di Prima, Diane di Prima’s Guidebook to Revolution, and On Diane di Prima.