Rhea Tepp

The archive has always been a place of great discomfort for me. Usually I have seen it presented with a capital “A”—a place of hierarchy (filled with items deemed “worthy” of preservation), a colonized space, a space of trauma, untouched by the passage of time. My mother is neurodivergent. When her body is placed in an institution, she is categorized, pathologized as having “multiple personality disorder.” I used to keep an archive she created of the names, identities, and lives contained within her. I kept these as secrets, aware that revealing the histories to the social workers, doctors, or police officers involved in our daily navigation of systems could have serious consequences on our ability to have regular visits, on her ability to be seen and unseen.

There are the archives of psychologists and psychiatrists with diagnoses of her condition, medication prescriptions, emergency room visits. There are legal archives of evidence that justify the reasons she was deemed “unfit”. I am not allowed to see those, or at least, was not, and have chosen to forget that I can have access to them now if I so desire. She has been tagged and untagged, placed in categorical boxes and zapped by machines in order to “correct” certain behaviors. She frequently describes her mood to doctors as “neutral” in order to avoid dangerous labels. Labels lead to consequences. She tells me in private that she exists in a state of purgatory, a transitional space. A space where the labels brought upon during existence have a chance to be extracted and purified.

Growing up I spent a lot of time listening, keeping thoughts to my self and in my journal. Zines became an important discovery to locate my voice. Controlling the production and distribution of my ideas, connecting and sharing with communities of like-minded individuals felt safe and exhilarating. At the same time, zines opened me up to an awareness of a lifetime of un-learning ahead of me. I respected the anonymity many authors chose to retain in their work, particularly in zines containing vulnerable content by marginalized voices. Many zine creators value accessibility over profit and the ethical tensions that arise when zinesters talk about digitizing work has paved the way for necessary conversations about why and how we archive our stories.

The VHS Archives Working Group is a loose alliance of academics in scholars from various disciplines, librarians, activists, artists, and activists. It was initiated in the spring of 2017 by Alexandra Juhasz, Professor of Media Studies at Brooklyn College with the goal of “discussing questions, concerns and best practices about the use, preservation, digitization, and research of VHS collections currently held by organizations, scholars, artists, and activists.” The following is a description of the second meeting I attended, on May 2, 2018, which centered around presentations by two members of the working group: Helena Shaskevich and Kate Roberts:

Valie Export sits in a seemingly empty space with the exception of a chair on which she sits, a bowl in her lap containing what appears to be milk and a blown-up photograph of two young children behind her. For just under ten minutes time, a single camera focuses on Export’s hands as she cuts away at her cuticles and nearby skin with a rusty box cutter. Her hair is down, slightly tussled. She is dressed in a black sweater and blue jeans and there is a somber glaze over her eyes that might be a scowl at the viewer. The sounds we hear are industrial, repetitive, like a pair of heels inside of an old dryer.

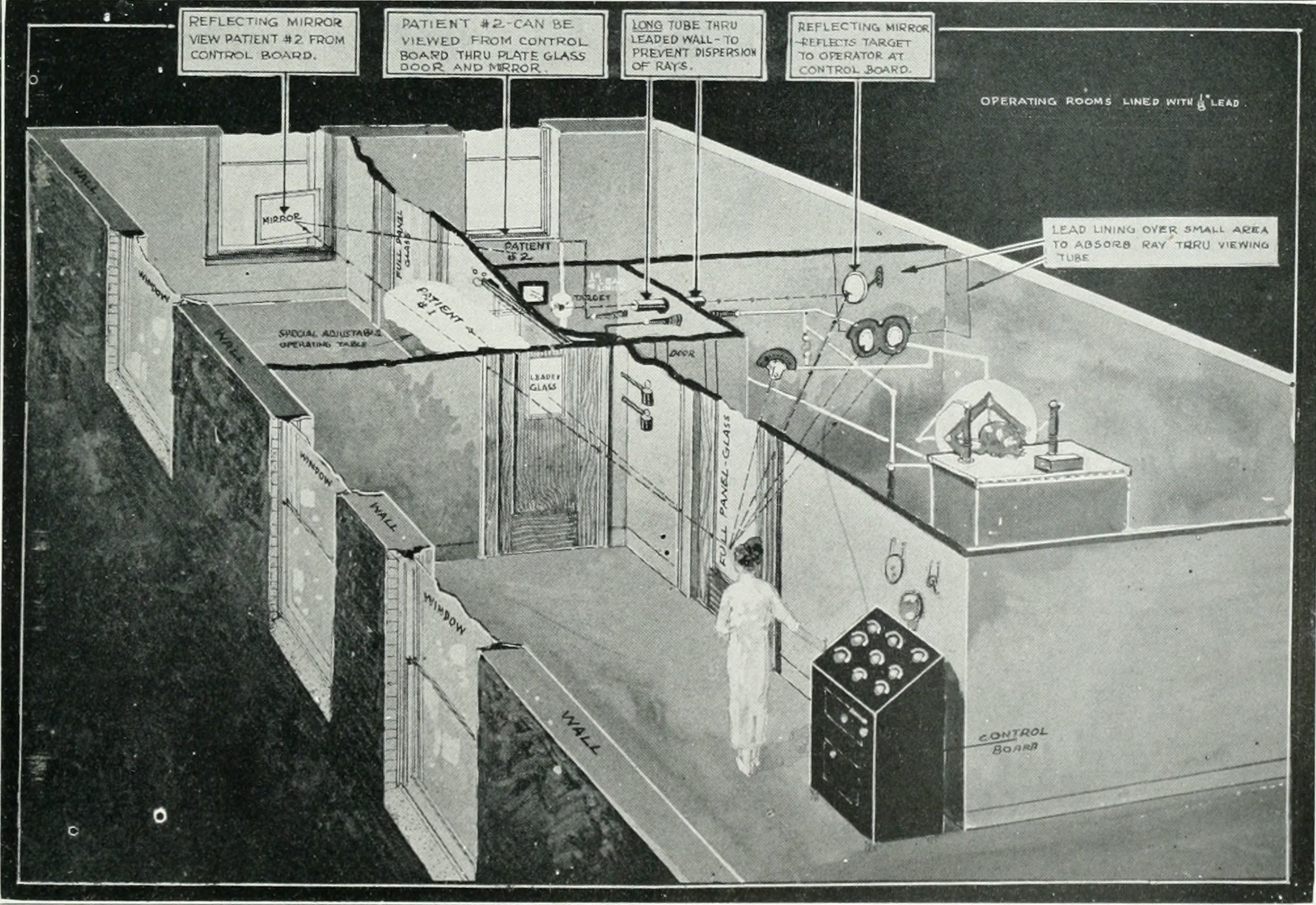

Helena Shaskevich, a doctoral student in the Art History program at The Graduate Center, presented a work in progress talk to the group, exploring her research of 1970s feminist media and medical landscapes. Before screening two videos, Helena shared with us a historical timeline of events to explore the intersections of different kinds of looking and knowing within media, health care activism and self-help movements.

The timeline of events included:

1960s: the growing use of fetal ultrasound

1967: video utilized by the everyday consumer leading to a reorientation of private (personal, family) life around TV and of public political life around televised moments

1970s: the beginnings of biotech

1972: pornography enters mainstream

1973: Roe vs. Wade

1978: the test tube baby

Helena encouraged us to think about several ideas before the screenings: the psychological state of narcissism in film, how the appropriation of Wonder Woman in Ms. Magazine became a trope, fragmentation/disruption when looking at the self as live feedback, and care/fragmentation appropriated through neoliberalism as a constant surveillance of the body/self. After these compelling and debatable ideas, we watched two videos. The first was from 1973, Valie Export’s ……remote………remote. I was not the only one who felt a bit squirmy and looked away during the moments of cutting and felt relief as we watched the artist dip tender digits into a bowl of milk and into her mouth. I thought about these moments in relation to control—the positional role of the viewer, the camera’s gaze, and how the artist’s gaze looking back at us influenced the relationship to self, body and surveillance of the other.

The second video we watched was from 1974, Lisa Steele’s Birthday Suit with Scars and Defects. The artist stands nude in another seemingly vacant space, on her birthday, first across the room from the camera, then close, as incidents resulting in scars are recounted chronologically. Steele spends several moments caressing each scar before and after the report of date, age and circumstance of occurrence. Anne Matsuuchi mentioned in our group notes that this contained no narrative, in the manner of an autopsy report.

The second presenter, Kat Roberts, a recent graduate of the MALS program in the Fashion Studies track, showed several video clips related to fashion as a means of constructing identity and objects as vessels of memory. The first two clips were held in conversation with one another: LA Fashion Sense (2017) by Deniz Karagulle and Topless by Carol Perlman (year unknown). Kat observed that the first clip was used to demonstrate the identity of the subject as told through fashion choices whereas the second clip was an example of fashion used as a shield. We considered the question: What is the trajectory of self-representation? Kat shared some insights about the modes of production and labor involved in creating textiles. She noted, modern clothing is not made to last and on average worn only 5 or 6 times. Kat suggested that social media plays a part in this shortened lifespan as many people are afraid of being seen in the same outfit too many times in photos. She spoke about her interest in denim as a gateway to experimentation. These two seemingly very different clips began to converge in my mind as Kat provided historical context and analysis of the fashion industry.

The third video clip was a series of personal interviews/oral histories entitled In Pursuit of Beauty: Imagining Closets in Newark and Beyond, produced in conjunction with a current exhibition up at the Newark Museum by the artist Deborah Harvest. Several one-on-one interviews were compiled together, each subject showing and sharing stories about an item of clothing that meant something to them (or in some cases, seemingly did not hold special meaning). Through these stories we explored clothing as an archive, as a sacred history, and the emotional attachment to objects. The setting of these interviews was casual, in living rooms and bedrooms, presumably belonging to the interview subjects.

As someone who is entering an academic space for the first time in over a decade (and who never really felt comfortable in similar spaces to begin with), in the working group, I have observed nothing but respect, acceptance, and a desire to meet people where they are at. I’ve enjoyed the group’s format of screening multiple video clips and allowing them to be in conversation with one another, as led by each presenter. I may not have much formal experience in a given area of study, but I still feel comfortable exploring the questions posed and ideas presented at my own pace. Through this week’s narratives of clothing, childhood physical scars and the cutting away of dead skin, our working group explored attachments to memory within selected artists’ work. I find that the zines I create are important personal archives that allow me to play with my own relationship to and transformation of memory. I used to create zines only for myself, until I realized the significance of a community that values the experiences of sharing works in progress—much like our VHS Archives Working Group does now.

Additional reading materials offered by Helena Shaskevich:

Rosalind Krauss, “Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism.” (1976),October Vol. 1, 1996. (50-64)

Beatriz Preciado’s “Pharmaco-pornographic Politics: Towards a New Gender Ecology” Parallax 14:1, 2008. (105-117)