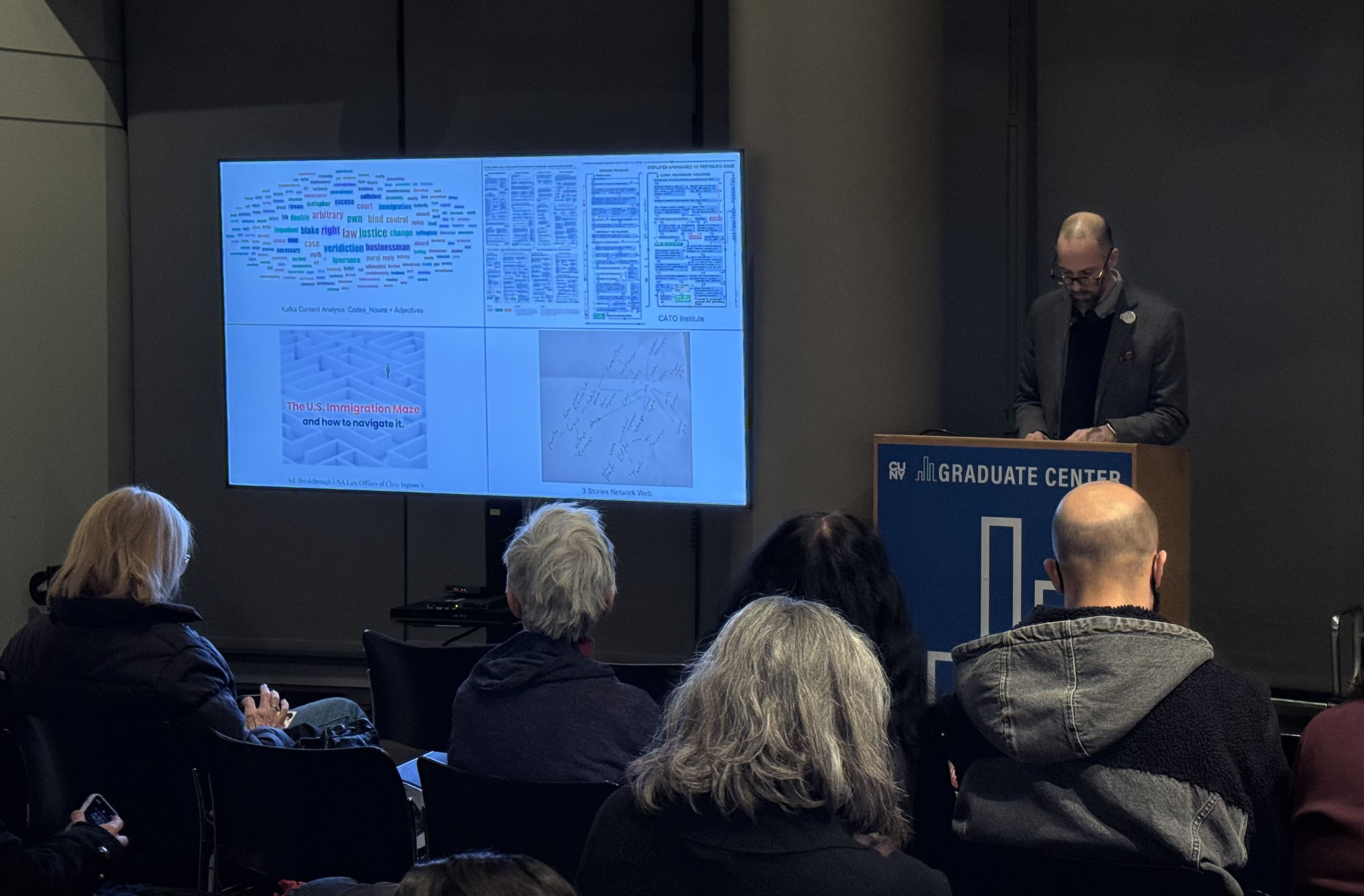

This essay by Jason M. Leggett is published on the occasion of “A Report to an Academy”: Student Responses to Kafka as part of the Kafka in New York symposium held on December 5, 2024. Graduate students from the CUNY Graduate Center and SUNY-New Paltz were invited to respond to the themes and materials in the Morgan Library & Museum’s Kafka in New York exhibition in new and subversive ways.

Beauty plus pity – that is the closest we can get to a definition of art…but I want to suggest that since art and thought, manner and matter, are inseparable, there must be something of the same thing about the structure of the story, too.”

Vladimir Nabokov, “The Metamorphosis,” (1915).[2]

I have known Davie[3] for 15 years and on more than one occasion, he has saved my life. On a cold Friday morning in Manhattan, he wandered around my small studio apartment while we prepared for the interview. He examined the paintings on the wall, took books off the bookshelf, and maintained a running commentary that weaved in cultural references from his home country, Guyana, philosophy from India, politics from Great Britain, and the rules[4] they imparted on him in school, as well as scientific concepts he was particularly fond of, usually involving nature or physics. He had told me this story before, but I wanted to get his thoughts on a legal term[5] I was wrestling with, sovereignty,[6]and so we meandered a bit before he recounted his detention[7] in Toronto. He said that he had always seen himself as an international man, like James Bond, and that he would be able to make it anywhere he found himself. When he was a child in British Guyana, he was often in charge of any group he wandered into, even though he was often the youngest. He said that he came to the United States as a teenager at the tail end of the migrations following the civil strife of regime change for three decades. He said that in the village where his family was from the social bonds were being broken down. He told me Indian Guyanese were being excluded from political and economic opportunities because of allegations of communism. Like many others he saw the United States as a dream,[8] where he could make a life for himself and that in Guyana there was nothing for him.

He described being “smooshed[9]” into a small cargo hold that had been rigged behind the back seat of a small pickup truck. My dad had a similar truck when I was a child, so I knew the kind of alterations he was referring to. There are two-fold out, pop up, seats behind the driver and passenger seats. They had modified a holding chamber under the truck that extended a few feet into the area of the truck bed. I could not help but think of a coffin when he described how little air[10] there was, which was not his first time smuggled into such tight spaces, and how hot he must have got from time to time. He could hear two border agents[11] over the classic rock playing on the radio, as they progressed into the U.S. from Canada, and he said he tried to be as still, and as quiet, as an “animal[12] in the jungle avoiding the hypnotic music of the charmer and his snake;” He was not entirely certain his bribe[13] would “pay out.”[14]

Davie’s transformation[15] from a young “James Bond,” he often repeated, into a smuggled animal,[16] who did not know how to “speak the streets of NYC,”[17] and then into a diligent worker,[18] and then back to a carefree, wandering spirit[19] but forever altered being, is very common among the migrants I have worked with or interviewed.[20]

The first time Davie saved my life was about two years after I had wandered to Brooklyn from Seattle, a 2,000-mile odyssey, and a few short months after I had graduated from law school, not long after The Great Recession.[21] In my spare time, I had been working on a socio-legal study of a man the New York Times[22] called Luis, who was “medically repatriated” against a federal court order,[23] in West Palm Beach, Florida. Davie had supported this research financially and even helped secure two suits[24] for me, from a Syrian merchant he knew in Chelsea, for my trip to Florida to observe the false imprisonment lawsuit[25] brought by his legal guardian, an attorney, and his “cousin” while under the care of his elderly mother in Guatemala.[26] I graduated in May and despite my best efforts had run out of money by October.[27] I was unable to pay for my room[28] in my shared apartment and was at that moment, displaced (or unhoused). Davie offered me a sleeping bag on the concrete floor of a basement[29] in the Bronx where he and his brother also slept. In exchange, I would work with him renovating high-end apartments in Manhattan and Brooklyn. The first time I saw a cockroach crawl near my head as I tried to sleep, I thought of Kafka.[30] I continued to work on my study of Luis, in the evenings, while Davie, and his brother, watched the BBC and the Discovery Channel in the dimly lit basement, for many months.

Luis was reported to have said that the reason he smuggled himself into the United States through the Texas border, made his way through Louisiana, and wandered into Indiantown, Florida was that he “wanted things[31]” and that God had punished him for these wants.[32] The story Luis and his mother told me, after I spent two weeks trekking through Guatemala, against the warnings of the U.S. State Department due to cartel wars and political turmoil, into the misty Highlands,[33] was more complicated. There was a sickness spreading among children, which I witnessed, and it had afflicted his young daughter. There were rumors it was related to unwanted sexual activity from outsiders but who could confirm such details? Even a radical journalist I had met on my journey suspected, but could not prove, and she also was more than anxious to keep herself free from harm.[34] Other men had secured medicines in the United States, but they were expensive, meaning he would have to work first. The men the Times reported about, those who “wanted things” never made it far beyond the border, according to many from the village. As an indigent Mayan, largely through routine political and legal processes, he and other Maya, are routinely excluded from the benefits of citizenship[35], and have been the targets of mass homicide. In my field research over the course of a month of interviews and observations in Guatemala in 2011, Mayans are separated from the larger cities and towns in small, rural villages. In Luis’ case his village is atop the Highlands cratered in the mountain and is nearly inaccessible.[36] Political candidates make no effort to engage Mayans in the electoral process, there is no health care or education access, and the police do not even bother to investigate the rape or murder of Mayan women. When I repeatedly asked Mayan migrants why they take the great risk to trek across dangerous borders into the United States, most expressed they simply had no other choice. That journey and the risks associated with undocumented entry were less than those of staying put.

In the United States Luis was undocumented. In Guatemala he is excluded and therefore stateless.[37] Mayans, like the undocumented in the U.S., while literally connected to the soil historically, are without a state[38] and are not treated as full citizens in any jurisdiction nor protected by its rules. The belief in individual rights and thus sovereign law as voluntary[39] for the majority but compulsory for the minority, yet seemingly acquiesced[40] to, applies to this case as well. Within both the repressive legal order of Guatemala, and the so-called liberal legal order of Florida, the outcome was the same.[41] In these cases, Luis, and other undocumented humans, are denied access to the bundle of rights attached to recognized citizenship.[42] They exist in a double-bind, an “oppressive air” as Kafka says repeatedly: They are excluded from the political system and yet subject to the laws of the jurisdiction.[43]

The discourse of the deserving immigrant against the undeserving[44] “illegal[45]” was repeated daily in my interviews in Florida. Nearly every citizen I spoke with described a political position against undocumented immigrants who “snuck” into the country but admitted they would employ them because of the cheap labor costs. In an all-undocumented section outside of town, much like the villages I saw in Guatemala, this contradiction appears evident.[46]There were no medical facilities, no schools, and housing was minimal. The only children who were educated were those who found sanctuary in Catholic Charities. When I interviewed those children, their stories and memories were heartbreaking. I was given a book that had documented similar traumas in the past and the author repeated the discourse of the optimistic belief in the liberal legal order to resolve the inherent contradiction of individual rights.[47] The belief in individualism[48] built upon faith in due process once again blurs the lines between sovereign law as command, compact, or counsel.[49]

What do these three stories have in common under the law and sovereignty of the state? We were all transformed by and through U.S. immigration laws and politics of policy, a labyrinth[50] of draconian,[51] arbitrary and capricious procedures,[52] malleable rules,[53] and wild interpretations based on intentional disinformation and hegemony. One represents the generational trials of indentured servitude and British colonialism and the transformations one must take in America, I represent the inheritances of the colonial settlers wrestling within the confines of society and armed with logic’s law, as if trapped in a castle, forever subservient to its decrees, and Luis represents the projections of our futures.

The divisions of our “selves” and the divisions of “justice” are important to me. In my research, I have found that everyday commonsense postulates an undivided, universal justice;[54] This is also the story that humanitarians and liberal law tells us about law.[55] But that is not the end of the story. Kafka does not get something quite right. As Michael McCann observed in his study of resistances for Women’s equal rights in the workplace, humans as active, social agents, up against a dominating force, within a social field of unequal relations, ever producing hegemonic knowledge, different knowledges are formed in this resistance, and distributed, unequally, yet ever present.[56] Where there is domination, there is resistance; where there is resistance, there is domination, and on and on it goes.[57] This is the multiple co-constitution of law and our parts are not set in stone. We all choose, even if within a field of unequal social relations.[58]What seems like a contradiction is merely a commonly accepted concept in law that something can be necessary, but not sufficient. Resistance in the face of injustice is necessary, but it is not sufficient to eradicate domination.[59]

Davie told me many stories of other migrants he knew, how they started, and where they ended up. He concluded his thoughts with, “there is a lot of fear within immigrant communities and the term illegal immigrant. They think they are treated unfairly and more sympathetic toward those who want to make a place for themselves. No place belongs to me. No matter what happens, I stay on course.” Davie perceives sovereignty through the British parliamentary system and through his religious beliefs. “We are all bound to the God of Abraham,” he explained. “The Queen and the King, you and me, we are all part of that same system.” This explanation is like that of the civic religion school of thought. In this narrative sovereignty is rooted in the feudal notion of the subject. However, the moral obligations of the compact are formed, not through voluntary choice, but through shared values among the community.[60] When we see that we are all part of the same system, we can begin to co-constitute new narratives for a more equitable order. Despite the story thatbefore the law would imagine for us, we all experience moments of being up against the law, and when we need them, lawyers use with the law, as if in a game, for in the end, that is all these trials really are.[61] Understanding that all three stories are true, is also how to bring matter and manner into unity, in the art of legal storytelling. It is only then that we can break free of the service the law requires and yet it is “something [we] seem not yet to be aware of.”[62]

In closing, after I passed the Bar Exam, I made the decision to walk away from the service of law and to instead become a critique of its absurdity and to try to organize against its arbitrary and capricious excesses.[63] Not long after, I survived a violent assault and went through brain rehabilitation and trauma therapy related to post-concussion syndrome, traumatic brain injury, and post-traumatic stress disorder. These were the same treatments denied to Luis, an eerie coincidence that rings with Kafkaesque dramatic intrigue. As I awoke in the hospital, there was Davie, grinning a Cheshire smile, and ready to tell me more stories. That was the second time he saved my life. Our interconnectedness is what allows for the work on immigration law, policy, and advocacy to continue. Two of my mentors from the University of Washington first introduced me to this kind of resistance based socio-legal scholarship, set me on my on my journey, and I quote both here to conclude in gratitude:

I found ordinary people had rather more “access” to the law, broadly understood, than either Kafka suggested, or I anticipated. Moreover, the stories that I heard from activists did not confirm many critical analysts’ arguments that law works primarily to mystify and legitimate domination in our society.[64]

A second major question is that of the nature of Law – whether it is liberator or repressor. It should now be clear why it is both in one sense and neither in another. My argument is that Law as an activity, returned to the world, must repeat the fundamental relationships of liberalism…because the law upholds and reinforces the order/power relationships it appears to be repressive. But, by the same token, the Law upholds and reinforces the freedom/rights relationships, and may thus be viewed as liberating…but, to repeat, there is no such thing as “The Law.”[65]

Author

[1] The call for proposals asked for “Innovation” and I drew from the following sources to construct this experimental paper: 1) Katherine McKittrick. “Footnotes (Books and Papers Scattered about the floor)” in Dear Science and other stories. (Duke University Press, 2021). p.34. Specifically, I strove to be in conversation with McKittrick about footnotes and resistances, from my own positionality, and that I agree that referencing is hard (and often subject to unnecessary judgment): “we share our lessons of unknowing ourselves and, in this, refuse what they want us to be; we risk reading what we cannot bear and what we love too much and then we let it go, revise, and read it again.” This essay is part of a larger study of legal consciousness, or the politics of rights talk, and that project owes a debt to Critical Race Theory, and in particular, the work of Charles Lawrence as he articulates the struggle against injustice as the Word. 2) Charles R. Lawrence, III, “The Word and the River: Pedagogy as Scholarship as Struggle,” In: Crenshaw, K., Gotanda, N., Peller, G., Thomas, K. (eds). Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings That Formed the Movement. (New York, The New Press, 1995). p. 336. “The Word is praxis, not just in the more obvious ways the thoughtful work of a scholar provides strategy or frames new conceptual arguments for the activist lawyer or community organizer, but in the ongoing work of the scholar as teacher.” In my studies comparing everyday language, metaphors, and narratives of marginalized populations in contrast to that of judges, I have discovered much emanates from footnotes. 3). The Supreme Court Justices often use footnotes, sometimes taking up more of the page than the opinion text, to articulate a variety of positions; for example, see. Peter C. Hoffer’s The Supreme Court Footnote: a surprising history. (New York University Press, 2024). What else might we find in the shadows of forgotten metaphors? 4) Gregory Bateson. A Sacred Unity. Harper Collins, 1991) pp.224-225. “And again, there is a misquotation that is going the rounds today:

A man’s reach should exceed his grasp,

Or what’s a meta for?

I’m afraid this American generation has mostly forgotten “A Grammarian’s Funeral” with its strange combination of awe and contempt…I said I would reread “Metaphor” and tell you how that conference looks as I look back on it….” And how does this lead to a construction of legal poetics and a new metaphor based in an old cosmology? 5) Willam Blake. “The Human Abstract” in Poems, selected and introduced by Patti Smith. (Penguin Random House, 2007). P. 120.

“Pity would be no more

If we did not make somebody poor,

And Mercy no more could be

If all were as happy as we.

And mutual fear brings peace,

Till the selfish loves increase:

Then Cruelty knits a snare,

And spreads his baits with care.

He sits down with holy fears

And waters the ground with tears:

Then Humility takes its root

Underneath his foot.

Soon spreads the dismal shade

Of Mystery over his head,

And the Caterpillar and Fly,

Feed on the Mystery.

And it bears the fruit of Deceit,

Ruddy and sweet to eat,

And the Raven his nest has made

In its thickest shade.

[2] Vladimir Nabakov: Lectures on Literature. Edited by Fredson Bowers. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980). P. 251.

[3] Name has been changed to protect his identity; interviews conducted under IRB 2022-0052.

[4] Ostrom, E. (1986). An Agenda for the Study of Institutions. Public Choice, 48(1), 3–25. Davie is mostly referring to “authority rules that specify the set of actions assigned to a position at a particular node.” For example, he would describe when he was allowed to be free from the school master’s gaze. He often refers to this kind of gaze in avoiding immigration laws.

[5] Franz Kafka. (2009). The Castle. Translated by Anthea Bell. p. 25. “The letter was full of such terms, and even when something more personal was said, it was written from the same point of view…as the letter put it, he had been accepted into the Count’s service.”

[6] Michel Foucault. (1977) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. pp. 53-54. Foucault explains the historical structure of sovereignty and punishment as “We must regard the public execution, as it was still ritualized in the eighteenth century, as a political operation. It was logically inscribed in a system of punishment, in which the sovereign, directly or indirectly, demanded, decided and carried out punishments, in so far as it was he who, through the law, had been injured by the crime. In every offence there was a crimen majestatisand in the least criminal a potential regicide…he attacked the very principle of the sovereign prince.” It is this potential attack on sovereignty that Kafka’s K is so clueless about and his ignorance is what substantiates his indignation. There are at least three comparisons that can be made: 1) The shift from public spectacle to disciplinary power: This resonates with the shift in The Trial from a focus on public trials and executions to a more bureaucratic and hidden form of legal process; 2) The pervasiveness of surveillance and control: Foucault’s analysis of the panopticon and the internalization of discipline aligns with the constant feeling of being watched and judged in The Trial. And 3) The inscrutability of the law: Both Foucault and Kafka highlight the way the law can become a mysterious and impenetrable force that individuals struggle to understand or navigate.

[7] Franz Kafka. (2007). The Metamorphosis and The Trial. Borders Classics. Translated by David

Wyllie. p. 63. “It’s true that you’re under arrest, but that shouldn’t keep you from carrying out your job. And there shouldn’t be anything to stop you from carrying on with your usual life. In that case it’s not too bad, being under arrest.”

[8] Kafka, F. (2007). p.3. “It wasn’t a dream…what a strenuous career it is that I’ve chosen. Travelling day in and day out.”

[9] Id. p.29. “With his head and legs pulled in against him and his body pressed to the floor, he was forced to admit to himself that he could not stand all of this much longer.”

[10] Id. pp. 104, 160, 170. “But the air is almost impossible to breathe on days when there’s a lot of business, and that’s almost everyday…when you’re here for the second or third time you’ll hardly notice how oppressive the air is.” “The air was also quite oppressive.” “He was entirely cut off from the air….”

[11] Id. pp. 54, 222. “I want to see who is that in the next room.” “Two men came…’you’ve come for me then, have you?’”

[12] Id. p. 41. “Was he an animal if music could captivate him so?”

[13] Id. pp. 93, 118. “It’s even possible that they will pretend to be carrying on with the trial in the hope of receiving a large bribe, although I can tell you now that that will be quite in vain as I pay bribes to no one.” “I would make it well worth your while if you would let them go….’that’s all very possible what you are saying there,’ said the whip man, “only I’m not the sort of person you can bribe.”

[14] Eleanor Ostrom. (1986). An Agenda for the Study of Institutions. Public Choice, 48(1), 3–25. This usage of paying out is invoking “payoff rules that prescribe how benefits and costs are to be distributed to participants in positions of authority or submission.” Davie often refers to these rules when calculating the risks he takes everyday, avoiding legal entanglements.

[15] Kafka. (2007). p. 25. “…after Gregor’s transformation when his sister no longer had any particular reason to be shocked at his appearance….”

[16] Id. p. 11. “That was the voice of an animal.”

[17] Kafka. (2009). p. 78. “I have never spoken to any real officials here. It seems harder to achieve than I expected.”

[18] Id. pp. 9, 13. “We simply have to overcome it because of the business considerations.” “that I’m not stubborn and I like to do my job; being a commercial traveller is arduous but without travelling I couldn’t earn my living.”

[19] Id. pp. 55,108. “K paid hardly any attention to what they were saying…K was living in a free country, afterall, everywhere was at peace, all laws were decent and were upheld…” “It seemed to him that all his strength had returned to him at once, and to get a foretaste of freedom…he ran down the steps so fresh and in such long leaps that the contrast with his previous state nearly frightened him.”

[20] Ostrom. (1986). These roles and boundaries evoke “position rules that specify a set of positions and how many participants hold each position,” and “boundary rules that specify how participants are chosen to hold these positions and how participants leave these positions.” These types of rules are most similar to that of the “lottery” in immigration laws and have a big impact on the narratives migrants tell.

[21] Kafka. (2009). p. 85. “Whether or not any salary is paid…will be considered after a month’s service on probation.” I too took on speculative jobs as a “contract lawyer” or “consultant.”

[22] Deborah Sontag, NYTIMES. Immigrants Facing Deportation by U.S. Hospitals. August 3,

2008. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/03/us/03deport.html

[23] Kafka. (2007). pp. 173, 225. “The right to acquit people is a major privilege and our judges don’t have it, but they do have the right to free people from the indictment…it only takes an order from higher up to bring it back in force.” “In the end, they left K in a position that was far from the best of the ones they had tried so far.”

[24] Id. p. 59. “Ridiculous formalities…It’s got to be a black coat.”

[25] Id. p. 111. “He began to walk up and down the room between the window and the door, thus depriving Mrs. Grubach of the chance to leave, which she otherwise probably would have done.”

[26] Id. pp. 24, 35. 122. “Would Gregor’s elderly mother now have to go and earn money?” “Who, in this tired and overworked family, would have had time to give more attention to Gregor than was absolutely necessary?” “Uncle Karl was K.’s former guardian, and so K. was duty bound….”

[27] Kafka. (2009). p. 40. “K kept feeling that he had lost himself, or was further away in a strange land than anyone had ever been before, a distant country where even the air was unlike the air at home, where you are likely to stifle in the strangeness of it, yet such were its senseless lures that you could only go on, losing your way even more.”

[28] Id. p. 44. “It’s got to go, that’s the only way….”

[29] Id. p.201. “He practically lives with me so that he always knows what’s happening. You don’t always find such enthusiasm as that.”

[30] Kafka had suffered his own traumas that no doubt were on his mind’s writing eye.

[31] Id. pp. 36. “And although he could think of nothing that he would have wanted, he made plans of how he could get into the pantry, where he could take all the things he was entitled to….”

[32] Id. p. 36. “….the thought that they had been struck with a misfortune unlike anything experienced by anyone else they knew or were related to.”

[33] Kafka. (2009). pp.11. “…on the mountain everything rose into the air, free and light, or at least that is how it looked from here.”

[34] Kafka. (2007). p. 71. “I don’t want to make any pronouncements that might have serious implications.”

[35] Ostrom (1986). An Agenda for the Study of Institutions. Public Choice, 48(1), 3–25. Exclusionary rules can only be thought of as “information rules that authorize channels of communication among participants in positions and specify the language and form in which communication will take place” because before the information is processed, the participant cannot be imagined in the game, with the law, and is merely waiting to be assigned a name.

[36] Kafka. (2009). pp. 29. “By day the castle had seemed an easy plate to reach…had Barnabas led him along a way that climbed only imperceptibly? Where are we?”

[37] Id. p. 195. “Then they are not officially acknowledged employees, but they work under cover and are semi-official. They have neither rights nor duties….”

[38] Kafka, F. (2007). p. 87. “This organization even maintains a high-level judiciary along with its train of countless servants, scribes, policemen, and all the other assistance that it needs, perhaps even executioners and torturers – I’m not afraid of using those words.”

[39] Id. p. 54. “…he must to some extent have acknowledged their authority by doing so, but that didn’t seem important to him at the time.”

[40] Id. 97. “This little bastard won’t let me. And don’t you want to be set free?… No!”

[41] Id. 220. “The lie made into the rule of the world.”

[42] Id. “In front of the law there is a doorkeeper. A man from the countryside comes and asks for entry. But the doorkeeper says he can’t let him in the law right now.”

[43] Id. “But the air is almost impossible to breathe on days when there’s a lot of business, and that’s almost every day.”

[44] Talia Shiff (2020). Reconfiguring the Deserving Refugee: Cultural Categories of Worth and the Making of Refugee Policy. Law & Society Review, 54(1), 102–132.

[45] It is impossible for a human to be illegal as the illegality requires a criminal act (of which unauthorized entry into the U.S. is a misdemeanor) and a criminal, or criminally negligent, state of mind. To cross a border seeking asylum, itself a lawful process, cannot be transformed into a criminal act without undermining the entirety of the rule of law.

[46] Kafka. (2007). p. 169. “I think you are contradicting yourself…you remarked earlier that the court cannot be approached with reasoned proofs, you later restricted this to the open court, and now you go so far as to say that an innocent man needs no assistance in court. That entails a contradiction.”

[47] Id. 91. “Do you really believe you will be able to make things better?”

[48] William Haltom and Michael McCann. Distorting the Law: Politics, Media, and the Litigation Crisis. (University of Chicago Press, 2004). P. 304. “It has become commonplace to think of ‘individual responsibility’ as a hegemonic ideology in the United States that generally supports, but because indeterminate, also provides resources for contesting dominant relations.”

[49] William Blackstone. Blackstone’s Commentaries Abridged. Ninth Edition.

(Chicago: Callaghan and Company, 1915), 4. Check page number

[50] Ingram, Chris (n.d.) LinkedIn Advertisement Post: The U.S. Immigration Maze and How to Navigate It. https://www.linkedin.com/posts/eb1specialists_workvisa-usvisa-greencard-activity-7238879874600329217-g5KB

[51] I learned as a legal researcher and writer, the surest way to get the attention of a judge is to refer to laws as draconian. For example, see https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/enhanced_scrutiny_test

[52] For example, see https://ballotpedia.org/Arbitrary-or-capricious_test

[53] Melissa Weresh. (2014) ‘Stargate: Malleability as a Threshold Concept in Legal Education,’ 63(4) Journal of Legal Education 689.

[54] Jason M. Leggett (2023) From the bottom up: marginalised students’ narratives of constitutionalism at an urban community college in the United States, Jindal Global Law Review, 14(1) 77-97.

[55] Susan Silbey and Patricia Ewick. The Commonplace of Law. See also Linda Medcalf.

[56] Michael McCann. (1994). Rights at Work: Pay Equity Reform and the Politics of Legal Mobilization. (University of Chicago Press).

[57] Kafka. (2007). p. 173. “…the case gets passed to higher courts, gets passed back down to the lower courts and so on, backwards and forwards, sometimes faster, sometimes slower, to and fro…no documents get lost, the court forgets nothing.”

[58] Foucault. (1977). “Where there is domination, there is resistance.” The opposite of course is true is well, resistance creates new powers of domination.

[59] Kafka. (2009). p. 248. “And what kind of human being wouldn’t respect that? Well, someone like K. Someone who would set himself above everything, above the law….”

[60] Id. at p. 190. “No one has yet discovered the rules governing that change.”

[61] Lewis Carroll (2006). “Who Stole the Tarts,” in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. Bantam Classics.

[62] Kafka, F. (2007). p. 88. “I merely wanted to draw your attention, said the judge, to something you seem to not yet be aware of: you have robbed yourself of the advantage that a hearing of this sort always gives to someone who is under arrest.”

[63] Id. p. 218. “Above all, the free man is superior to the man who has to serve another. Now, the man really is free, he can go wherever he wants, the only thing forbidden to him is entry into the law and, what’s more, there’s only one man forbidding him to do so- the doorkeeper.”

[64] McCann (1994). p. ix.

[64] Linda Medcalf. (1978). Law and Identity: Lawyers, Native Americans, and Legal Practice. (Sage). pp. 126-127.