The Urban Politics of Climate Change: a conversation with Naomi Schiller

August 7, 2023

The vanguard of the climate struggle is not solely in areas we designate as “rural,” “remote” or “natural.” In fact, the popular assumption that it is—the myth of wilderness—might be part of our problem. The historian William Cronon argued this in his great essay, “The Trouble with Wilderness: Or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature,” which ends with this provocation: “If wildness can stop being (just) out there and start being (also) in here, if it can start being as humane as it is natural, then perhaps we can get on with the unending task of struggling to live rightly in the world—not just in the garden, not just in the wilderness, but in the home that encompasses them both.” The present work of Naomi Schiller, associate professor of anthropology at CUNY’s Brooklyn College and the Graduate Center, rises to meet Cronon’s challenge by focusing on her own neighborhood of the Lower East Side, Manhattan. I first heard about Professor Schiller’s work through the Center for the Humanities’ Mellon Seminar on Public Engagement and Collaborative Research for which we were both fellows in the “blue humanities.” This past semester, I had the privilege to sit down with Professor Schiller and learn more about her approach to climate activism, which blends academic scholarship with community organizing.

~~~

Eric Dean Wilson: What is the environmental humanities? That’s a question I’ve been thinking about all year. In a way, it’s an emerging field. But it’s also a return to old ways of knowing before the disciplines got separated.

Naomi Schiller: I’m not really quite sure! But I know I don’t want to be wedded to disciplines. I love anthropology, but I don’t want to spend my life trying to defend a certain understanding of what the field is or policing its boundaries. So I love the idea that environmental humanities could bring together people who are working on climate and environment and ecology and politics, broadly construed. That it could bring different perspectives.

I’m a cultural anthropologist, and anthropology straddles the humanities and social sciences. At Brooklyn College, we’re in the School of Natural and Behavioral Sciences, weirdly, and that was a result of a strategy to fund our labs and research. So am I a humanities scholar? I’m writing a book based on ethnographic and archival research about my neighborhood and the struggle over how we adapt to climate crisis. I made a short documentary film On the Line about food insecurity at the beginning of the pandemic. I’m finishing a handbook for organizers called Disruptive Engagement based on a participatory oral history project I co-facilitated with land use and housing organizers in New York City.

Your terrific book, After Cooling, is the kind of writing I aspire to do-–the ethnographic/ descriptive. You do it so well! You’re placing yourself in the writing, it’s layered, and it’s historical—that, to me, is the best of what the humanities can be. I don’t know what to call that, but I’m happy to have a home in something called “environmental humanities.” But I’ve never used that term.

EDW: For me, one of the challenges of climate-related work is the immensity of scale. It’s easy to become overwhelmed by trying to see the problem in its entirety. I find your work moving because it’s tangible and it’s rooted in place. For example, you frame the housing crisis in the Lower East Side of Manhattan as a “central nexus of climate politics.” Can you explain that connection in terms of your book project on the urban politics of climate change?

NS: (laughs) I hope so! The book is very much a work in progress. I’m still trying to figure out what it’s about. And I just finished a draft of one of the first pieces of it that I’ve been working on forever.

EDW: Congratulations!

NS: Well, I finished a draft of a piece.

EDW: That’s a huge accomplishment.

NS: Yeah, but I’m stuck right now. My head is still in this one little part of it. As you know, in trying to write a big project, you think, Is this piece the whole thing? Or is there more?

The starting place of my book project is this very local battle over a two- to two-and-a-half mile flood protection plan, the East Side Coastal Resiliency Project. It now has a price tag of about 1.45 billion dollars. And it ignited this firestorm of emotionally intense and fraught debate in the neighborhood about who gets to assume leadership, who gets to say what we should do here, and what the right approach is.

Residents in the Lower East Side view renderings of New York City’s plan to remake East River Park as part of the East Side Coastal Resiliency project, March 2018 (Naomi Schiller)

Part of what I’m interested in is how people come together. Climate change is often framed as this thing we all face together. That it’s going to bring together humanity because it’s something that will “affect us all.” Of course, there’s so much important critique of that statement. Climate change is not the first existential threat to many populations if you consider settler colonialism, slavery, genocide. Still, I wonder: How do we face this problem of climate catastrophe? Is there a “we”? How to even understand the problem?

So I’m trying to look at this very local battle, which, for some people who are pushing back against the proposed flood protection plan, didn’t begin as a fight about climate politics. It was a struggle against losing the green space that meant so much to them. There are many layers. I’m trying to pull apart the threads: What changes do we think we should make as a neighborhood and as a city? What needs to be changed? How do we build solidarity with one another in order to have this conversation? What do we gain and sacrifice by making the changes that we need to make? And, at least in this little piece, which is about efforts to build a coalition and the role of racism in the neighborhood and the city, I’ve come to understand what happens when we don’t understand the history of how we got here in a very material sense of the housing that was constructed along the East River. What’s the relationship between New York City public housing and these private condo cooperatives that were built in the 1950s by unions together with Robert Moses and the city, private housing that got state financing. What is the relationship between public housing and the private housing that’s right beside it?

Destruction of East River Park in front of East River Coop (left) and NYCHA’s Baruch Houses (right) (Naomi Schiller)

I live in a mostly white, mostly middle-class co-op along East River Park. The development where I live was begun in the 1950s by Jewish, socialist-leaning unionists who believed in cooperative models, and then the buildings were privatized in the 1990s. Over that period, as it turns out, the co-op boards were racially discriminating against people of color applying for housing. So I’m trying to think about this history of liberal New York and how changes in global capitalism shape the formation of this neighborhood over time and the shifting articulations of racism and antiracism. I’m looking at the neighborhood but my primary interlocutors are other white, middle-class people who live in privatized housing. How do they understand the politics that they’re engaging in, and why are the tools of liberal anti-racism insufficient to manage what we’re facing?

EDW: It reminds me of the struggles against toxic waste dumps in communities of color in California and Warren County, North Carolina in the 1980s. One of the huge lessons there was that people didn’t have to all agree on the same principles, necessarily. They didn’t have to oppose the waste management companies for the same reasons. What emerged was unlikely solidarity against a single, toxic project. That feels hopeful to me, and it feels like a lesson we’ve forgotten, especially on the left, where we feel like we have to begin by agreeing on everything first. Historically, that approach hasn’t been met with a lot of success.

NS: Yeah. Maybe people don’t have to understand all the history or share all the same principles; they just have to have their own reasons for being involved that dovetail in some way with other people’s concerns. But I think that some of what happened on the Lower East Side is that there was a tremendous lack of understanding about why different perspectives on the project emerged among people in leadership on opposing sides of this struggle over resiliency infrastructure.

After Sandy, there were five years of intense community engagement in which the city won some consensus about a design for the project. Then DeBlasio changed the plan in 2018, instead of cutting down 700 trees and building some berms, they’re going to cut down 1,000 trees and obliterate the park. The plan now is to use eight to ten feet of fill and build a new park on top. So the local leaders of color—not just the housing authority leaders but people who’ve been in the trenches leading community organizations—were angry because they had participated extensively in the design process. They were key actors in shaping the plan, and they were part of what allowed the proposal to gain the legitimacy it needed to get the funding for the project from the federal government through HUD. They were angry that the project had been changed.

Meanwhile, many of my middle-class white neighbors knew little about the project, and so the first time they found out about it was when DeBlasio changed the plan, and they were very angry about the total loss of the park. But the long-time leaders of the neighborhood who’ve been dealing with the city forever, who’ve been fighting to fund public housing, who’ve had all these relationships good and bad with city officials, elected officials, some of whom they’ve cultivated and have come out of their communities—they eventually said, “Fine. This is the best we’re going to get. This is the plan. We don’t want another Sandy.” The experience was different for many white, mostly middle-class people who lived next door, like me. Resilience is a class-shaped capacity. That doesn’t mean that everyone in public housing supports the resiliency plan and everyone in private housing is against it. Not at all! There is a lot more complexity.

Sandy was supposed to be a “wake-up call.” That’s what DeBlasio said. But it was a very different call for different populations in terms of the experience. So we live side by side—same coastline, same flood—but they’re really different experiences. And in fucked up ways the city leaders used the racism that shapes my neighborhood—the institutions, the built environment, the relationships—as a tool to advance the city’s project. To push their new plan ahead the city said, “See? We are redressing the history of environmental racism by building infrastructure that will protect NYCHA from flooding.”

Now, I think the city’s resiliency plan is deficient. It does not address the roots of racist planning or rising seas or environmental harm. It’s a very short term bandaid to try to keep things as they are when what we need is to change everything. But I understand why some people support it. I understand why some people see it as an investment in NYCHA. We need to understand how these decisions are shaped by past and present injustice. So I’m trying to sort this out and articulate how and why the liberal tools of anti-racism, which focus on individual kinds of bigotry and don’t have an analysis of how capitalism and racism are intermeshed, are just inadequate to understand our present climate crisis, build coalitions, and act.

EDW: It’s funny that DeBlasio said it was a “wake-up call.” It makes me think of how well Lee Zeldin fared in the fall election on Long Island, which was hit so badly by Sandy. There are many reasons for that, but on the tenth-year anniversary of Sandy, we see incredible support for this person who’s not going to do anything on climate. So even if, at one time, it was a wake-up call, now we’ve forgotten about it.

NS: I think it was more of a wake-up call for city officials. Flooding and sea-level rise was not on their agenda. One of the local leaders in my neighborhood often says something like: “We knew that greedy landlords were an enemy for a long time, but until Sandy we didn’t know that climate change was also an enemy.” For her, there was a turn toward seeing climate change as something that impacts working class people intensely. But when I hear her say that, I think, it’s the same enemy—the rapacious landlord! The capitalist! When we talk about the housing crisis, there’s a clear class analysis of who our enemy is. But when we talk about climate change, that often completely drops away. And that’s how the city built consensus for the first resiliency plan in my neighborhood: “We’re all in this together, we all face the same struggle, this water that’s coming for us all!” There was no analysis of the class politics in the neighborhood. Who benefits from this system of endless extraction and exploitation? Who’s responsible for this?

EDW: That’s why I think your focus on racial capitalism is particularly effective. It makes me think of the work of Ruth Wilson Gilmore who understands that this kind of class project is critical to undo for climate activism. It lives in our cities. It affects which neighborhoods are hotter because of access to shade. These things have decades-long, centuries-long effects in how they’re spatialized. It’s hard for people to see because that kind of violence is abstracted. It’s not one person hurting another person, which is, ironically, what we’re focused on in the city right now. We’re not focused on the indirect violence from government decisions, from what Professor Gilmore calls “organized abandonment.” What your project is doing is highlighting that less obvious violence and giving it a shape, so we can actually understand it.

Both your book and oral history projects have clear, public-facing outcomes: a handbook to help people make sense of what’s going on, to make sense of certain laws. Was that public-facing outcome clear to you from the outset, or was it something that grew organically out of these projects?

NS: I’m working with an artist-activist named Vanessa Thill to put together a handbook for anti-displacement organizers. Vanessa is active in many, many different struggles but focuses on housing a lot. She was facing the problem of artist-as-gentrifier and wanted to dig into that further, understand and address it. We first met when we were in a subcommittee of lower Manhattan DSA (Democratic Socialists of America), and we were trying to craft a housing platform for people running for city council races a while ago.

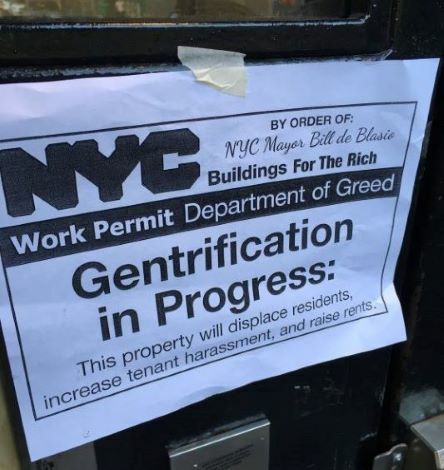

A spoof of an official work permit alerts neighbors to the displacement risks of the Inwood rezoning, 2018. (Northern Manhattan Not For Sale)

We started talking about the way that the city manages the public’s role in decision-making around land use changes. It’s siloed neighborhood by neighborhood, and it’s confusing. Lots of neighborhood organizers are engaged in similar struggles of trying to figure out what the public decision-making process is, how we understand it, what we do with it, and if it’s even worthwhile to engage it. So there’s this process—the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure, or ULURP—which takes seven months. In order to change a proposal for land use, it starts with a community-board discussion and ends up with a vote by the Mayor. It moves along from community board to the borough president’s office, to city planning, and to all of these other points. At almost every level there are public hearings where community members can testify. So there’s a big question: is it just an exercise that’s intended to exhaust communities and organizers? Or if not intended, exactly, it definitely has that effect. It takes up so much time and energy. We had to think a lot about what people and organized communities get out of community engagement procedures and if it is possible to navigate effectively, to engage and disrupt.

Residents and organizers in New York City protest the top-down nature of New York City’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure or ULURP (Naomi Schiller)

So Vanessa Thill and I developed a participatory oral history project to talk to housing and anti-displacement organizers around the city. We wanted to know how they got into this fight, how it fits in with their personal history, what they’ve learned, how they’ve managed burnout, how they collaborated or not with elected officials, how they saw the most useful way to engage the official public decision making processes, and what they would want new activists and organizers to understand. Each of these that I just listed came out of a series of meetings where we brought all of these people together, and with the Mellon funding from the Center for the Humanities’ Seminar on Public Engagement and Collaborative Research we were able to support people to do this work. Some Brooklyn College students and I did some training together about activist oral history as a method, and then we created a collective interview guide with questions. And then people paired up and interviewed each other, so rather than us interviewing everybody, the idea was that people would be getting to know each other and creating infrastructure among organizations. That was the aspiration.

We’re almost finished with the handbook we’ve created for organizers called Disruptive Engagement, which builds on the knowledge and advice we collected through our oral history project.

Forthcoming publication Disruptive Engagement: An Organizer’s Guide to Building Community Power for Justice in Land Use and Housing in New York City.

EDW: That sounds useful! Obviously, a crucial part of what you do is working with local communities like this. Do you find it challenging to navigate the ethics of those relationships? Do you have any advice for a researcher to ensure a more equitable exchange with a community they’re interested in learning about?

NS: Well, I think there’s no one answer. My first book, Channeling the State, was about Venezuela and community organizers and activists who were using community television as a way to get people involved in politics. My Venezuelan friends and interlocutors were always like, “What are you doing here? Go home and organize there. The problem is there.” Yes, I know! And I was trying to learn from what they were trying to build in Venezuela, how they were managing all the contradictions. So there’s a variety of reasons that I decided to focus on literally my own backyard, but one of the reasons was a question of ethics. Who am I going to be tied to for probably most of the rest of my life? I really want to be accountable, and I really want to be in it for the long term. That’s very difficult and painful as I’m trying to be critical. I hope I can contribute to what I’ve seen unfold around me, and I don’t really know how that’s going to go. When I got involved in organizing and documenting the struggle over the coastal resiliency project, I didn’t foresee that it would go in the direction that it has because of the limits of my own perspective at that time.

Channeling the State: Community Media and Popular Politics in Venezuela by Naomi Schiller.

So, in a way, one of the answers is to figure out how you can remain accountable over the long term. It’s probably better if it’s not something you can easily walk away from, even when you want to, unless you’re subject to harm, of course. People have joked to me, “Well, if you publish, you’re going to have to move.” (Laughs.) And it’s really different to encounter people in the laundry room, to have to face people and see ourselves in all our complexities. But I do think, if you can’t walk away easily, it’s probably better.

EDW: We talk a lot about “entanglement” in academia. But seriously thinking about the ties that keep you in a project or place is a helpful distinction. If it’s something that you don’t have a stake in, to manufacture that stake and then gain something from it is going to feel ethically dicey.

NS: At the same time, having connections across distance and making ties outside of your own backyard is really important. I don’t know if I could do what I’m doing without trying to also have a global perspective. It wouldn’t work if everyone studied only in their own backyard! But backyards are deep and global. The lessons that I learned and the perspective that I gained from doing fieldwork in Venezuela are critical to my worldview of my own backyard. I don’t think I would understand it fully otherwise. I think we have to continue to resist the trap of studying people without studying how we are enmeshed.

EDW: Obviously, I share that view, and it’s part of why I include myself as a presence in my writing. In the social sciences, it’s still not that common, and there’s even that pushback in the humanities. But that’s a hope I have for first-person, even personal writing—not necessarily autobiographical writing.

NS: Yeah, there’s a difference between being autobiographical and being critical and reflexive about your own place and relationships. When I was in graduate school, the common diss was “Oh, that’s her second project, it’s just commuter ethnography.” Meaning: She had kids, she couldn’t go far away anymore, and so she just commutes to her field.

EDW: Wow, dismissive.

NS: I know. There’s a lot of that still. My cousin introduced me to the phrase “all research is mesearch”—have you heard that?

EDW: (Laughs.) No, but I love it already.

NS: On some level, everybody’s trying to understand themselves. It’s a way of engaging with the work you do. That doesn’t mean that’s all we’re doing.

EDW: It just feels disingenuous to me when I don’t explicitly acknowledge my presence.

NS: I’m teaching a Decolonizing Methodologies course in anthropology here at the CUNY Graduate Center. As much as anthropology is trying to move away research practices that serve only the researcher, it’s a struggle. The whole course, I was trying to get students to think—you know, you don’t have to go this way, but what if you reimagined your project to be more engaged, to be more accountable, to be creating knowledge with people about what their knowledge priorities are rather than your knowledge priorities and advancing whatever theoretical bug you’re excited about. And…I’ve faced more pushback than I expected. Part of it is not knowing any other way or not having many examples of engaged work that is also seen as theoretically engaged or sophisticated somehow. I think it’s the fear that this isn’t going to get them funding, that this isn’t going to get them a job. And it’s so real.

EDW: One of the pieces you sent me includes a bio that describes you as a “scholar-activist.”

NS: Yeah.

EDW: This is something that I think about constantly because I have an unsettled relationship to it—

NS: Because you’re a “writer-activist.” (Laughs.)

EDW: (Laughs.) It’s something I aspire to, but I was laughing because I read this Arundhati Roy essay from 2002 in which she writes “I am, apparently, a writer-activist. (Like a sofa-bed.) Why does that make me flinch?” I think, for Roy, making a distinction between the two deflates the power of writing. I don’t necessarily agree, but I see her point. I’m curious if you have any thoughts about that—and not just the label. How can scholarship further activist goals, and how might organizing influence your scholarship?

NS: It was painful for me to write that bio because I sometimes feel like an imposter. Do I really count as a “scholar-activist”? But that’s what I aspire to be, and I want to hold myself to it by publicly stating that that’s what I am so that, maybe, that’s what I can be. What’s my role in helping to organize movements? It’s what I want to do and what I hope I can do.

Being involved in different organizing projects, including the PSC (People’s Staff Congress) our faculty and staff union at CUNY, is so helpful to me to understand social theory. How we create connections, what divides us, what people are facing, what the relationship between structure and agency is, how we create a new consensus —all of those things, I can’t imagine thinking of them only in the abstract. I think scholars are insecure, often, about what our work can do for activists, but the activists are already using theory. Constantly. When I was in Venezuela, there were Grasmsci reading groups in working class neighborhoods. And in New York City, I’ve seen activist organizations do similar things. The theory is everywhere, people are tapped into it. The question for me is: how can I write in a way that’s useful because I’ve been trained in a way that is really not useful. And I’m struggling with my voice right now as I transition—I’m not writing this to get tenure or defend my ability to support myself. This can be what I want it to be, and I’m having trouble finding my voice. And I loved your book, the clarity of the voice. And I think that’s such an important thing to do. And in a different vein, Samuel Stein’s work is a good example. Activist groups in the city have looked to Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State. If it’s well-written and it’s clear, there’s no way people aren’t going to use it if it’s useful to them.

EDW: You mentioned your work in labor organizing. Do you see labor activism as directly connected to your work on climate justice? Has your work in one enriched your work in another?

NS: I think any leftist social movement organizing is a climate project, even if it’s not explicitly about “the environment.” It’s building strength and fighting for power for the collective good. I have learned so much from Carolina Bank Muñoz, Maddy Fox, Mobina Hashmi, Lawrence Johson, and other incredible union comrades at Brooklyn College. Anti-racist union organizing is part of the climate fight. There’s no way to advance a platform for climate justice if we’re not mobilizing in all these other ways.

Union organizing with students, faculty, and staff at Brooklyn College, December 2022. (PSC-CUNY)

EDW: One connection I see is in housing organizing. The goal there should be to change our utilities system in the city.

NS: The Public Power Campaign.

EDW: Exactly. We should have publicly-owned utilities, not these monopoly companies doing terrible things and shutting people out.

There are unlikely connections to climate everywhere. And I’m curious, with your students, and also maybe in your neighborhood, do you encounter any frequent misconceptions about climate or environmental justice, and if so, what are they and how do you address them?

NS: Last semester, at Brooklyn College, I taught this class called People, Nature, Culture, and it was the first time I’d taught a course on climate issues. What I found deeply upsetting was the sense, coming from the students, that there’s nothing we can do about this. I had to figure out how to step back from that without being too rosy. I tried to take that feeling in rather than just battle it with, “No, we need to fight!” I had to figure out how to teach through that and address climate anxiety.

EDW: That resonates with me. I’ve been called by my students “Well-meaning but unrealistic.” (Laughs.) Last semester, I taught Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower. It was really fun, but I—stupid me—had not anticipated that they’d feel so depressed and bereft at the end. I had to spend several class sessions emphasizing that the world is not ending. I had to backpedal. It was a good lesson for me.

NS: Yeah, Octavia Butler. I still so vividly have those scenes from Parable of the Sower in my mind, which is great, but… (Laughs.)

EDW: Yeah, my students were horrified. They were like, This isn’t a dystopian future. This is describing the present. She really had a lot of foresight in responding to what was happening in the moment. That’s a truly gifted writer.

NS: I’m a fellow at the Seminar on Globalization and Social Change at the CUNY Graduate Center, and the theme is “Climate” this year, and last week we read Max Ajl’s A People’s New Green Deal, which is, in some ways, a response to A Planet to Win, and there were parts where he’s very ungenerous, but he’s trying to make it much more focused on planetary goals rooted in the Global South, bringing together anti-imperialist movements. But he has these visions of what we could do, and I definitely want to teach that next time. It’s totally readable. But I really think it’s important to imagine other futures even though Max Ajl’s book is frustrating because it doesn’t tell you how we can get from here to there! How do we do that? (Laughs)

EDW: Besides Ajl’s book, are you reading anything right now that you’d recommend?

NS: Today, we read Mike Davis’s Victorian Holocausts— incredible.

EDW: I’ve never read it.

NS: I’m also addicted to The Dig podcast. I just take all my book recommendation cues from Dan Denvir.

EDW: It’s such a good resource.

Well, it’s such a pleasure to have this conversation with you, Naomi. Thank you!