The Craft We Didn’t Learn: Retroactive Writing Advice from the Archives

March 5, 2021

Iris Cushing, Megan Paslawski, Zohra Saed, and Kendra Sullivan

reverend angel kyodo williams, founder of Transformative Change, a center dedicated to taking care of the inner lives of leaders in social, racial, and broad-based justice movements, writes about purpose and meaning being two mutually reinforcing drivers in her life. To paraphrase, she says purpose is how one acts in and on the world(s) one inhabits in order to further progressive change; and meaning is how one understands and makes sense of those world(s). For me, poetry is the place where purpose and meaning meet.

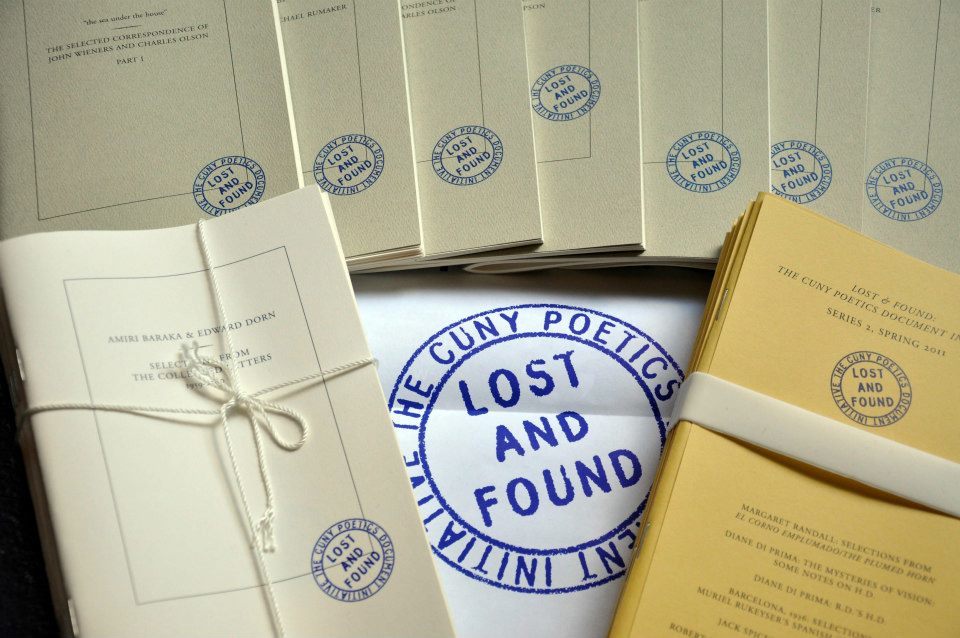

In January, Lost & Found editors Iris Cushing, Megan Paslawski, Zohra Saed and I recorded a talk for the annual Association of Writers & Writing Programs about time spent and writing practices learned in the archives of poets Diane di Prima, Mary Korte, Lucia Berlin, and Langston Hughes. We talked about the ways poetry is a bridge between the living and the dead, the individual and the collective, the work we do to stay alive and the work we do to write, and the inner and material conditions of a life organized around writing.

For di Prima, Berlin, and Hughes, work, life, and writing were all part of the stratified ground upon which meaning was made and shared with babies, friends, accomplices, colleagues, comrades, and ancestors. A strain of cultural critique and social, racial, and environmental justice ran deep in each of their diverse practices, and each entertained moral––and in the case of Hughes, mortal––risks that informed their writing.

Megan Paslawski described our panel as a conversation about instructional writing history of figures who––for reasons encompassing race, class, gender, sexuality, and the independence of their artistic visions––often worked outside the literary establishment. Together, over two one-hour talks, Iris, Megan, Zohra, and I thought about the ways in which archives have contributed to our evolving understanding and practice of the craft of writing.

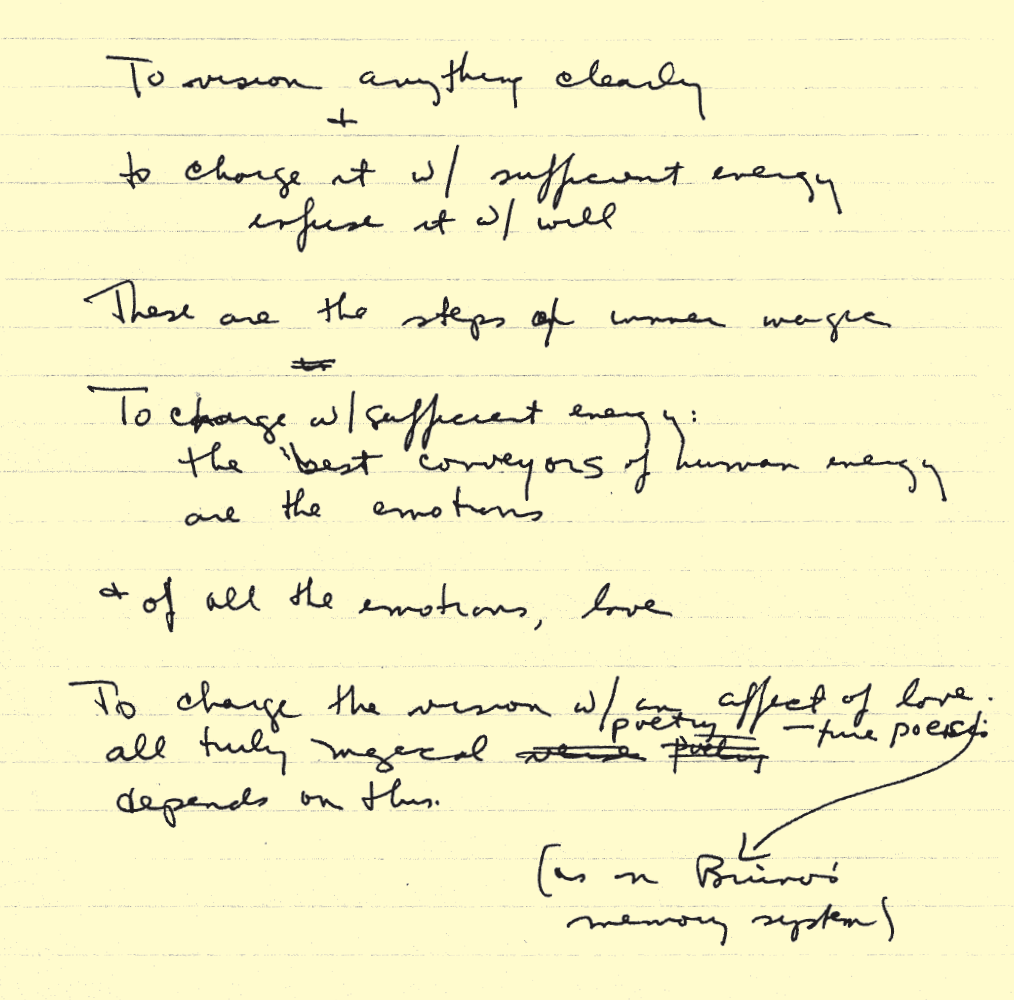

Iris Cushing began by seating Diane di Prima’s practice in direct conversation with Percy Shelley’s, who sought to ignite revolutionary change in the hearts and minds of readers. For di Prima, and for Iris after Diane’s passing, poetry is a mode of mediumship wherein direct transmission between the living and the dead is engineered through magical protocols. For me, Diane’s earthy writing binds esoteric practice to lived experience. Her poems help her readers swim into total onto-epistemological transformation while also managing a commune, opening your home to a traveler in need, or changing a diaper. Iris talked about how Diane, in life, taught her how to have a fair-minded and reciprocal working relationship with the dead and how to listen to intuition as an expert guide in poetic and scholarly pursuits.

Zohra Saed described archival research as pushing a hand through the veil of time. In the archive, at least, time is bidirectional, the past and present mutually instantiating. In addition to being rigorous, for Saed archival research is also spiritual, grounded in the study of both material and immaterial histories. Like di Prima, Saed interprets information sourced from intuition, dreams, hauntings, handwriting, and personal biography alongside the physical artifacts of Langston Hughes’ writing life. By interweaving her story with Hughes’, Saed shines a light on a conversation about history and writing that only she and Hughes could share.

Megan Paslawski who brought us all together, talked about how practically––and financially––difficult it was for Lucia Berlin to maintain her stance as an outsider, a position necessary for the maintenance of the moral and aesthetic clarity that are hallmarks of her autofiction. Berlin resisted establishment-conferred success at all opportunities, assiduously refusing entry whenever doors were opened to her. She famously worked at the intake desk of an emergency room. There, Paslawski said, she honed her craft but also her humanity, learning to value care over sentiment, trust over fear, and embraced pain as the price of being whole. It was here, I think, that she found permanent residence in the extreme “outside” at the very heart of life, where chaos and order crash into a plexiglass window, where no one belongs (for long, anyway) but almost everyone passes through en route to treatment or eternity.

–Kendra Sullivan, publisher of Lost & Found

Below are additional thoughts from our intrepid editors:

Kendra Sullivan: What would the writer(s) you edited think of this panel’s purpose? Did they understand their work as somehow marginalized and therefore in need of this kind of amplification, or could this framework be doing an epistemological disservice to our sense of their contexts?

Megan Paslawski: This is something that keeps me up at night, honestly. There’s a real burning distaste for over-academicized folderol in Lucia’s letters that occasionally comes across as frustration with “Berkeley lesbians.” I actually think she’s right about this, that there is something of the nice academic lesbian in my instinct to recuperate her work in this way. Lucia was not someone who was particularly interested in being passively recuperated or enlisted in literary scenes. That said, I think her work should be amplified and that the simplistic and simplifying logics of recognition she tried to position herself outside of should take some of the blame for how late a wider audience came to her work.

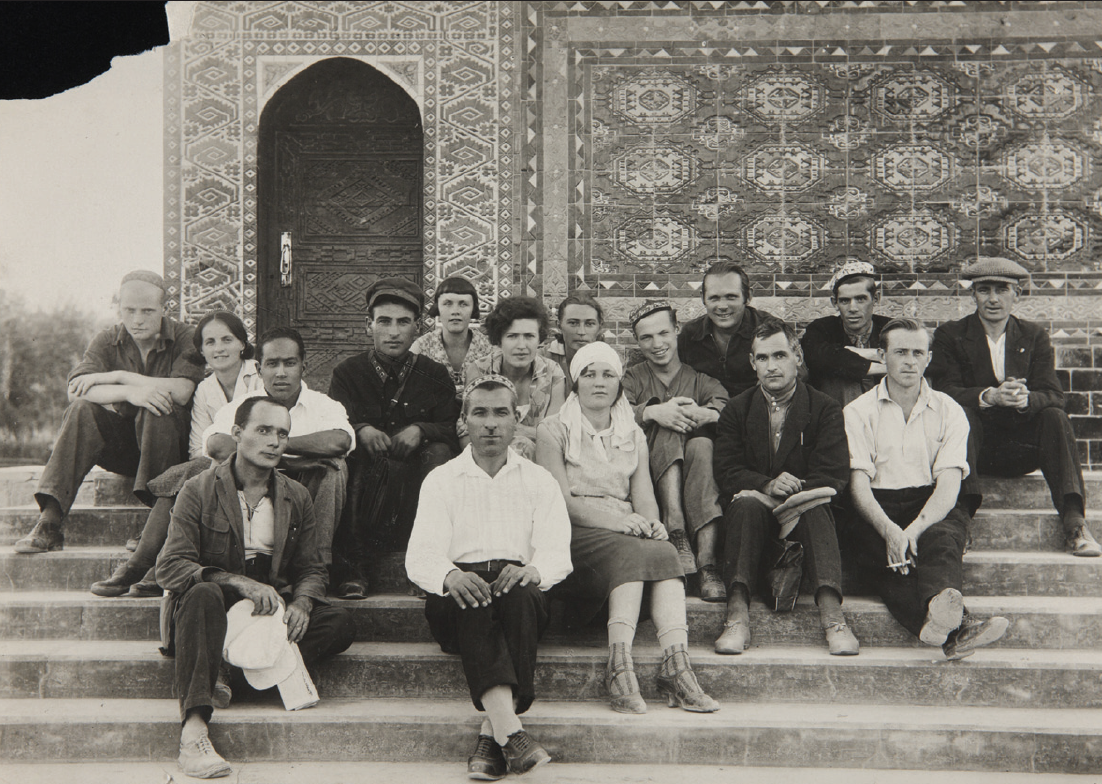

Zohra Saed: Yes, absolutely. Hughes is an African American writer and he visited the Soviet Union during the Jim Crow era. Travel and writing, meeting and connecting with the people he met in the world is the way he transcended and opposed the racism of his time. My framework for reading Hughes is to use Central Asian philosophers, such as the foundational ibn Sina (Avicenna). For me it is a continuation of Hughes’ practice of making connections and building community where he traveled in the world.

KS: While working on your chapbooks, did you come across other writers in your authors’ circle whose aesthetic vision or historical positioning became clearer as you learned of this friendship?

MP:My co-editor Claudia Moreno Parsons and I have talked a lot about how Ed Dorn was in some ways an unlikely mentor for the kind of writing that Lucia was doing, but in terms of aesthetic vision they shared a mutual hatred for hypocrisy and cant. We’ve also been drawn to the ways that Jennifer Dorn showed herself to be such a committed editor and friend. Claudia knows far more about the Dorns than I do, so for me it was the first time I really encountered Jennie in her own right.

ZS: Yes, Hughes kept a time capsule of work given to him by many Central Asian poets. Some were killed during the Stalin purges, others during World War II. Some survived and became the founding literary voices of Soviet Central Asian literature. He translated the work of Ghafur Ghulam into English. He attempted to translate some of the Turkmen poets he met, like Shali Kekilov. Even if it took three languages to translate the poems, Uzbek to Russian to French to English, he made it work.

KS: We’ve talked about the craft work of individual writers published by Lost & Found, but does the press as a whole have a vision of good writing that guides its publication decisions, either consciously or visible retroactively?

Iris Cushing: If I were to characterize the vision of Lost & Found as a whole, I would say that it’s a vision that finds the origins of what we might think of as “good writing,” and reveals the relationship between those origins and the writing itself. Here’s a metaphor that comes to mind: I have a friend who is an organic farmer, who told me once that the farmer’s job isn’t to “grow” the plants. It’s the earth that grows the plants, and it’s the farmer’s job to facilitate that growth with the lightest touch possible––to create actions that allow a transformation to happen, but then get out of the way. I think that metaphor applies to the way L&F editors work with the texts we’re editing. We find something extraordinary, something that’s been overlooked, something that illuminates a whole network of ideas. And we handle it carefully, to present it to the world exactly as it is, in all its beauty, so that it can do its own work.

ZS: When I started writing about the material in Hughes’ papers, I had been translating so much from Uzbek and Turkmen that I couldn’t see straight in English. I know it took an incredible Lost & Found community of editors to get me back to writing. This really means that everyone listened to me talk it through and then I was able to write it out afterwards. I found an incredible family of editors and scholars in Lost & Found. I know that what kept me going in research and in writing was Ammiel’s constant suggestion, “Follow the person.” And the more I followed Hughes’ notes and his photos, the more the story unraveled for me. I appreciated the allowance of creativity in our own voice while we wrote about these incredible poets.

KS: Are there differences in how you’d approach an author as a “retroactive writing instructor” when considering their work posthumously as opposed to writers who are still living but not perhaps not pedagogically active or broadly promoting their expertise?

IC: I feel like I can answer this because I worked firsthand with di Prima for years while she was alive, and am still learning from her now that she’s gone. It was a really incredible experience reading di Prima’s work, and gradually wrapping my mind around the breadth of her research and intellectual innovation, and then meeting with her and talking about the work she’d done. I learned early on that it was better not to ask questions–––rather, our conversations flowed freely when we started off talking about “ordinary” stuff (the news, our families, the weather) and then gradually shifted into discussing writing practices, literary histories, research, ways to meld scholarship and creative liberation. Stories and insights would emerge from our conversations that ended up being SO essential to me, but I never would have even known what questions to ask to arrive at those moments. When di Prima passed away in the fall of last year, I found myself carrying this spirit of “disinterested inquiry”––that is, a willingness to discover, but without the presence of a fixed “interest”––to my reading of her writings, both published and unpublished. Luckily, there’s so much of di Prima’s work that it really is possible to wander in a large territory of ideas and find new things all the time. Right now I’m looking at her unpublished memoir of the years after she left New York, starting in 1965. It’s called Grail is a Green Stone. Of course, not having di Prima here to talk with is definitely hard, for all kinds of reasons. Sometimes I’ll be reading through some notes or a draft of something and find a note to myself, “ask Diane about this,” and feel gutted that this is no longer possible.

ZS: For me, the communication with Hughes was all through spiritual acts of visiting regularly where Hughes’ ashes are interred, right under the medallion in the foyer of The Schomburg. When stuck or lost in the search to patch together the connections he had made with Central Asian writers and artists, I would also sit at the steps of his brownstone, before it became a cultural center. These were very effective for me. I wanted to be at peace knowing that I pieced together his notebooks and his photos with great respect.

KS: For those of you who have published L&F chapbooks on two or more writers, did these writers more or less share a vision of good writing or were their approaches to craft wildly different? What do you as a reader and a writer take away from comparing their artistic practices?

MP: I see some connections between Michael Rumaker and Lucia’s approaches to realism that we might attribute to Black Mountain College or at least BMC by proxy. I think they were both very attuned to the interiority of lonely people, although in the 70s and after you start to see how gay liberation had inspired Mike to find the idea of community intensely pleasurable, whereas Lucia’s narrators are often at their funniest and most insightful when pressed into undesired connections with others. Thinking about this now I keep picturing them as people writing at different edges of the same big loose literary scene, and in that respect I think their work has much to say to each other. In fact, I want to expand that metaphor outwards to encompass every Lost & Found writer!

KS: Has editing this work contributed to your own creative practice? Tell us what you’re working on!

MP: I initially didn’t think so, but I recently finished writing a short story that I think owes something to Lucia’s attitude towards working. In her stories, work often seems inherently absurd even as it mercilessly consumes your life. Or, perhaps I read Lucia that way because I feel some of that myself. Anyway, the story features a character who’s a reluctant employee at a wizard cosplay bar.

ZS: The Hughes archives were incredibly neat and organized. Hughes kept his notes, he stapled notes on with summaries on journals. He kept every shred of writing and doodles. I started incorporating more doodling into my note keeping, and it has been helpful and therapeutic. I don’t think I can replicate anything Hughes has done in his lifetime. But like Hughes, I also translate poetry as a way to create a sense of community. For me translation is also creative. I see the way Hughes translated Uzbek poems, and he caught the music of the words and the rhythm better than other poets who have translated from the Uzbek. So I would say, I’ve become a better listener to the music of poems when translating.