Vanessa S. Troiano, a Ph.D. candidate in Art History at the CUNY Graduate Center, reflects upon working with American artist Susan Weil to document her nearly 40-year practice of synthesizing art and poetry into daily poemumbles. Supported by an archival grant from Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative, Troiano’s research forms part of her dissertation, “Susan Weil: Artistic Trailblazer,” the first scholarly monograph to survey Weil’s career.

American painter/poet Susan Weil (b. 1930) began her life-long visual and linguistic approach to artmaking in the late 1940s as a student at Black Mountain College, where she came of age among a generation of postwar artists reviving avant-garde techniques. By 1984, Weil refined her experiments with image and word combinations into a daily poemumble, a self-coined portmanteau of poem and mumble describing her unique synthesis of fine art and poetry. At 92, Weil continues to make poemumbles, which today number over 12,000. With the support of an archival grant from Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative, I was able to explore her mostly unpublished body of work for my doctoral research at the CUNY Graduate Center. Weil’s contributions to art and poetry remain largely unknown, which my dissertation seeks to rectify as the first scholarly monograph to survey Weil’s career.

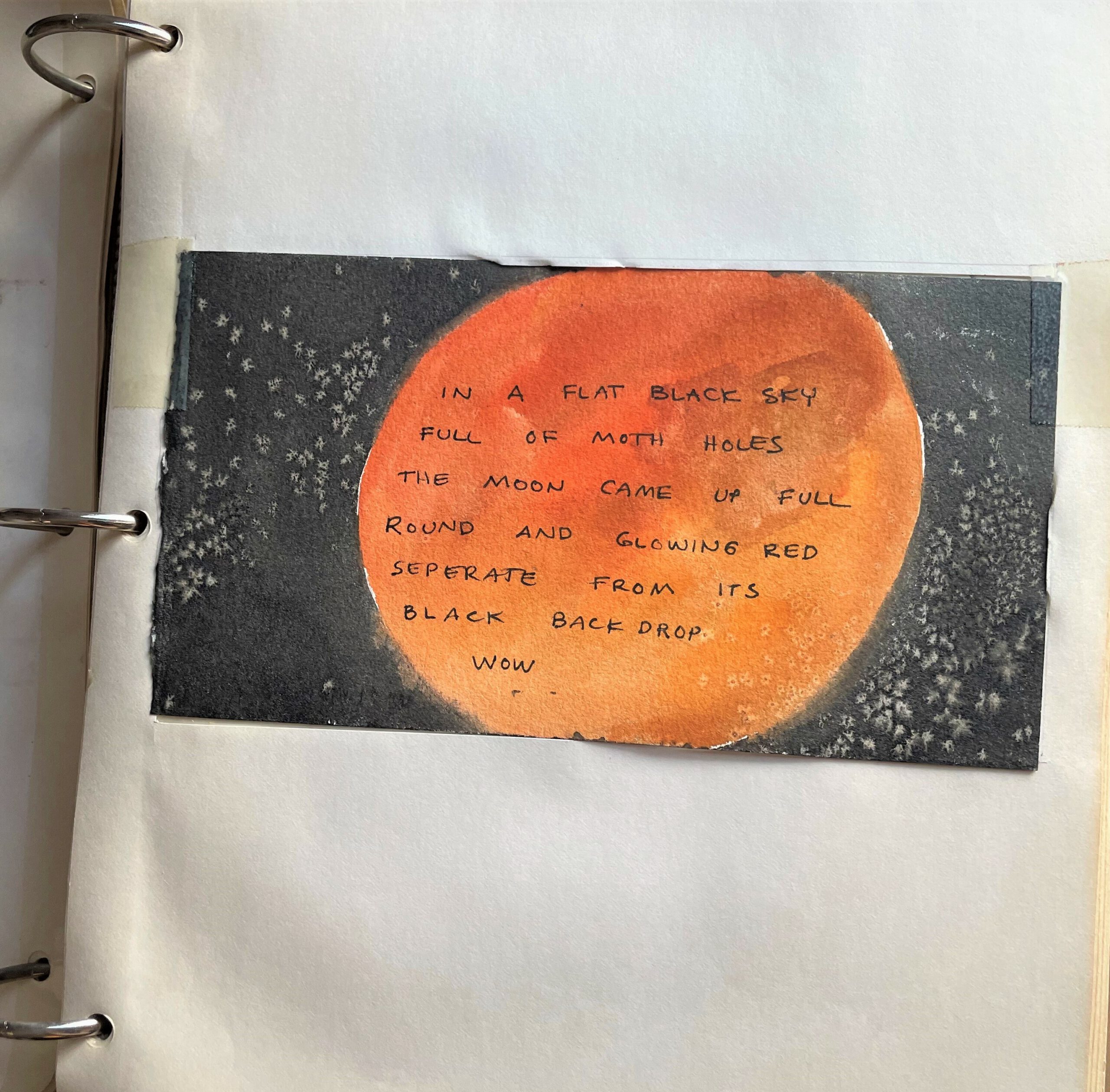

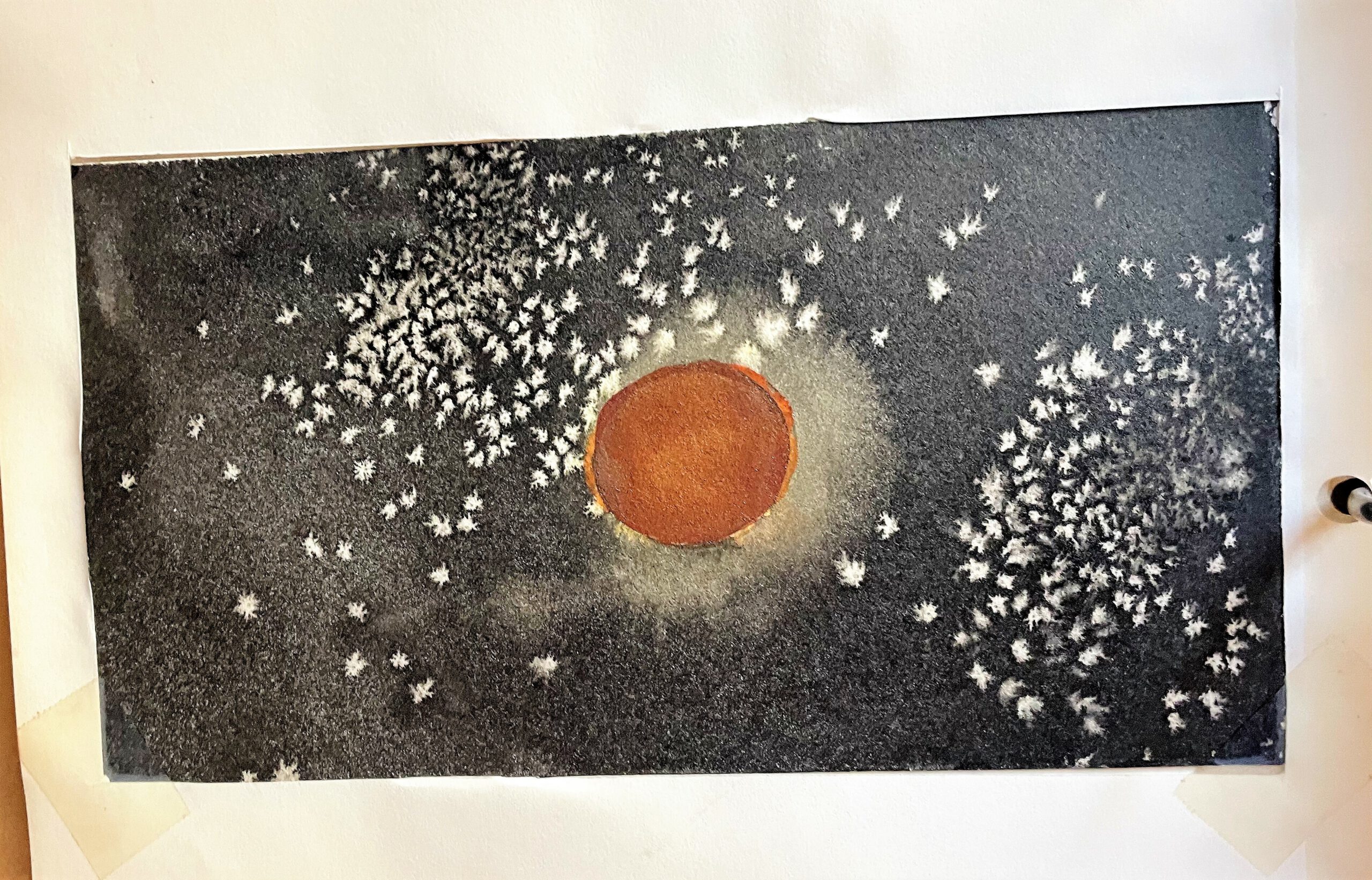

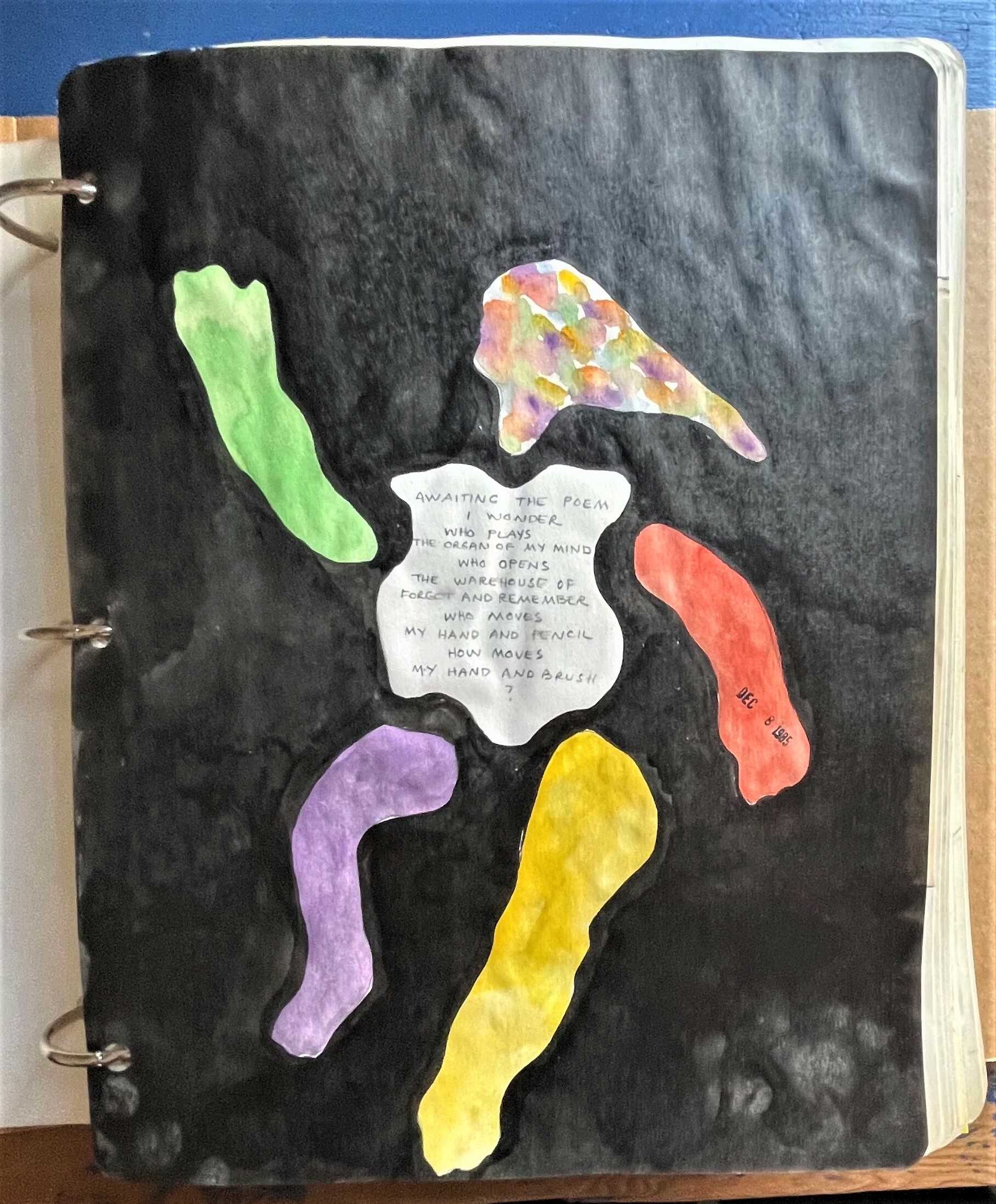

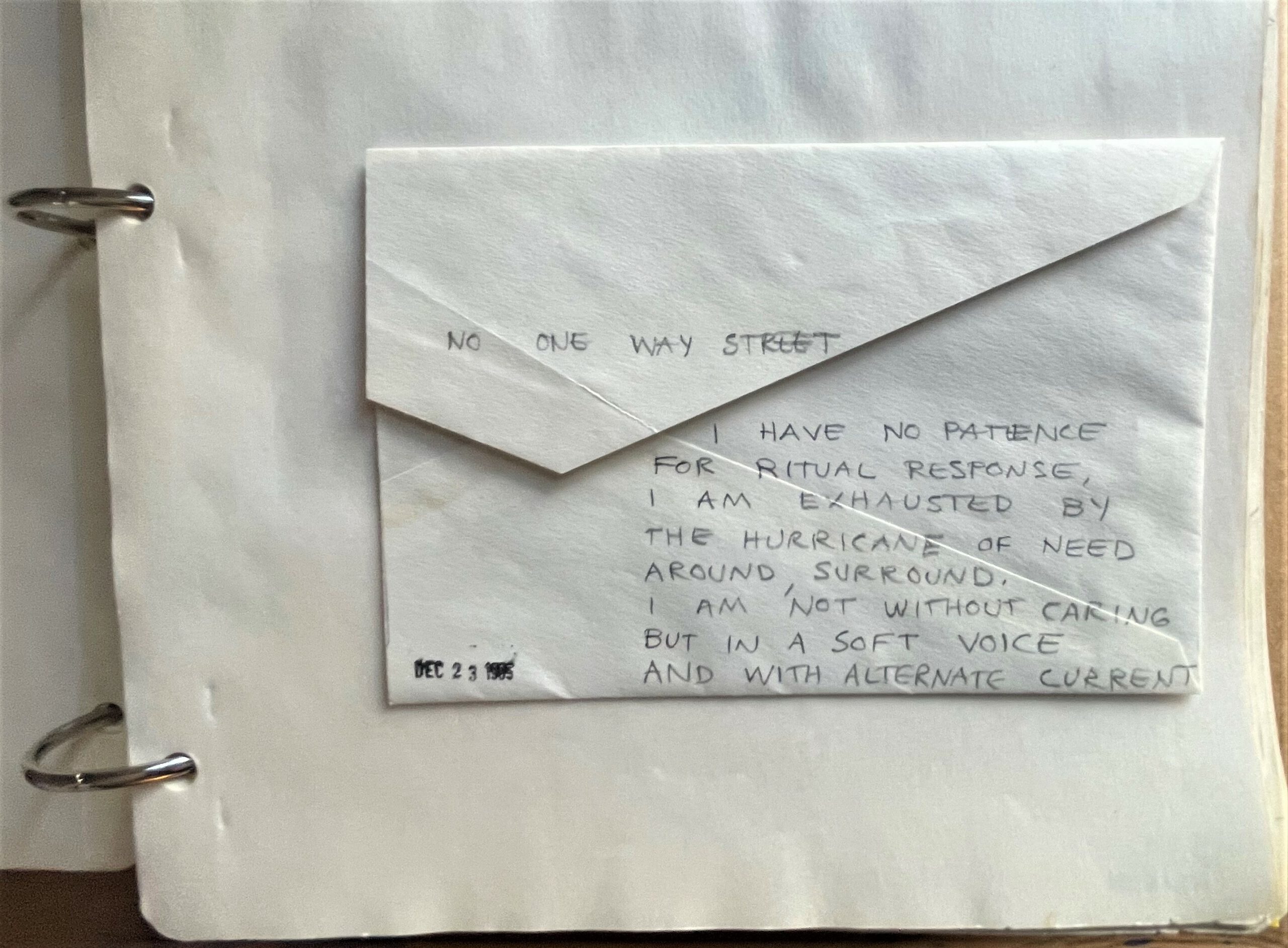

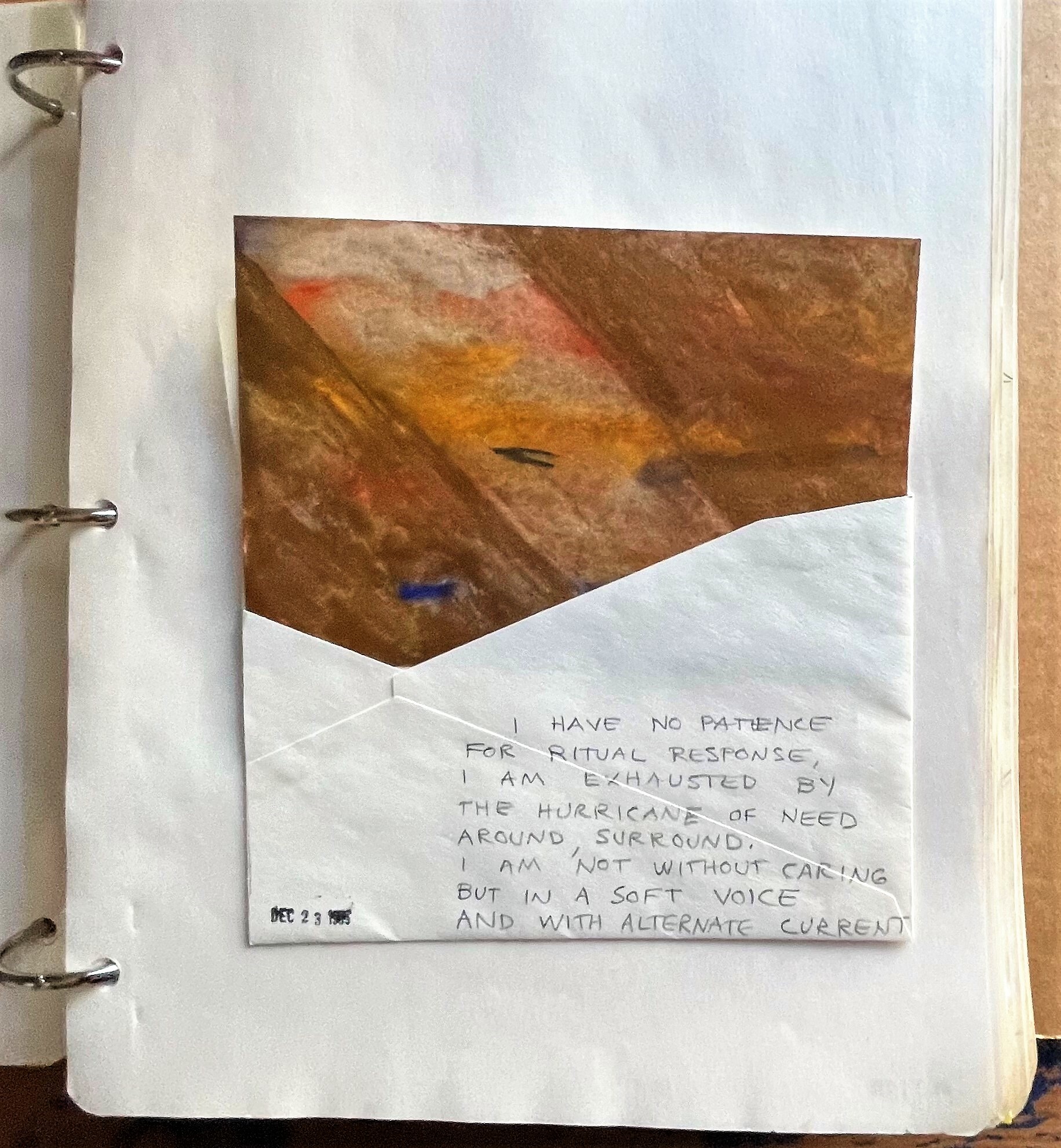

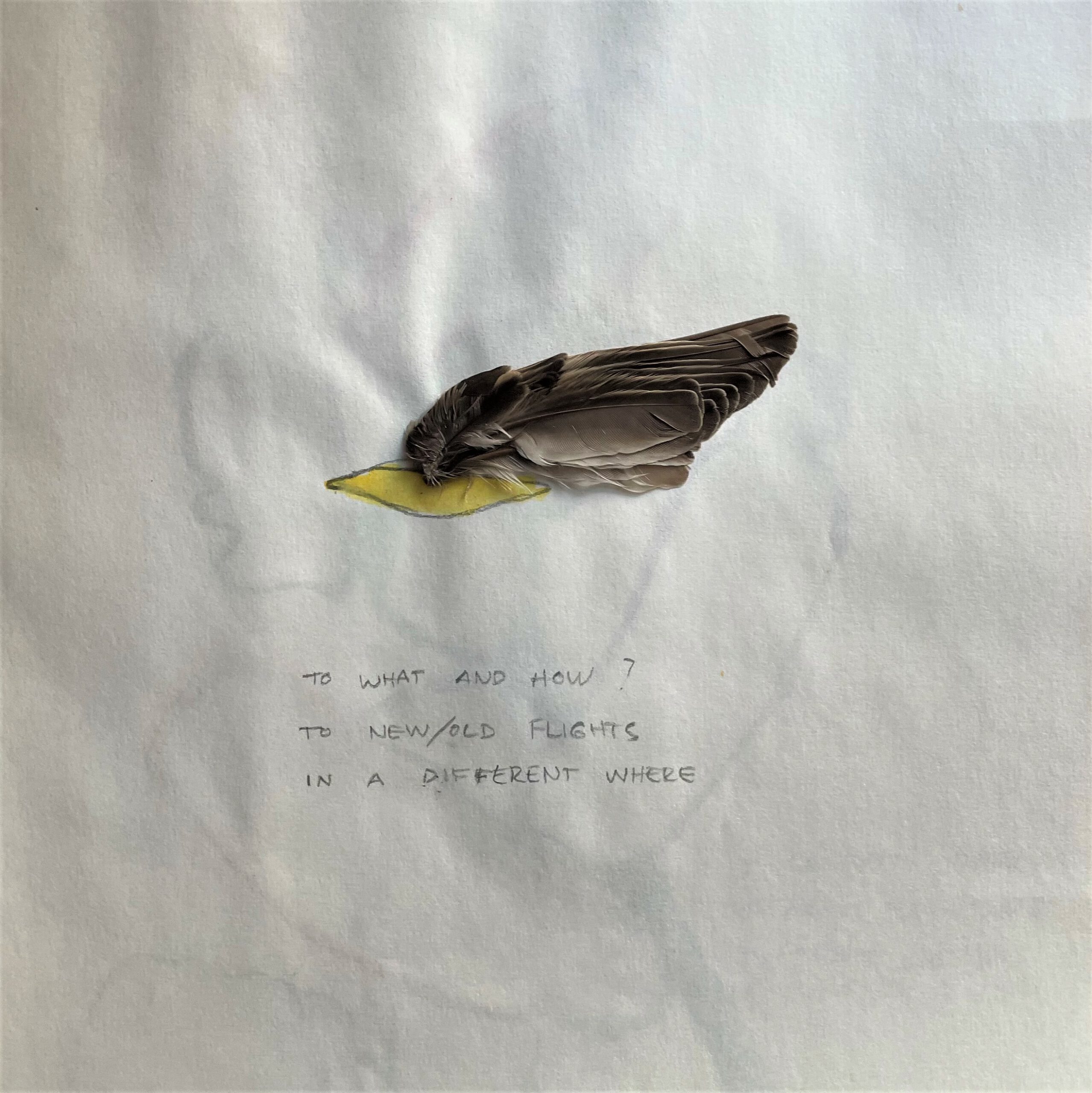

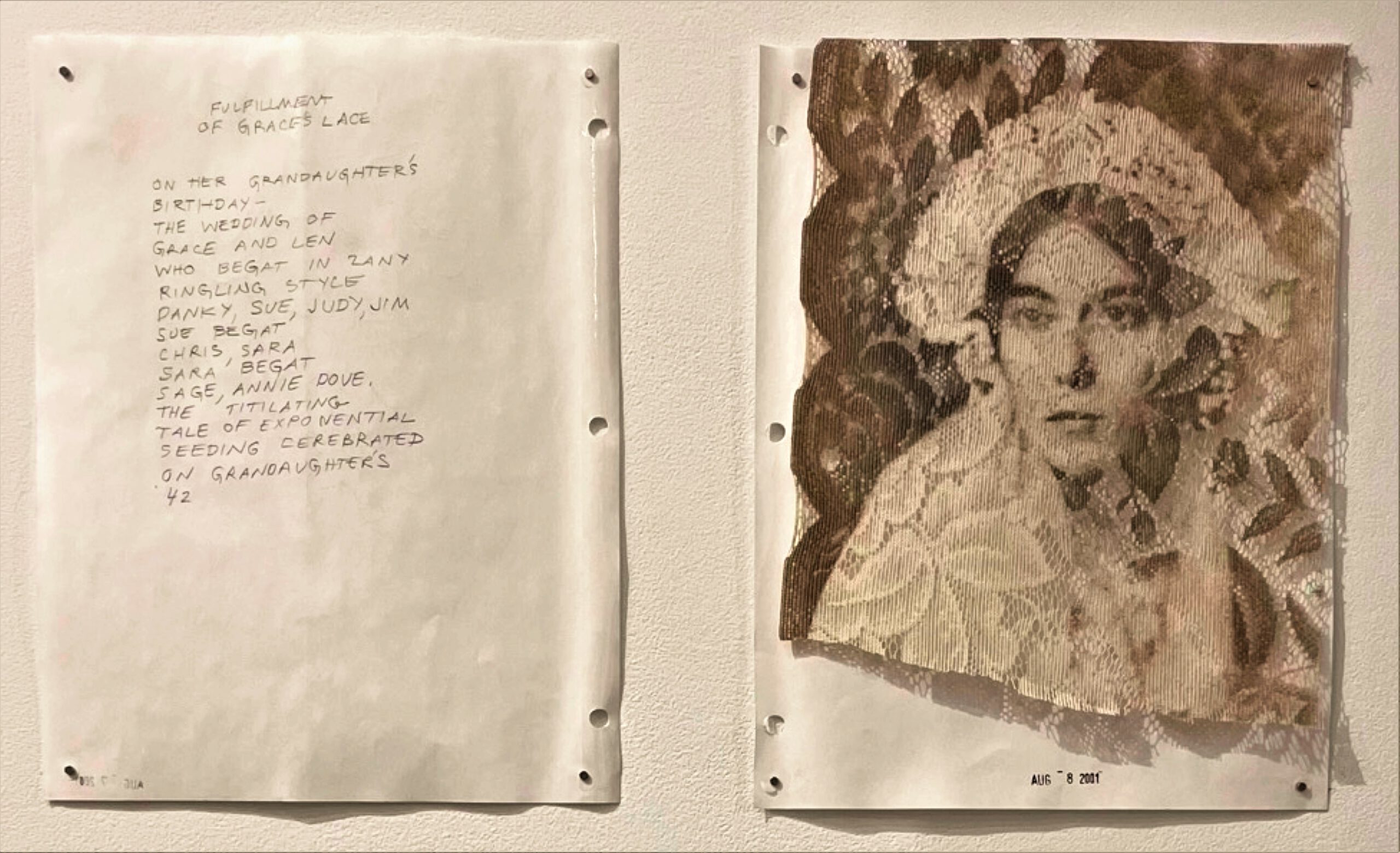

Weil’s poemumbles have a boundless subject range realized through juxtapositions and collages of handwritten and typed poetry with original and appropriated images. Catalyzed by either a word or image, Weil challenges herself to create “a visual equivalent for a word experience” or “a word equivalent for a visual image.”[1]

Neither the image nor the poem is intended to illustrate or explain the other. Rather, they exist together, unified in a creative expression that transcends the boundaries of their distinct forms. For Weil, poetry is about “making words in relation to an image or making words around a thought or experience. It can be long, it can be short, it can be any which way.”[2] Weil has refused to acquiesce to conventional expectations, especially for women of her era, and her uninhibited creativity continues to expand definitions of art.

Weil remains dedicated to creating poemumbles, even while traveling, and shares copies with select friends and family. Her only extended pause occurred during the illness and bereavement of her late husband, Bernard Kirschenbaum (1924-2016), who was also a multi-talented artist. Weil resumed her daily practice in March 2020 at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown in New York City. Since then, instead of making poemumbles by hand, she digitally assembles images and words so that she can more easily share them with family and friends. Weil had already come to embrace computer and internet technologies in her painterly practice in recent decades. Her present-day poemumble adaptation is a testament to her enduring artistic engagement with the contemporary world.

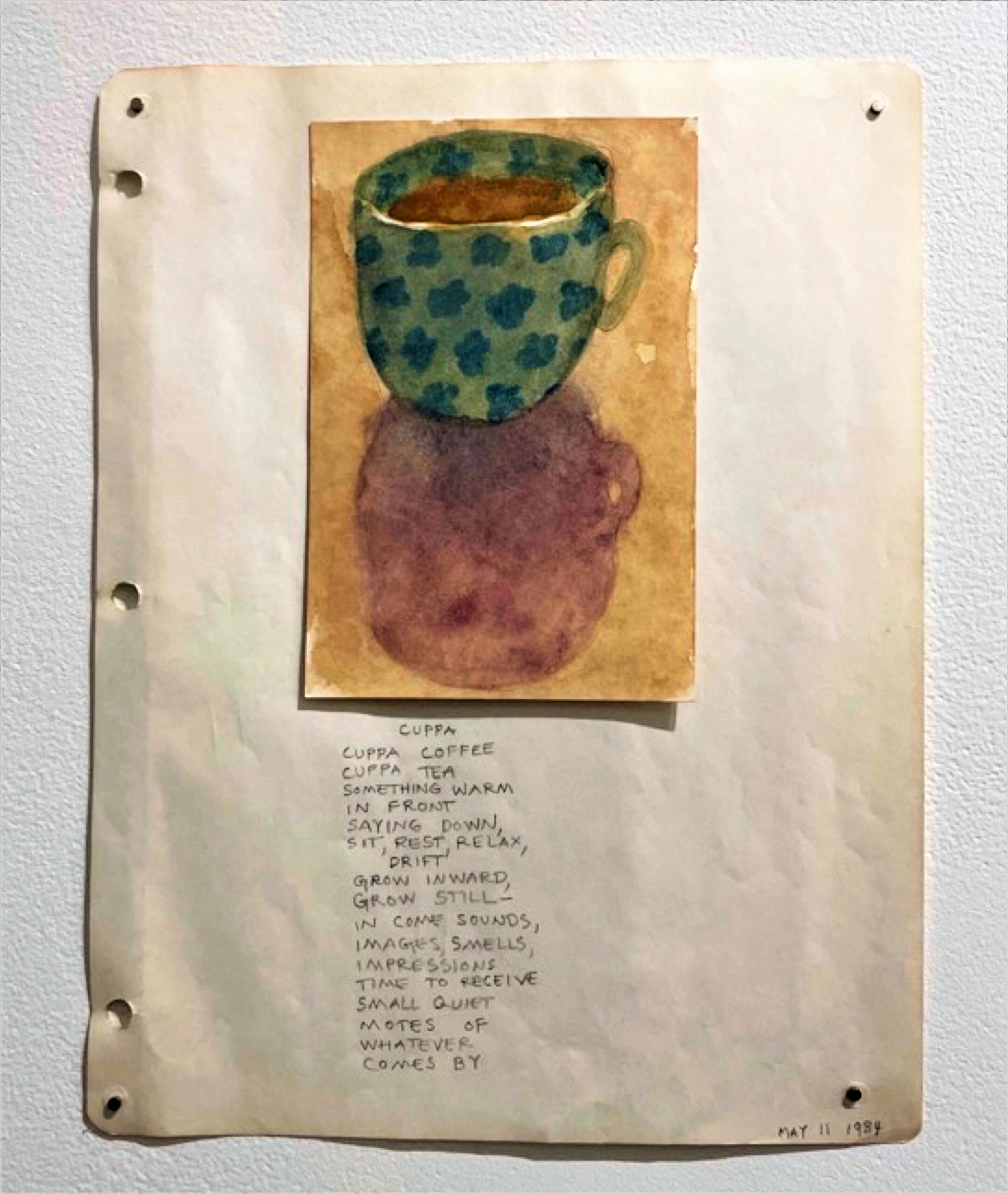

Weil stores her poemumbles in approximately 80 binders at her home, where she welcomed me to enjoy a cup of coffee with her before beginning my research. The simple pleasure of drinking a cup of coffee inspired Weil’s first poemumble in 1984 and it has been part of her daily practice ever since. Entitled Cuppa, her first poemumble consists of a painted cup of coffee in colorful green and blue watercolors alongside an original handwritten poem:

Cuppa coffee

Cuppa tea

Something warm

In front

Saying down,

Sit, rest, relax,

Drift

Grow inward,

Grow still—

In come sounds,

Images, smells,

Impressions

Time to receive

Small quiet

Motes of

Whatever

Comes by

These words exemplify the quiet observation and personal reflection of Weil’s poemumble practice, which she begins every morning shortly after waking—a time she finds particularly generative. She explains, “When you’re coming out of a sleep state in an interior mood, it’s easier to find your own thoughts. It’s when I think through new ideas or imagine what I’m going to do in the studio.”[3] Intimate and witty, Weil’s poemumbles offer diaristic insight into the creative thought and context of her artworks.

As I looked through the binders, I was overwhelmed by the seemingly endless variety of poemumbles. For some of them, Weil arranged the image and poem side-by-side; for others, she combined text and imagery together in one composition. Many poemumbles also take the form of concrete poetry such that the arrangement of the poem’s words creates the image. Several solicit tactile viewer-reader interactions to open folds that reveal surprises. As with most of Weil’s art, photographic reproductions of her handmade poemumbles are poor substitutes for their vivid, in-person experience. Her poemumbles are often multidimensional, vibrantly colored, and textured with multimedia, including lace, feathers, and strings. Yet, they are still compact enough to be filed as folios in a binder. I was also impressed by how cleverly Weil preserved double-sided poemumbles, affixing them to cut-outs on binder paper to display both sides.

Writing an art historical dissertation about Susan Weil is an exciting challenge: the discipline tends to categorize art by styles and periods, but Weil’s work defies categorization. As suggested by Ammiel Alcalay, an editor of Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative, I strive to “follow the person” in my research. Alcalay encourages us to, “Forget about schools and categories but delve into a person’s journals or correspondence or lectures and see whom they pay attention to, whom they refer to, whom they ignore, what they’re reading, what they’re not reading, and so on. This immediately provides a different history than the ones we’re used to getting: all of a sudden you realize how closely connected as many of these writers who have been divided up into schools like different kinds of fish actually are.”[4]

Any attempt to box Weil into one movement or style diminishes the brilliance of her multifaceted oeuvre. CUNY’s archival research grant has assisted my efforts to trace Weil’s interconnected artistic and poetic relations and, as a result, strengthened my understanding of the intricate networks involved in modern and contemporary creative practices. I am most grateful to Susan Weil, her family, and her studio for giving me such privileged access to her art and life and supporting my dissertation’s work to inscribe her achievements into the history of art.

NOTES:

[1] Susan Weil, quoted in Donna Stein, Susan Weil: Full Circle (Asheville, N.C.: Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center, 1998), p. 3.

[2] Susan Weil in conversation with Vanessa S. Troiano, July 14, 2022.

[3] Weil, quoted in Stein, ibid.

[4] Ammiel Alcalay in conversation with Harriet Staff, “Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative.” Originally published June 20, 2011. Available at https://www.poetryfoundation.o…. Last accessed September 15, 2022.