On The Letters of Rosemary and Bernadette Mayer, 1976–1980: An Interview with Gillian Sneed and Marie Warsh

May 24, 2023

It’s astonishing to me that there is so much in Memory, yet so much is left out: emotions, thoughts, sex, the relationship between poetry and light, storytelling, walking, and voyaging to name a few. I thought by using both sound and image, I could include everything, but so far, that is not so.

—Bernadette Mayer, November 2019

In the above quote, Bernadette’s thoughts on her seminal Memory (1972) elucidate what for me is a central question to both her work and Rosemary’s: how can the ephemerality of experience exist in the age of mechanical reproduction? How can art not simply represent life within the confines of scientific progress, but present it in a way that formidably contends with the totalizing forces of the modern world?

In perhaps her most significant work, Midwinter Day (1982), Bernadette produced an epic document of the course of a single day, anchored in the details of her domestic life, but given also to dream, fantasy, aspiration, philosophy, and abstraction. As much as it feels like a dense, frame-by-frame record of passing time, each page is also pressurized by an incalculable vitality. Rather than failing to “include everything,” Bernadette’s work is, for me, a celebratory demonstration of how the ambition to grasp it all that defines our Capitalist era can never actually achieve its aim. No matter how hard-working or inventive you can be—and Bernadette was among our most dedicated and ingenious—it is a beautiful fate that life itself extends beyond the bounds of our calculations and capacities. The voyage cannot be bottled and sold, it must be undertaken if you wish to live it.

Where Bernadette’s writing was at times grounded in the development of maximalist forms, Rosemary’s art utilized the ephemeral, but in distinctly subversive contexts: sculptures of draped fabric, town histories carved in snow. A poignant example is “Some Days in April,” a memorial to friend Ree Morton and to her parents. One of her “temporary monuments,” “Some Days in April” consisted of high-flying weather balloons staked to a field in upstate New York, each balloon painted with the names of stars, flowers, historical figures, and mythological characters that were resonant with the month of April, the month in which her parents had been born and Morton had died. In the photos documenting the piece, the bright balloons against the sky are undeniable candy, but her drawings of the ends of the heavy ropes that hold the balloons, knotted expertly around the stakes, are for me particularly moving. In the “life drawings” of these knots, there is a resonant tautness to Rosemary’s attention, and the suggestion that it is not the proposed permanence of the monument that carries memories forward, but instead the degree of ceremony with which we devote ourselves to time, place, and our connections to each other.

The Letters of Rosemary and Bernadette Mayer, 1976–1980(Lenbachhaus/Ludwig Forum/Spike Island/Swiss Institute, 2022) documents a connection between sisters. But further, it documents a period of unrivaled intellectual exchange between them, where physical distance from one another and major periods of personal artistic development conspired to produce letters that were vulnerable, adventurous, and inspired. Editors Gillian Sneed and Marie Warshspoke with me about how the project developed, how the letters served the Mayers as a means of both communication and creative practice, and how they serve readers as documents of pivotal moments for late 70s art and literary history.

— Morgan Võ

Following the interview, we include THE VANITY OF MOUNT HUNGER, a letter-poem from Bernadette to Rosemary, which first appeared in Bernadette’s The Desires of Mothers to Please Others in Letters, 1994.

*Editor’s note: Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative is proud to have supported the early archival research for this project and eventual book by its co-editor and CUNY Graduate Center alum Gillian Sneed through a 2018 L&F archival research grant, and continued our support by partnering with the book’s publishers as part of the Lost & Found Elsewhere series.

___

MORGAN VÕ: Where did this project begin? How did you come together around these letters, and what were the directions that you initially wanted to take?

GILLIAN SNEED: I would say the project actually began before the idea for The Letters. I knew Marie, just through personal connections, and around 2012 we began talking about her aunt, Rosemary Mayer, who I was really interested to learn more about, as an art historian—I was in grad school, at the CUNY Graduate Center. And so Marie and her brother Max [Warsh] facilitated the opportunity for me to meet Rosemary and conduct an interview, which was super exciting. Soon after, Marie and I began to work together to find ways to write about Rosemary’s work. Around this time Max was showing her work in exhibitions at Regina Rex, the cooperative gallery that he was involved in at the time. But it seemed like there wasn’t much interest. I pitched ideas to different journals and magazines, and no one wanted to do anything.

As with many women artists, unfortunately, it was only after she died that there was more interest, and then we began doing some collaborative writing projects. We wrote about her work and her writing for The Brooklyn Rail, and then Marie and Max later organized the volume Temporary Monuments: Work by Rosemary Mayer, 1977-1982, for which I wrote an essay.

MARIE WARSH: While she was still alive, we were also trying to share her work. In addition to trying to publish something, Gillian and her husband, artist Ricardo Valentim, were also trying to help us share the work with galleries to see if we could get a show going. But there really wasn’t that much interest, so we got a little more organized and after she died, we ended up presenting her work in Max’s studio, and set up a series of studio visits. We invited gallery people, other artists. Gillian and Ricardo helped us do that as well, and made suggestions of people to invite. From there we did get a show at Southfirst Gallery in Brooklyn. And from that show the interest started to accelerate.

What’s been really nice about this letters project is, as Gillian said last night [at the launch for The Letters, Swiss Institute, NYC, October 27th, 2022], it does feel like the culmination of this process of working together over the course of many, many years to share Rosemary’s work. What I do think has been very successful has been the writing that Gillian has helped with, as well as Rosemary’s own writing. The first time we collaborated was on an essay for The Brooklyn Rail: Anne Waldman was asked to curate a whole section of The Brooklyn Rail, and was invited to do whatever she wanted, and she asked me if there was something about Rosemary that she could include, so we wrote an essay about the importance of journals and writing in Rosemary’s practice.

Then, as part of the exhibition at Southfirst Gallery, we published the first edition of Excerpts from the 1971 Journal of Rosemary Mayer—that was also helpful, I think, in presenting Rosemary to the world. A lot of people saw this book and became very entranced with Rosemary, and her story as an artist—particularly as a young artist in 1971.

The diary publication caught the attention of Julia Klein of Soberscove Press, a publisher in Chicago, who’s very interested in artists’ writing. She approached us to see if there was any other work by Rosemary that she could possibly publish, and then we started thinking about this body of work of Rosemary’s called “Temporary Monuments” that had never been presented in a comprehensive way. It’s a series of installations made of balloons, and snow, and other fugitive materials. The works themselves are documented in photographs and drawings, but there was all this writing about them as well. So we put all this documentation together and Gillian contributed an art historical essay. In addition to explaining what the work was, that essay was important as a way to contextualize Rosemary’s work, especially with regards to monuments and monumental sculpture, and also to women working with these ideas.

SNEED: Work on The Letters started in 2018. I had been digging around in the Rosemary Mayer archives for the various research that I’d been doing. I saw some letters in there, and it occurred to me: “Where are the response letters?” Sometimes there was a letter from Bernadette, and sometimes there would be copies—Rosemary carbon-copied a lot of her letters—and I knew this was indicating that there was probably a wealth of correspondence somewhere, but it wasn’t all in the Rosemary Mayer archives. I was at the CUNY Graduate Center, and I was aware of the Lost & Found project. Marie had told me that the papers of Bernadette Mayer were at the UCSD Special Collections, so I got a Lost & Found Archival Research grant and I went to UCSD. I didn’t know what I was going to find when I arrived, and when I got there, there was an absolute treasure trove of correspondence. It was amazing. From the 60s all the way through to the 90s, when Bernadette sold her archives. Rosemary had also sold her letters from Bernadette to the archive, so the archive had both sides of their correspondence.

And so then I went through all these letters and other materials. It’s a very rich archive. I took a lot of photos, I transcribed stuff. Then I came back to Marie, and I was like, “Look—there’s some amazing stuff here, we should try to do a publication.”

We started thinking about which time period to focus on, because there are letters from all over. We homed in on 1975-1980 because the correspondence was particularly rich in this time. They were living in different places: Bernadette was living in New England, and Rosemary was living in New York. They weren’t in the same city and they couldn’t really afford to call each other on the phone, so the main way they were communicating was back and forth in letters. And ’75-’80 also happened to correspond with crucial moments in their careers. So, the letters included really good stuff about them thinking about art and poetry, the art world and the poetry world.

We started to organize the manuscript, we transcribed everything, and we started to research some things, we footnoted some things, we put things in order—some of the archive’s dating was wrong for the letters. So, together, we organized it and lightly edited it. Then we took it to Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative and brought it to Ammiel Alcalay, and he was like, “It’s probably too big for one of these chapbooks.” Because the Lost & Found publications are relatively brief. So then, we were like, “Well, we have this manuscript. Let’s try to shop it around for publishers.” And we did.

WARSH: It seemed like people were interested, but no one seemed to want to commit to it. So, it was sitting on the back-burner. Then, in 2019, Max and I started working with Swiss Institute to plan this survey of Rosemary’s work there, which was the first comprehensive survey of her work ever, really—even in her lifetime. They were looking into different places in Europe for this survey show to travel to. It became this four-stop tour—the Swiss Institute, then two museums in Germany, and one in England—and they were planning to do a catalog, but that was going to take a really long time, so they approached us about doing another publication in addition to a catalog, to exist during the course of the survey show. They asked us if there was any writing of Rosemary’s or other material for a book that would be relatively easy to put together in a short timeframe. I immediately thought of the letters as a possibility, but I wasn’t totally sure it would be the kind of thing that these art institutions would be interested in, because it really was archival material, perhaps not something that was traditionally published as part of an exhibition.

But all the curators involved in the survey tour were really struck by the letters, and how they tell the story of the time in which Bernadette and Rosemary were living and existing and working. And I think they also appreciated how the letters related to Rosemary’s ways of thinking and working, integrating personal biography and history. They captured a lot of her interests, and the things she was thinking about and reading, in ways that complimented the survey exhibitions.

VÕ: I’ve also read Excerpts from the 1971 Journal. It’s an amazing resource, to be getting such a frank record from somebody who was living as an artist from an early age, though not immediately as a breakout artist star, and so Excerpts is detailing what an artist’s life entails in a way that few records do.

SNEED: I think in the letters, too, some of those struggles come out. People really identify with the real struggles that Rosemary and Bernadette talk about so frankly. Struggling to pay rent! The heat getting cut off by your horrible landlord in the middle of winter. Having to do gigs to support your art career, and balancing all that. It’s just so relatable, and it’s so nice to hear people talking about! [laughs] Especially women artists who are trying to make it. I think there’s such a connection there for people today, when they read these letters and hear them talking about these issues.

VÕ: In terms of the epistolary form, I was wondering—in some ways, it’s very obvious for people who know both of these artists’ work—but could you talk about how letter writing as a form coincided with, or departed from, the work that they did as artists and writers?

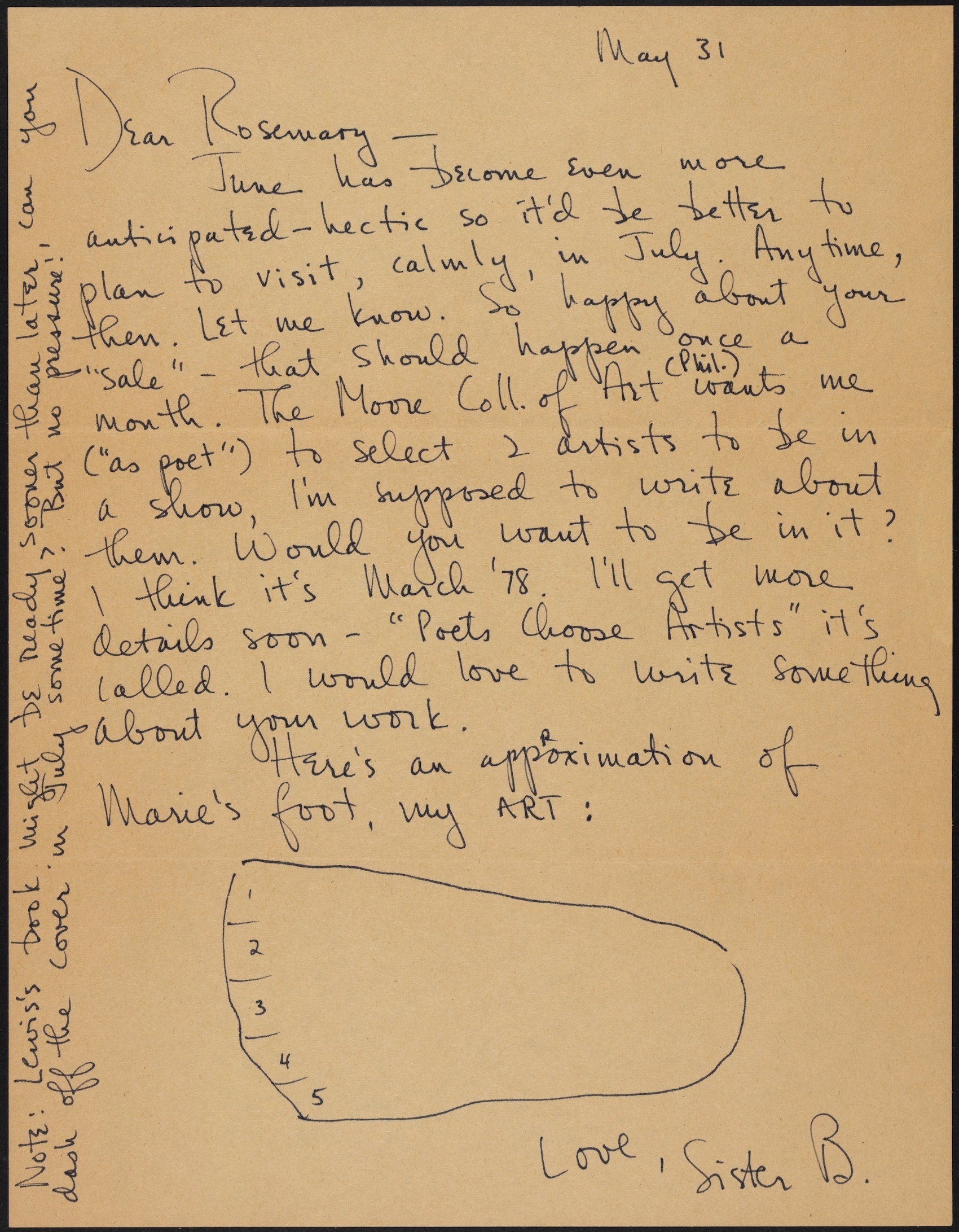

WARSH: Well, as is clear from Bernadette’s archive, she’s really a prolific letter writer, and was writing letters to so many different people all the time. It’s definitely a part of her writing world, writing these letters. I think what’s interesting—especially at the event last night, during which we read a lot of the letters aloud—in this book you really start to see the relationship between these letters and some of her poetry. In 1979, she started working on her book The Desires of Mothers to Please Others in Letters, a book in which she is making the letter writing form into poetry. Actually, one of the last letters in The Letters was found in Rosemary’s archive, but had also been published in The Desires of Mothers, and it’s very clear just in the language how it’s becoming less of a personal letter to Rosemary and more of this poetic form. She even titles the letter, and explains why she titles the letter. So, I think for Bernadette, it was really one of her forms of writing as a writer, not only as a correspondent or someone who was just trying to keep in touch with friends.

For Rosemary, I think writing letters is an extension of her journaling practice, and also her writing practice as well. Something that comes across throughout the letters is that she’s really trying to connect with Bernadette, and is trying to seek counsel on a lot of things that are going on with her. She’s also sharing a lot of what she’s doing in her daily life, and in her work, in a way that she does to some degree in her journals as well: marking time, marking important events.

VÕ: I was curious about the ongoing tendency in the letters to move into a register of advice giving: they’re both asking for advice and giving advice in this way that they can’t help but do.

SNEED: Their little term in the letters for advice-giving, which they’re always kind of doing but denigrating, is “Poloniusism,” as in Polonius from Hamlet, the person who gives advice but it’s maybe unwanted advice. So they’re always kind of self-conscious of, “Here’s some advice, but maybe I shouldn’t be giving you the advice. Sorry if I’m being condescending.”

WARSH: It’s complicated, to say the least, because their relationship was pretty complicated. But I think the letters gave them a space in which to care for each other, in ways that maybe weren’t possible or were difficult in other places and times and spaces. But this intimacy was not easy for them and that’s part of why they’re being a bit self-conscious about giving advice, trying not to be what might be perceived by the other as overbearing, or too motherly, even. A lot of it stems from their losses early in life, and they talk about that very frankly in these letters as well, in ways that, to be honest, in real life I never heard them talk about. So, I do think it’s safe to say that they are kind of working out a way in which they can be intimate and care for each other, through these letters.

I think the closeness also has a lot to do with Bernadette having a family. Thinking about: well, what does it mean to be in a family, and what is a family? When I was born, there was this other person that then Rosemary’s a part of. And I think there’s a lot of intimacy created out of that experience as well.

SNEED: She loved you kids. All the letters are like, “Send me news of the children! What are they doing? Let me send some art for the kids.” It’s really touching.

WARSH: As evidenced by the rest of our lives, spending a lot of time with Rosemary as older children and then as adults, yeah, me, and my sister and brother were very important to her.

But I also felt there was this broader value to them discussing all the things they were working on, in what was for both of them not just their most prolific periods, but their most intense periods, when they were working on their best-known works. Bernadette talks about working on Midwinter Day. Rosemary’s working on all sorts of things, particularly some of these artist’s books that she was really focused on. So, I think the letters provide a lot of insight also into the things they were working on, that isn’t found anywhere else.

VÕ: I wonder if you could speak to how these letters act as modes of self-representation?

SNEED: For me, self-representation, when you’re in a certain scene, and you’re in the public spaces of that scene—whether it’s a poetry reading, or an art opening—there’s your face that you put on for the scene. But what we’re seeing is behind-the-scenes. I don’t think that there are pretensions there. They’re very honest about their aspirations and ambitions, you know? Like, “I’m a great writer. Is it wrong for me to say that?” Or, “I really deserve the attention in the art world that I’m not getting.” So I think that they’re super honest, and that they’re presenting their real selves, their authentic selves.

WARSH: I think that is accurate—but I think they are working through who they are as artists as public figures, too. And it’s exactly in the way that Gillian is talking about, with Rosemary struggling with the public aspect of being an artist. What’s so different for Bernadette is that she’s living in this small town in Massachusetts, where the public aspect of being a poet is virtually non-existent. Bernadette and Lewis [Warsh] are working hard on all these different projects, together and separately, and then occasionally they go to New York City for a book party, or a reading. Their social worlds are very different, and I think it causes Bernadette to reflect on how that affects one’s self-representation.

It is funny, because in Rosemary’s journal, she does talk about, “Is someone someday going to read this?” You wonder, sometimes: are they writing for people other than themselves? At some point in the 1970s, Lewis had sold some of his letters to an archive. Even at that time, it was a way for poets to make some money. Lewis also publishes The Maharajah’s Son in 1977, during this period, which is a collection of old letters that had been written to him in the 1960s by old friends and one of his girlfriends, and some of the people in the letters were upset about that. So, there are some references in the letters to the idea of making intimate letters public, and what does that mean? Bernadette even says, “Are you going to stop writing letters to me because Lewis sold some of his?” [laughs]

I feel like that’s interesting to think about too, when you’re even a little conscious that these letters might become something that someday other people read, too—does that shift how you’re telling these stories? I don’t think that it did, but… it is funny, because here we are, talking about the publication of these letters, and what it means that they are now being read by all these people.

Bernadette was definitely very excited about this project, and about sharing them. She enjoyed re-reading some of her letters and was making fun of how long and dense some of them are. “I can’t believe I wrote this way,” that kind of thing. But she also did appreciate them as part of her writing, too. [Another book of BM’s correspondence, All This Thinking: The Correspondence of Bernadette Mayer and Clark Coolidge, was released by University of New Mexico Press in December, 2022.]

VÕ: Going back to what we were talking about before: when Bernadette was writing a letter poised to be included in a larger project, like with The Desires of Mothers, that’s a particular process and tone that enables a certain sort of writing. But, even though the context is so different, I feel like another separate form of writing is enabled by the specificity and the focus of the writing being a personal thing between Rosemary and Bernadette. There’s a certain openness: for example, an ability to not necessarily finish all their thoughts, but still feel like they’re communicating.

SNEED: What you’re saying makes me think about—particularly with “The Vanity of Mount Hunger,” the letter from 1979 which ends up being published in The Desires of Mothers—there’s a mode of address there that’s so intimate and personal, but it’s like there’s two audiences imagined. There’s the immediate audience, which is Rosemary, so it’s personal and intimate: not finishing all the thoughts, there’s a flow with a rhythm that crescendos with this intensity towards the middle. Then I think that, in the back of her mind, there’s a broader audience, too. When I read that letter, I thought, “Oh my god, this is a poem!” And then when we realized it was actually a published poem, she had taken it straight from the letter to publishing it, I was like, okay: this is the one that shows the way in which the letter writing is directly informing the poetry. And with Midwinter Day as well, the style of writing, to me, has a lot of resonance with how she was writing letters.

Then there’s one letter that she wrote to fifteen people. It’s like a form letter, a conceptual project —she wrote it, and then sent it to fifteen people, and Rosemary was one of the recipients of it. So, she was definitely thinking about letter writing as a form that could then be transposed to other kinds of audiences, or rethought conceptually.

WARSH: I love the way “The Vanity of Mount Hunger” ends, because she really explains herself, and this place between letter and poem, when she says: “I wrote this for you,” so it’s for Rosemary, but then it’s something more. She says, “sort of a letter…” (so it’s not totally a letter) “…mixing together more direct love that’s briefer said…” (which I think also is getting at their relationship) “…and all the rest of everything, views and names and stuff.” Then, she explains, “That’s why it has a title.”

It’s pretty amazing, right? And sort of sums up, I think, a lot of what we’re talking about, in terms of how the letters related to her writing. It reminds me a lot of Midwinter Day, too, in the way that she’s describing this place she just moved to, and the landscape. It’s about summing up the essence of this new place, and her grappling with what this new place was, and what is her relationship to it.

SNEED: The context of this is 1979: she had just moved to Henniker, New Hampshire, where she got a teaching job at New England College. She is pregnant with Max. So, Rosemary had asked, “What’s it like there? What’s your teaching like?” And instead of just a rote, like, “Oh, teaching’s going okay,” instead, she responds with this collage of images, and names, and places. She’s capturing the ambience of this little New England town and it brings you there. It talks about the New Hampshire accent, and how that compares to the Massachusetts accent. Literary references, and Native American references to the place, descriptions of the college, and what the students are like. It’s very evocative. It brings you to the place in this ongoing flow, it’s like: idea, idea, idea. It’s this form of address that’s weaving in and out of references. It’s a brilliant response to the question, “What’s it like there, and how are you settling in?” [laughs]

VÕ: From both sides, there seems to be a particular desire to hear about the context that the other is living in. Bernadette is often asking for news from New York, particularly when she says, “Send me anything that anyone’s saying about my writing.” And then, again, thinking about Rosemary asking about the kids, and the family, and getting that context. That’s one thing that strikes me: this ongoing exchange of requests for the social contexts that they are both a part of, and yet each have some distance from at that moment.

SNEED: They’re both longing for what the other has, I think. Bernadette’s yearning for the New York scene’s hubbub, culture, and activity, and Rosemary’s yearning for family and nature and more quiet space, less stress of the city. Part of that is, they’re yearning to hear what the other is experiencing to kind of, you know, have contact with that.

VÕ: Are there moments that you all were particularly excited to share from across The Letters? Which moments leave resonance for you all, after this project?

SNEED: The “Vanity of Mount Hunger” letter was a big one for me, I think it’s my favorite one. And some of the art gossip, [laughs] and art critiques, like, “I went to this show, it was really good. I went to that show, it was horrible.” That stuff, for me as an art historian, I just find those tidbits so satisfying.

WARSH: I have both historical and personal interests in these letters. Having been working on understanding Rosemary’s work, and what she was trying to do in this period, I was really struck by the way she talks about some of her projects, what she’s working on, and some of the shows she’s having. There are a lot of great clues as to what she was doing and how and why in these letters—those are helpful to me as I’m thinking about presenting some of that work again, and doing so, obviously, without Rosemary being around. So, for me, it’s always very helpful to have her insight and her words describing her work and why she’s doing it and what it means for her.

Similarly, there’s so much great insight into some of the things that both Bernadette and Lewis were working on at the time. Talking about Midwinter Day, talking about their collaborative book Piece of Cake, talking about starting United Artists magazine. All those details are really interesting, and I think of value to those who are thinking about Bernadette and Lewis and their work.

And then of course this is another installment in my incredibly well-documented childhood! [laughs] It’s fascinating to hear about the things that I was doing as a baby and small person. When we did the reading yesterday, I had chosen four exchanges, one from each year, ‘76 through ‘79. Hearing this sort of capsule version of The Letters, what was fascinating was that I am growing up through the letters. In the course of four years, I talk more, I’m starting to read, I have a friend, and I started out as a small baby only saying one word.

So, yeah, I always really enjoy those details, from a personal perspective. And also the way in which Bernadette was really fascinated by raising children, and enjoyed it, and how that became so integrated into the things she’s writing and thinking about. That becomes clear in a lot of her poetry, and you also see that here.

SNEED: And I would add, it seems like right now is a moment in which there’s a lot of discourse around the role of motherhood in relation to being an artist. When I interviewed Rosemary in 2013, I was pregnant, and I had my child not too long before she passed away. So, for my whole trajectory of researching and writing about her work, and working on The Letters, I’ve been a mother raising a small child. And I have to say, I deeply identified with so much of what Bernadette is talking about. She was charting how she’s going to balance doing her writing and being an artist while raising her kids, and both her fascination and her abundant love for her children, but also her ambivalence sometimes about navigating these things, and also trying to balance things with her partner. My partner is an artist, so my life was just mimicking exactly some of the things she was talking about, and I found it such a comfort. I just super-connected with that, and I think many women who are mothers, and also who are not mothers—women who are artists, or writers, or who have careers in New York—will relate so much to these letters. To me, that’s just really amazing, that something that’s over 40 years old could still feel so completely relevant, and something that I think readers will absolutely connect with.

___

9/25/79

Dear Rosemary

THE VANITY OF MOUNT HUNGER, a letter?

___

We have mount hunger and mount misery here, I guess it all has to do with the poor pioneers, we have enough money for once but not enough time, there’s too much happening all the time and at the same time too little, if we buy paper for the magazine we see we can’t pay our bills but we have plenty to eat. Some families are just nervous like epochal letters, the Howes are a nervous family, I met Susan and now I’ve met Fanny, their mother is a woman named Mary Manning who ran the Abbey Theater and Fanny’s father was a radical lawyer, can you imagine coming from a family like that? We’re a nervous family too I guess though it’s more anomalous to have emerged from the saintly stodgy Germans with nothing to do with that, no tragedy or drama like the Irish people and thus no fragility among our nerves. Sometimes it seems our nerves are not continuous like the nerves of others but simply either absent or deadly as if there were, always possibly available, a state of perfection we could have, do you know what I mean? How come you aren’t writing, I mean letters. In the midst of all this change it makes me feel disconnected to you, is it the result of so much isolation this summer or just gearing up for the cold weather’s work, I feel kind of staid tonight. And fat, I can feel the baby moving, we’ve been eating a lot, a lot of fish, isn’t that what rich people eat. The kind of time I need I haven’t had yet here, it’s a kind of absent time, probably what you’ve been having, where I can do something or nothing but without having to think the way you think when you have to do something else next. I like having nothing I have to do, that’s why I liked Lenox, I tried to explain to my class today what I felt about the word “Henniker” and it turns out there’s a Dutch word, there’s a Dutch woman in the class and the word is “Henneken” and it means the kind of noise a horse makes when it titters repeatedly like a form of neighing kind of the way you might describe the laugh of a silly girl. Interestingly, this woman’s name is Flora, Flora Soffree. Sophia’s new name, made by Marie, is Sophia Fifi Sunflower and now Marie’s decided that this is a family of Fifi Sunflowers and we all have to have that name in back of ours though she calls herself Marie Ray Fifi Sunbeam. Those two are beginning to have a secret language and when one of them says a certain word, and one of the favorites is “tedemone,” when one of them says it the other one has to say, “don’t say tedemone!” and that’s how the game goes. Sophia can say everything now (if I forgot to tell you tedemone is the name of a game, another game where each them wraps herself in a baby blanket and sort of skims about the house as if she were on ice skates pretending they’re kings and shouting “tedemone, tedemone” and so on), she can even say, “I’m hungry, I want breakfast, but first a diaper change.” Meanwhile, down the road, in a field above a house at the corner of Gulf Road and Flanders Road where they meet with Ramsdell Road which is the road that goes along the river, the Contoocook, a big wide healthy river that curves around in circles all over this place and runs right in back of the main street of the town of Henniker and many other towns around here with endless dams and bridges because of it, covered bridges even, numbered covered bridges, this river is a whole civilization, and at that intersection of roads in that field are three llamas. Marie had been saying for days she was seeing llamas, just the way she used to say she saw monkeys on the windshield of the car when she was a baby, then we saw them too, two big ones, a white one and a brownish one, and one little one. Do you think that living in Henniker will mean after all we’ll get to drink llama’s milk? And llama cheese, cream and all the rest! Llama curds and whey! A field of llamas, sometimes they run. What geniuses the people who keep them must be, to have known we were coming and would see them. A source of wool, meat and milk. I think what I’ll say when I ask at the drugstore, the center of life here, who it is who owns the llamas, who has them and they say, like everybody says about words in Henniker, what is that? A llama is a mammalian animal much like a camel but without any humps. A llama for us or above us, is life really too simple or too free, is it a sin to see a llama. I still haven’t entirely ceased the smoking I began again when we started to move but now I’m smoking something called Triumphs (llamas) that have practically nothing in them and you can’t drink beer anymore, now beer causes cancer too, but strangely according to the information given, not Guinness Stout. It was Lea whose real name is Leona who turned me on to Triumphs, she’s Russell’s daughter and when we were in Boston last weekend Russell kept saying he had found some mini Guinneys, meaning little stouts (little llamas, babies, writing poetry has always been so much like love). Around here in the neighborhood is the Converse All-Star Factory and did you read about the woman Ann Meyers who was the first woman to be drafted by the NBA (basketball), she didn’t make the team (they drafted more players at the outset than they need and then get them down to eleven) and some people said it was done for publicity and sometimes it was kind of sad, people’s hideous remarks, it was brave of her, the players didn’t talk against her just the managements and sportswriters, it was inspiring too and then in the pictures of her at practice with the team you saw and you instantly realized you should’ve thought of it before, that under her normal uniform (the undershirt-like shirt and shorts), she had to wear a short-sleeved shirt, to be modest. Now if you ask me I can’t even remember what the women’s college team wear, and otherwise in some way she looked like a very serious man and I admired her, and wished I could be her. These pants I’m wearing right now, which Lewis’s mother got me at Lady Madonna’s in Pittsfield (that’s one of those hip maternity places) were not made for a skinny person who has a normal baby, you’re not supposed to be skinny and get really big with child, you’re just supposed to become all-around fat and so the pants, as the baby grows, are getting too tight, there’s room for me but not for the baby at all. The woman who sold us these pants told us when you’re pregnant you’re supposed to look awful and puffy and ugly and wear baggy trousers that make you want to commit suicide, maybe so you won’t want to dance. Like llamas? We bought a case of wine with our salaries in Boston, it’s called Dahra, from Algeria, very cheap, there’s no good wine in Henniker, do you know which Concord the Concord grape is supposed to come from? Is it Concord, N.H. or Concord Mass or Concord somewhere else? Around the outside of the house millions of grapes are growing, not even all ripe yet, and pear trees hung with big pears that are still hard, this slow and sunless New England, I was told I could harvest the pears and make pear jelly, why not, if they have llamas here.… Kerouac says a wonderful thing on the first page of VANITY OF DULUOZ, he says (after he addresses his wife to whom the book is dedicated, as “wifey”) you guys never liked my dashes at all so I’ll punctuate for you. Sometimes I think being here teaching where nobody knows anything will make us forget what everybody knows and we will begin to have to say, out of habit, the simplest things in the simplest ways, even in our poems, what would happen then? The New Hampshire accent is less an accent than quick talking in a certain tone of voice, you say a lot of things in a hurry, maybe about the weather or freezing in low sort of growling tones, not bad tones, but laconic and succinct and sufficiently slurred to be alarming, and then you stop and be quiet. It’s different from Massachusetts with its yawning a’s gotten from upstate New York. And they don’t call them cheeseburgs here, they leave the “er” on. On our way back from Boston we went to see the ocean at this place called Plum Island and we passed over where the Merrimack River runs into the sea, that’s the river that runs through Concord and Lowell, Kerouac’s river. I read his new biography but I see very quickly I’d better stop speaking so incessantly of him, Kerouac, Shakespeare, Bernadette, they’re colorful names in a similar way. There was something funny in the biography, this guy who wrote it said he thought Kerouac was going off the deep end for thinking he was such a great writer and saying so, just like they always say Stein was a megalomaniac. It seems like they were that great, Kerouac loved Proust and Shakespeare and started reading Henry IV outloud with somebody and then the other person realized he was doing it from memory, and he liked Stein too to some extent, what is wrong, inaccurate, inappropriate or bad with their understanding of that? The knowing that they were great, and still alive! Poor old Kerouac died early anyway, in 1969 while I was living in great Barrington and I thought I should’ve gone to his funeral in Lowell, but I didn’t dare. So I’m up here with them, Hawthorne was here too of course and wrote three stories about the White Mountains the foothills of which I am in, one was “The Great Stone Face” about the Old Man of the Mountains, and the others “The Ambitious Guest” and “The Great Carbuncle,” all about that part of the mountains around Franconia I wrote you about, where we were. The Indians around here were fishermen who found jasper, a reddish kind of quartz, for their tools, and Contoocook, Penacook and Suncook are places in the local phone book, along with the ordinary English Chichesters, Pittsfields and Washingtons, and even a Bow and a Waterloo. A famous woman photographer lives in Dearing and there’s a town called Hooksett. Marie has poison ivy but for some reason she never scratched it so it never spread, it exists as these peculiar bumps on her legs and she says her ass itches and would I scratch that for her as she can’t get at it with her sleeping suit on. It’s been cold, I wonder sometimes how much to tell, have I really seen as much as I feel like I’ve seen even without really traveling but just moving occasionally from place to place in order to be able to live o.k. or make some money, maybe it’s our duty to be as derelict as Kerouac and just as fast, fast even faster to the scene of the disaster. It’s funny being a painter you don’t exactly have to feel that way, about seeing everything, do you actually wind up hearing most of it like Gertrude Stein was saying, about Picasso? And then you can paint it or make it? She even cut off her hearing of American so she could write it, idiosyncratically. Now I have to sell it to these students who kind of lounge in the grass while I try to tell them things, it’s what they call a party school only skiing seems to be replacing basket-weaving, no I shouldn’t say that, it’s just that you can’t tell where you are and what is writing, that’s the trouble with paying people to do certain things, maybe the cold weather will spruce up all this. After the last ice age began to diminish in New Hampshire, first the hills were bare, only sand, all brown all winter, then tundra rushing, the treeless plains of the arctic regions with birch trees on them, these beautiful birches that are now adjoining the barn in such perfect adherence to form as we learned about it, then the pines and evergreens which grow here like endless drinks in a bar, then the rest of the deciduous trees, all the varieties but of course mostly the maples which hang over the house with grace, brushing against everything. Here the apple trees were planted and the other fruits and grape vines around the barn in such a way as to make you want to weep for necessity, its former orderliness and the use of everything even in a climate like this one in the overgrown fields we now look around in where someone who never thought we’d move in here all of a sudden, renting half a house from a psychiatrist, arranged all this. Our culture is more in between the store and the wilderness all this has become, and in keeping a car, no horses in the barn, no milk either, old weathering sleighs in the field, old boards to play on, paths between stone walls, a lot of stones to make them with. Were the people who made all this and put it together plagued with as many wasps and bees as we are this year? And crickets, overwhelming us, now beginning to dissipate and make room for the winter birds. Will the field mice and flying squirrels move in? The landlord, this psychiatrist who’s never here, who’s reoccupied this place, gets Playboy. And he is shrill but luckily liberally tolerant at least of us. I can notice the slightest difference in the fever of the room, fever of the field, it notices me. You can sit on the porch which has a screen on top, a sort of ceiling, and look at stars. I wrote this for you, sort of a letter mixing together more direct love that’s briefer said, and all the rest of everything, views and names and stuff, that’s why it has a title.

Love,

Bernadette