This post is part of an ongoing series of writing about the VHS Archives working group, which is devoted to the use, preservation, digitization, and research of VHS collections currently held by organizations, scholars, artists, and activists. This working group is supported by the Seminar on Public Engagement and Collaborative Research.

Jaime Shearn Coan

August 8, 2018

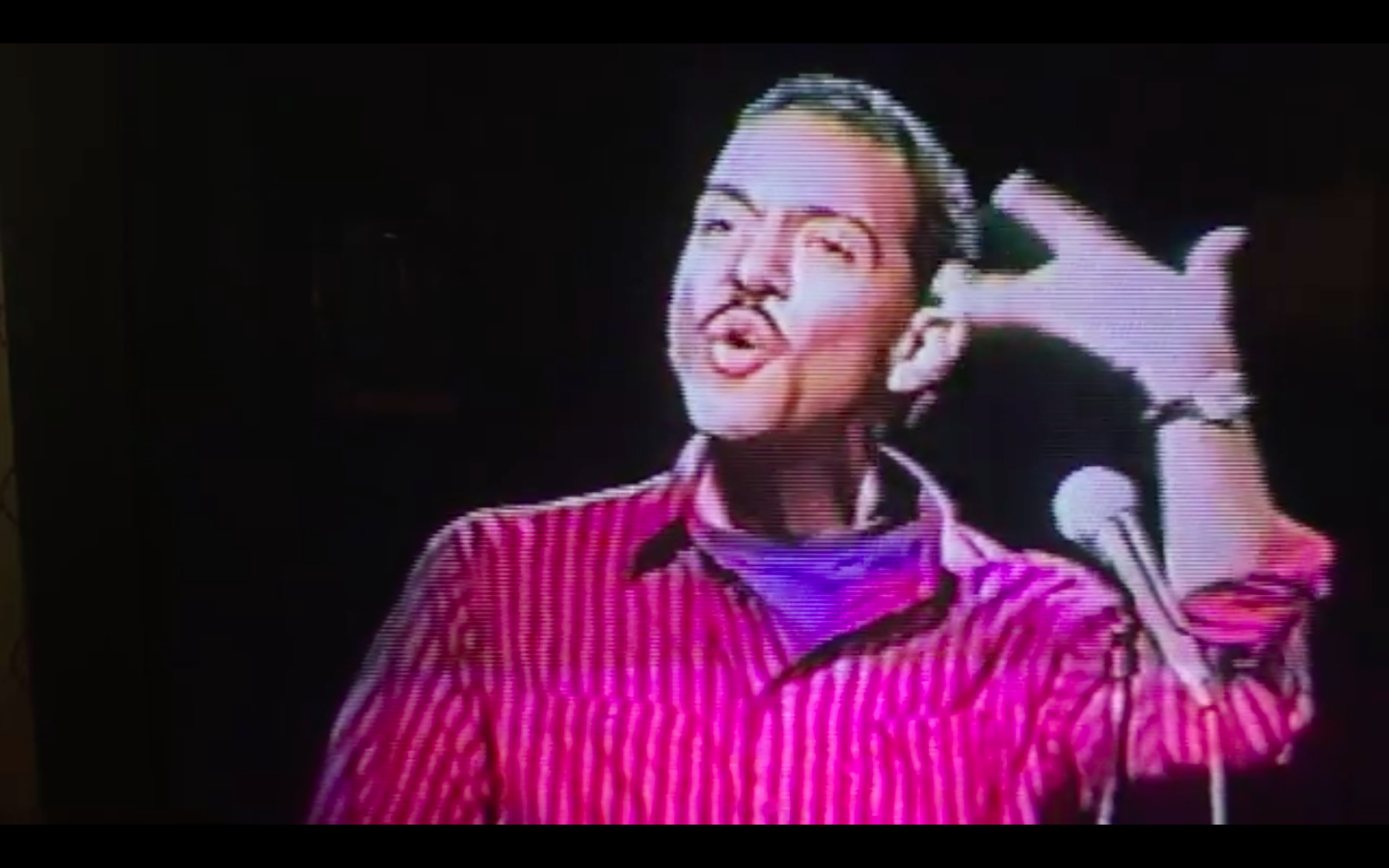

The image you see above is a screenshot I took of an episode of the talk show Donahue from February 13, 1990, in which five members of ACT UP (Peter Cramer, Mark Harrington, Peter Staley, Ann Northrup, and Robert Garcia) appeared shortly after of the controversial Stop the Church action at St. Patrick’s Cathedral (December 10, 1989). During the course of the show, the ACT UP members struggle to quickly and effectively provide corrective information around HIV/AIDS, defend PWAs (People With AIDS) and the tactics of ACT UP, as they are interrupted and cut off—by Phil Donahue (an epic mansplainer), audience members, and each other. The opening of the episode shows footage from St. Patrick’s, and more protest and related media coverage is interspersed throughout. Toll-free hotline numbers and a mailing address for ACT UP flash across the screen. Members of the audience offer very pointed and polarized opinions, including advocating for quarantine and intimating that ACT UP members were on their way to becoming terrorists.

Thanks to SuchIsLifeVideos, this archive of public opinion is available on YouTube. I came across the uploaded material, most likely taped off of a television set, while looking for video footage of Robert Garcia (1962-1993), a key member of ACT UP who, in 1988, co-founded its Majority Action Committee, which focused its energies on working within POC communities affected by HIV/AIDS. The first comment listed below the video is from Lorraine Garcia, Robert’s sister, in 2015. She expresses thanks for the video being made public, and calls attention to ongoing struggles related to HIV/AIDS before concluding: “My brother passed away in CA surrounded by family on May 13, 1993 a short three years after the show aired. My parents will watch this video with good memories.” Reading this, I was struck by the many layers of public and private at play in the life of this media object. While it was easy enough to access this episode in 1990; if not recorded privately, off the TV, it entered into a less accessible world of storage. With the material being reintroduced into public circulation via YouTube, it becomes available to publics, but also to the private spheres of friends and family—in the context of HIV/AIDS, this allows those who survived to see and hear those who didn’t.

Robert Garcia’s papers, including an extensive video collection, are held at Cornell University. They were organized by his close friend Karen Ramspacher, an artist, activist and educator herself (member of Group Material). I have had the occasion to view them there, but how many people who knew and loved Robert, including his family of origin, but also friends, lovers, and fellow organizers have made it to that library high up on a hill, badge in hand. Beyond that, thinking intergenerationally, how many younger people who might benefit from Robert’s legacy are not even aware that that legacy is painstakingly preserved? In my post-archive searches to find clips of Robert that I could share with others, I was surprised to find another video of Robert online, posted by Cornell University Library, oddly as part of a digital exhibit on the history of the Human Rights Campaign (HRC). I hadn’t viewed or known about it in the archive. It was especially exciting because it was a full recording of a class visit by Robert and Karen Ramspacher—to a CUNY campus: John Jay College, Spring 1991. In the video, Robert and Karen perch themselves on a desk in front of a blackboard and talk frankly about HIV/AIDS and their organizing work. I’m not aware of whose class this was, who invited them, but it seems to be that this is a record that the CUNY community should claim and circulate, as just one example among so many of socially-engaged pedagogy.

+++

The VHS Archives Working Group meeting on Wednesday, February 7, 2018 was focused on methodological questions related to working with VHS archives. I showed the above-mentioned clips, along with some others, and was joined by Shanti Avirgan, a media maker, researcher, and educator who presented on her current role as an archival producer on a mainstream film about HIV/AIDS. Also present at the meeting were Alex Juhasz, Jean Carlomusto, Rachel Mattson, Lisa Cohen, and Ann Matsucchi.

Shanti’s presentation engaged the “methodological and ethical challenges of finding, accessing and bringing back into circulation TV news footage from the early days of the epidemic.” After working on independent film projects including the documentaryPills, Profits, Protest (2005) and the HBO documentaryLarry Kramer in Love & Anger with Jean Carlomusto, a longtime AIDS media activist, she was now working on a new big-budget film project about the nurses who created the first inpatient AIDS ward at San Francisco General Hospital. As archival producer for the film, she needed to obtain mainstream media coverage, which meant that she needed to work with local news channels with often very unorganized tape storage rather than institutional archives; she also had to figure out how to get into those spaces and establish connections to people inside of those spaces who cared about the project, since there was no imperative for a news network to provide materials. In addition, Shanti combed through materials that were available online, such as The AIDS Tapes collection, curated by Michael Aldrich on the digital library site Internet Archive. Shanti and others spoke about the ethical concerns of recirculating images of suffering, which, Alex pointed out, early AIDS media activism sought to limit, replacing pathological and morbid depictions of PWAs with images of empowerment.

In her 2006 essay, “Video Remains: Nostalgia, Technology, and Queer Archive Activism,” a companion piece to her experimental documentary film of the same name, Alex Juhasz proposes “queer archive activism” as a practice that, unlike a nostalgic desire that wants to fix images in time, or to reach endlessly towards a vanished past, can instead “relodge those frozen memories in contemporary contexts so that they, and perhaps we, can be reanimated” (320). Regarding the project that Juhasz undertakes, she is the owner and steward of the 1992 interview with her close friend Jim Lamb that is featured in her film. In Shanti’s case, she is aligned with a very well-financed project. How might those of us who do not “own” or cannot purchase or share the archives that we work with do the work of recirculating and resituating materials in order to create new meaning in the present? And is it possible to reintroduce the cultural work of our archival subjects when there aren’t many video materials available?

This is a question that came up during my presentation, as I expressed frustration at the lack of performance documentation available in my dissertation research of the work of the poet, editor, publisher, theater maker, performance artist, musician, and outspoken HIV-positive activist Assotto Saint (1957-1994). Footage of his own theater productions, his own artistic vision, remains elusive, unavailable. I showed the group screenshots that I snapped from HIV/AIDS-related documentaries and experimental films that Assotto appeared in, falong with a few short clips that are uploaded to a Facebook page dedicated to his memory. In the videos, Assotto reads poems by Melvin Dixon at what appears to be a memorial event, including “The Children in the Life.” After watching the clips a few times, I noticed that the edge of a TV set is visible on the left side, and a small strip of wall, perhaps covered in wallpaper, appeared behind it. A hand held a camera to that screen in order to catch a fleeting broadcast of a friend. That hand then made it available to others through social media, preventing its moldy end in a basement somewhere by digitizing it, circumventing archival repositories in order to share it (somewhat) freely.

After the screening, a (friendly) debate ensued over whether video documentation is the most authentic, and therefore most valuable, vehicle to carry the legacy of a performing artist into the future. This conversation helped me to consider other methodologies, such as oral history, that might reanimate, to use Juhasz’s word, the experience of the performance or the embodiment of a person, in a way that video might not be able to achieve. That said, the systemic inequities that have resulted in great voids in performance documentation in the archive, especially by HIV-positive LGBTQ artists of color, need to be addressed in order to prevent ongoing erasure; Although technologies have changed, and recording is no longer as difficult, the priorities of institutional archives also have to shift, to ensure that digital materials from marginalized communities stick around.

+++

Two months later, on April 11th, 2018, the working group reconvened, again taking up, from different locations, the circulation of VHS archives, particularly related to queer cultural production and the impact of HIV/AIDS. In the first presentation, Lisa Cohen shared from a work-in-progress that is engaging the archives—video and textual—of her friend James (Jim) Lyons, who died of AIDS-related causes in 2007, at age 46. Jim was a fixture of New Queer Cinema and other independent filmmaking, working primarily as a film editor, but also as an actor and writer, collaborating with Todd Haynes and others. Lisa spoke about Lyons’ life and career, and about the relative invisibility of film editors’ work. She showed some clips from an unfinished video project that he shot in Hi8, which she had recently had digitized (after consulting with Rachel Mattson), enabling her to watch the tapes for the first time. They consist of almost 8 hours of interviews Lyons conducted in the early 1990s with a former lover, who was living with AIDS in San Francisco. She directed us to some of the visual and verbal traces of Jim himself that she found in the footage, and found meaningful. She finished by talking about his “interrogative voice” and by reading us a litany of some of the questions that he asked on these tapes and that he wrote in his journals—questions for this former lover, for himself, and for his doctors—about mortality, AIDS, and embodiment. Because she and Jim were close friends, Lisa’s project is intimate and intersubjective—friendship is revealed to be not limited to the making of the archive, as in the case of Karen and Robert, but in the processing and making sense of it, too.

For the second presentation of the evening, Rachel Mattson delivered a meta-presentation of a presentation that she has given on a few occasions and which continues to evolve, titled “tenderness in the face of (the magnetic media) crisis…and other archival dilemmas.” Rachel provided some really useful history on the development and wide-spread adoption of hand-held recording equipment and provided a framework which could help us to understand the crisis of “degralescence” (a term that combines the words degradation and obsolescence, coined by Mike Casey). She stressed how much of the material recorded on magnetic media archives the work of community activist and artistic groups, and chronicles queer culture-making, and emphasized what a loss it would be to lose that material. She drew parallels between the precarious nature of queer life, its documentation and the precarious nature of magnetic media, and offered “post-custodial archival strategies” that could help to ensure sustainable storage and access. She showed us clips of recently archived material from La MaMa, which showcased queer theatrical performances including “Three Drag Queens from Daytona,” starring Jimmy Wigfall, William Duffy, and Peter Bartlett (1973) and another clip from 1973, which showed Candy Darling delivering a monologue during a bilingual theater production by Duo Theater. I had never seen her in motion before, effortlessly handling a crowd, only frozen in Hujar’s iconic photograph, “Candy Darling on her Deathbed.”

+++

A rotating cast of members has participated in this working group over the course of the year—each session it always felt that the right people were there. At the February session where I presented my work, it was a very small group, and I felt exceedingly lucky. I was surrounded by mentors, instrumental activists and media-makers and writers and archivists who strove to both document and intervene in representation, women who cared for and fought for their queer male friends in life and beyond death, while also advocating for the underserved and under-recognized women living with and affected by HIV/AIDS. When I finished my presentation, Jean Carlomusto immediately told me that she had footage of Assotto, and that she would send it to me. She also offered to put me in touch with Karen Ramspacher, Robert Garcia’s best friend, and asked me what I would ask her if I spoke to her. While I paused, somewhat flustered, Rachel Mattson jumped in and said that she would want to know the narrative of how Robert’s archive was put together. We all nodded enthusiastically, mutually excited by the possibilities so close to hand, the connections lying just under the surface, the small acts of generosity that aim towards something larger, something beyond us. Archives are everywhere people are.

References

Alexandra Juhasz, “Video Remains: Technology, and Queer Archive Activism.” GLQ 12:2 (2006) 319-328.