My Planning Fellowship with the 2018 Reclaimed Lands Conference

Christine Stoddard

It’s been a long time since I participated in a science fair. But when I applied for a planning fellowship with the 2018 Reclaimed Lands Conference, I knew I wasn’t signing up for any old science fair. As an M.F.A. student in Digital & Interdisciplinary Art Practice, I consider myself an artist first, but I’ve always had a strong interest in science, specially ecology and biology. This fellowship allowed me to build up my experience as a curator and designer who cares about the environment and wants to work with scientists. It also gave me a chance to be a part of a science fair again—or at least an event with a science fair element. The Reclaimed Lands Conference was not just an event for art or science; it was an event that united practitioners from a variety of fields, making it the first-ever interdisciplinary research conference hosted by the Freshkills Park Alliance of NYC Parks.

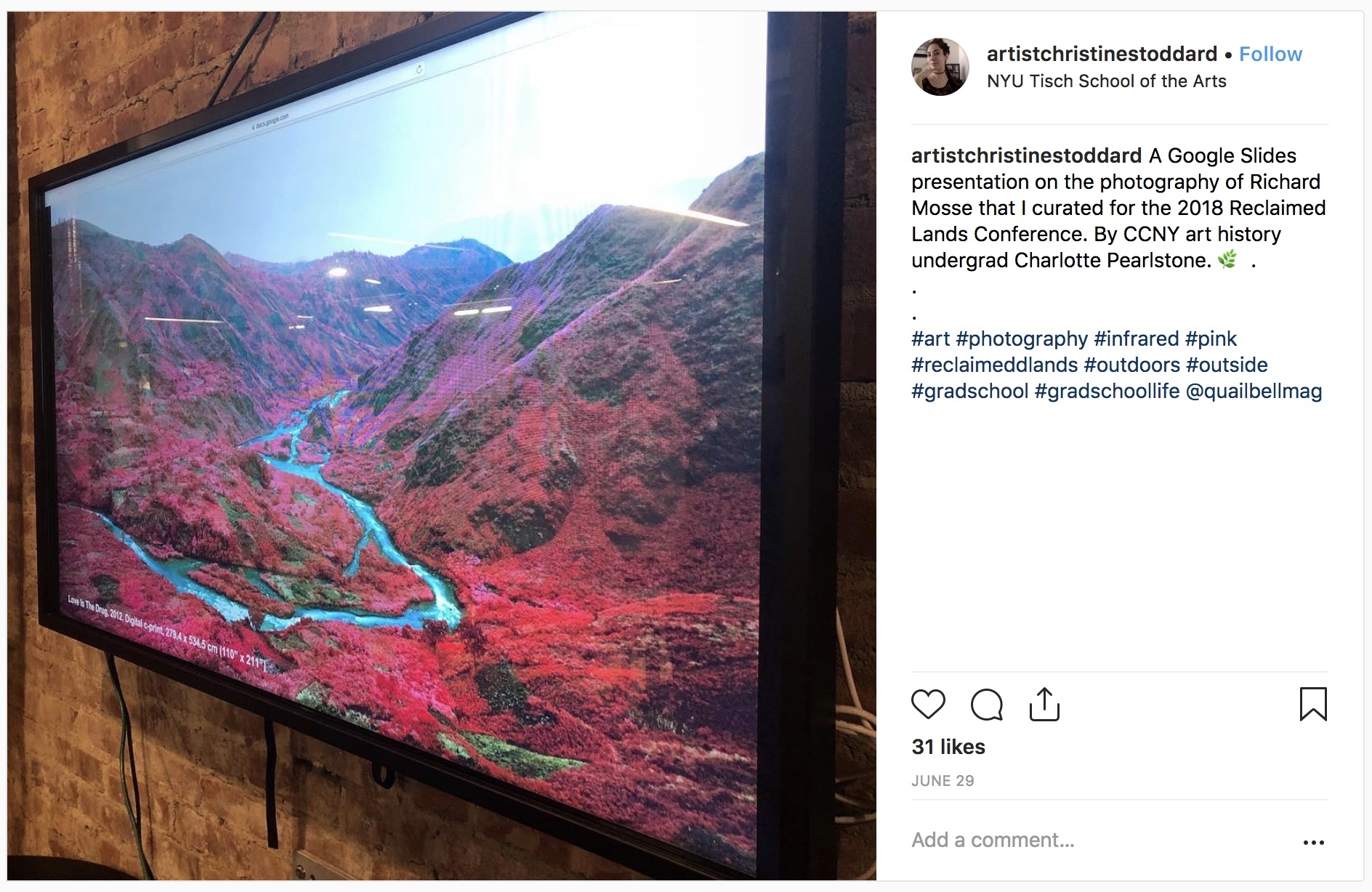

Fresh Kills Landfill was once the largest landfill in the world. Now the site is on the path to becoming a world-class park on Staten Island. With 30 more years to go before the park opens on a daily basis, the Freshkills team is using the area for scientific research, art projects, and educational purposes. It is a prime example of how scientists and artists can come together for the common good. That made it an ideal centerpiece for the Reclaimed Lands Conference, which took place at NYU ITP and included field trips to Freshkills, Brooklyn Bridge Park, Liberty State Park, and Penn & Fountain Ave. Landfills. While science was at the core of the conference, artists, architects, and urban planners also presented their projects and took part in panel discussions. My role was to help Dr. Cait Field, the director of scientific research at Freshkills, plan and execute the conference. By the time I started in April, conference planning had already been going on for more than a year. Still, there was much work to be done for the conference set in late June. I did everything from curating a 12-screen video installation to designing the 20-page conference program to hanging up panelists’ scientific posters and more.

Changing perceptions was one of the panel session topics because there are many assumptions people make about sites that once housed factories, landfills, railroads, and other industrial facilities. On the pessimistic side of things, people may think a land site can never recover from these activities because they have a very narrow idea of what recovery looks like. They may see these sites as forever damaged and unsafe for humans and pets. They may think these sites are ugly, smelly, or otherwise unpleasant and can never be used for recreational or educational purposes. On the optimistic side of things, people may think that scientists can easily restore an industrial site to its “original” state with enough foresight and funding. As I learned from the conference, all of these perceptions are problematic for various reasons. Scientists can reclaim former industrial sites, but that reclamation can look a number of ways. Some of those outcomes may be unpredictable given current scientific understanding, especially in cases where an industrial site has no precedent. A site may have been woodland prior to industrial activity, but that does not necessarily mean it will be restored to woodland after it has been reclaimed. It may be more feasible to nurture healthy grassland there instead. There are also different definitions and degrees of safety for humans and pets. Some lands may only be safe at certain times of year or for certain activities or if visitors follow certain precautions. Then there is the matter of what a site looks like. Since beauty is subjective, what is scenic to one person may not be attractive to another. Some people may prefer the look of a meadow to a wetland without appreciating the value of the latter. These and other perceptions were among those brought up at the conference. As problems were identified, participants brainstormed possible solutions, which was the main purpose of the interdisciplinary format.

Changing public perceptions is one area in which artists and scientists can most benefit from collaboration. Environmental scientists ask questions about plants, animals, and the land. Then they seek answers through research. Artists can then come up with creative proposals for presenting this research to the public and inspiring people to think about it in new ways. Many people won’t look at data or read scientific papers, but they will watch a video, play a game, attend a concert, engage with an art work, or participate in any number of other creative activities.

Last summer, I was the artist-in-residence at Annmarie Sculpture Garden, a Smithsonian affiliate in Maryland. I proposed making 11 sculptures out of recycled materials and modeled each one on an animal native to the Chesapeake Bay area. I collaborated with the on-site naturalist to choose the animals. They weren’t necessarily the “cutest” or most beloved. One of the aims of the project was to educate people about how different species are vital to an ecosystem. Many animals species are dismissed as ugly, disgusting, or scary because people do not see their ecological value. One chance to change people’s minds was the Insectival, a festival all about why we need insects and arachnids. I already had a butterfly in progress for the event, but the naturalist suggested I also make a brown bat. Brown bats eat mosquitoes and are important pollinators in the same way that many insect species are. It was a great suggestion. The sculpture gave me a chance to talk about why we need bats in the Chesapeake Bay area. Predictably, there were people who said they didn’t like bats. They assumed that all bat species drink blood and have rabies. This public art project offered them the chance to dispel these myths and learn the facts about bats.

Freshkills Park hosts Discovery Days to educate the public and change people’s minds, too. I went to one a couple of weeks before the conference. The public had the chance to make wind chimes out of recycled materials, contribute to a community mural, watch the Staten Island Philharmonic perform, go on a bird walk with NYC Audubon, ride bikes, and more. It was only my second time at Freshkills. The first time I went was in May with Dr. Field. Despite what I read and the photos I saw, I expected the visit to be unpleasant—stinky, muddy, and unsafe. I guess in that sense, I wasn’t too different from the people who thought all bats drink blood and have rabies. Going to Freshkills completely transformed my perception. Dr. Field and I counted osprey eggs, listened for grasshopper sparrows, and took measurements for the park’s mobile science lab. The landscape was lush and green and waters sparkled. Even though Freshkills Park is located in New York City, it feels so far removed from the city—and yet it’s not. That being said, it’s not terribly accessible without a car. Part of the long-term plan for Freshkills is figuring out convenient public transportation to the site, which was discussed at the conference. It was also illustrated by the somewhat cumbersome journey we took to get to the park site. For most conference participants, it meant taking the subway or driving to the Staten Island Ferry, taking the ferry, and then taking a bus from the ferry to the site. Transportation is definitely one of the biggest barriers the Freshkills team has to overcome. Yet I’m sure that the more people come and see the park, the more “converts” they will snag. During the conference, we took a field trip there and so many people remarked on its beauty. Like me, they had no idea how gorgeous it was. Going there made it easier for them to envision its potential as a site that people will relish visiting. After all, science fairs have their limitations. Experiencing the power of interdisciplinary research and innovation in action is what will change people’s perceptions. There always remains the challenge of how to best implement environmental visions and get people to witness the results.