The Danspace Project Platform 2016: Lost and Found took place October 14 – November 19th. Co-curated by choreographers Ishmael Houston-Jones and Will Rawls, with the assistance of Judy Hussie Taylor (Executive Director and Chief Curator of Danspace Project), Lydia Bell (Program Director), and myself (Curatorial Fellow), the Platform considered the impact of the early years of the AIDS Crisis on dance communities in New York (primarily in the East Village) on multiple generations of dancemakers. It did so by taking a multifaceted approach, including performance reconstructions, newly commissioned dance works, film screenings, readings, conversations, a zine project, a vigil, and a catalogue.

As part of this programming, Janet Werther and I (with Amy Herzog and Ed Miller serving as faculty advisers) co-organized two events to take place at The Graduate Center, as a collaboration between Danspace Project and Mediating the Archive, with the intention of bringing scholars, activists, and dance community members, who might not otherwise encounter each other, into contact.

In the final moments of the closing event of the Platform, an audience member expressed gratitude for the fact that the Platform did not only what it set out to do in its mission—but that it also, inadvertently, straddled life before the election and life after it. I felt that shift acutely in the organizing of the two events; the first, Interventions in the Narrativization of HIV/AIDS, took place on October 27th, and the second, A Matter of Urgency and Agency: HIV/AIDS Now, took place on November 10th, two short days after the announcement that Donald Trump would be the next president of the United States. As I said in my opening remarks that evening: “Urgency just got a lot more urgent.”

* * *

Interventions in the Narrativization of HIV/AIDS brought together senior and junior scholars including David Román, Professor of English and American Studies, USC; Tara Burk, Art Historian, Rutgers University; Lesley Farlow, Performer, Choreographer, and Associate Professor of Theater and Dance, Trinity College; Thomas F. DeFrantz, Choreographer and Professor and Chair of African and African American Studies, Duke University; and Janet Werther, Dance Artist and PhD Student in Theatre, The Graduate Center.

At the close of my introduction that evening, I said: “I see tonight as an effort, one that joins many others, in attempting to loosen up what we think we know about the past. The idea that the past no longer touches us—that in 1996, the clouds parted and a miracle occurred, is foolish. Let us not forget or ignore the immense losses and the continued trauma that is with us still, whether we were there or not. Let us listen more and listen differently.” The first speaker of the evening, David Román, got up in front of the audience, and promptly stated: “The story of AIDS has always been one of contestation and revision.”

Román spoke of his early research on performance and activism that addressed AIDS (outside of New York and outside of ACT UP), which would result in his first book Acts of Intervention: Performance, Gay Culture, & AIDS (1998). Although he was racing, in the 90s, to document this work before people passed away (and he cited AIDS scholar Cindy Patton as influencing his understanding of the need for haste), as a first generation AIDS scholar, he acknowledged that he has helped set the narrative of AIDS history that is now being challenged.

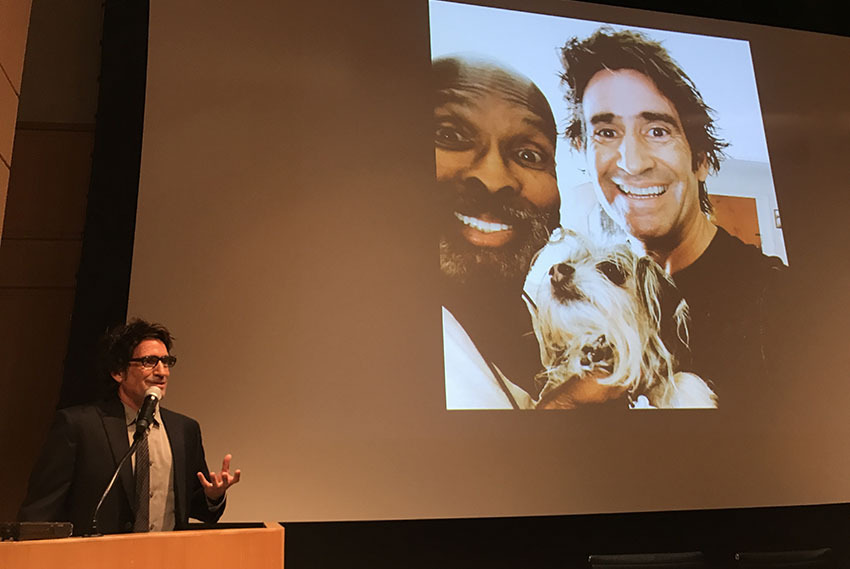

For this occasion, Román spoke about two California-based dance artists including Ron Dennis, one of the original cast members, and the only black cast member, of A Chorus Line, who tested positive for HIV in 1985.(Román also mentioned the wide orbit of people linked to A Chorus Line who died of AIDS.) Dennis moved to LA and, in the 90s, put on a one-man show about being a gay black man living with AIDS; he also got involved in AIDS advocacy and outreach. Dennis is now 72 years old and identifies as a “long-term survivor.” As Román showed us the charming photo below, he expressed concern about the isolation of queer seniors living with HIV, noting the incredulity that Dennis expressed about an audience in 2016 being interested in his story.

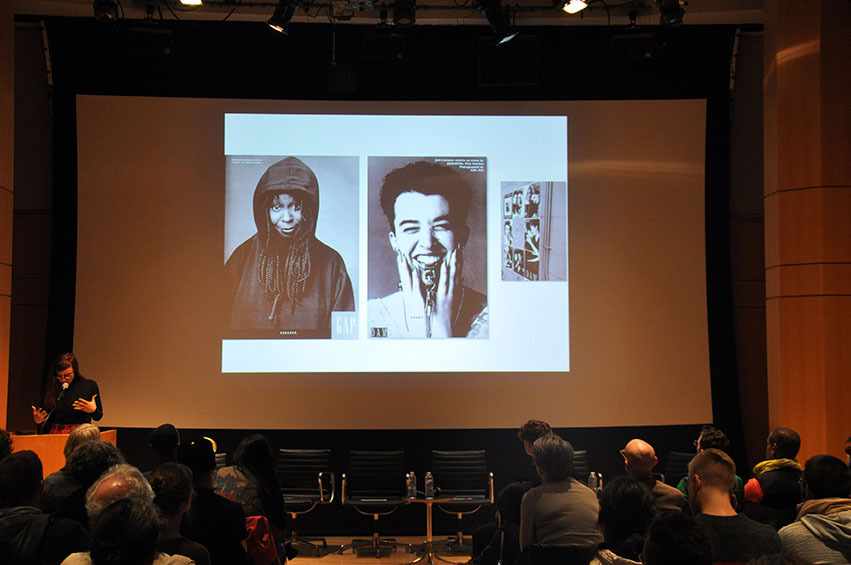

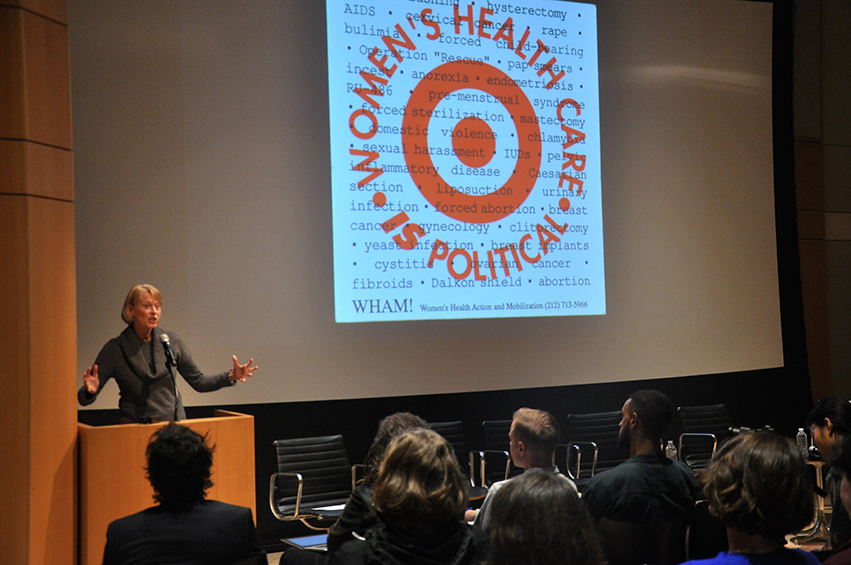

Tara Burk, a recent graduate of the Art History PhD Program at The Graduate Center, presented on her dissertation research on AIDS and queer activist posters and graphics circulated in NYC in the late 80s/early 90s. Rather than stable objects, she described these materials as “transient agents”—graphics that were worn, carried, and affixed to city surfaces. She also mentioned that these graphics have afterlives—this made me think about the graphic we chose for the poster for the event: a flyer from WHAM! [Women’s Health Organization and Mobilization]. The flyer came from the personal archive of downtown performance artist Lucy Sexton (of DANCENOISE). But I had also come across that graphic over the summer, doing research in the archives of Robert Garcia, a prominent ACT UP activist and founding member of the House of Color video collective. I found photos of him wearing a WHAM! shirt with the same graphic—both at a family birthday party and in bed with his partner. Garcia’s wearing of the shirt demonstrates his affinity with and debt to the organizing of the women’s health movement, a lineage and intersection that we hoped to point to in including the graphic that evening. Burk mentioned that the photographers of direct actions were often lesbians—this feels symbolically cogent, as lesbians are virtually off-screen in AIDS activist history.

Lesley Farlow spoke of starting the AIDS Oral History Project at the Jerome Robbins Dance Division of the New York Public Library in 1987 as a result of the swift and deadly impact of AIDS she witnessed as a member of the dance community. She spoke of the difficulty of finding the first willing subject, “nobody wanted to come forward”—which ended up being Arnie Zane, the late dance and life partner of choreographer Bill T. Jones. The interviews were focused on recording the artistic vision of the artist but often ended up opening up onto their larger biographies. Like Román, Farlow pointed to the impact of AIDS not just on dancers and choreographers, but also writers and critics. In addition, through her graduate work at NYU, Farlow looked at the impact of AIDS on dance performance and aesthetics. Farlow ended her talk by encouraging everyone to go into the library and to sit down and listen to the oral histories. “Don’t read the transcripts,” she said, explaining that the voice itself communicates—through inflection, pauses, timbre—so much more than the words themselves.

Janet Werther showed slides and discussed her recent archival research on John Bernd, the downtown dance artist who was the initiating force of the Platform, and a close friend and colleague of Ishmael Houston Jones. Werther spoke of her emotional response to doing this work (“I wish I knew him.”), encountering the ephemeral evidence of tear drops and mouse poop, and the ethical issues that arise in working with archives that implicate an “entire cast of characters, some of whom are still living.” She also spoke of the relationship she was observing, through working in Bernd’s archive, between release technique and AIDS—more on that can be found in this interview.

Thomas F. DeFrantz’s presentation/performance began with music: first, a few isolated piano chords, and then Donny Hathaway’s singular voice, singing “A Song for You.” Layered over the melancholic and heart-twisting beauty of Hathaway’s song, DeFrantz spoke, traveling at his own sure and syncopated pace, weaving together the lives of three men: Alvin Ailey, Donny Hathaway, and Dudley Williams (one of Ailey’s most celebrated male dancers who passed just a year ago). While the event of Ailey’s work Love Songs (1972)—created for Williams to the soundtrack of Hathaway and Nina Simone—brought the three men together in history, DeFrantz wove them into a larger story about the “offstage shadows that haunt black performance,” especially for black gay men from the 80s and into the present. In the midst of racism, mental illnesses, trauma, homophobia, DeFrantz said, “HIV/AIDS lands ‘in the middle, somewhat elevated.’” [In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated is the title of choreographer William Forsythe’s heralded 1987 ballet, commissioned by Rudolf Nureyev for the Paris Opera Ballet]. Exposure and isolation, due to the risk of being “punished for stepping out of the shadows,” by peers and white critics alike, emerge as twinned threats as DeFrantz followed the career of Ailey (and by association, other black gay male performers). In the song, Hathaway sings, I’ve acted out my life in stages/with 10,000 people watching.

“The archives, in chasing history, were their own shadowed refuges—places to be quiet and imagine other possibilities,” DeFrantz said, pausing before repeating, almost under his breath: “other possibilities,” as though acknowledging the limits inscribed even in that utterance. In his 2004 book, Dancing Revelations: Alvin Ailey’s Embodiment of African American Culture, DeFrantz frankly discusses Ailey’s sexuality and AIDS-related death—both of which had been withheld from public confirmation. He spoke of doing this research, the resistance he encountered and how, going through with it, “the room shifted ever so slightly, but not much.” In the last section of his presentation, DeFrantz took up the current moment and the project of examining the intersection between black performance/black aesthetics and aesthetics informed by HIV/AIDS. Pointing to HIV/AIDS as one threat among many to black life and black creativity, he stated: “We always already know that black creativity is always circumscribed by black death in the face of white disinterest and fear.”

DeFrantz’s presentation, insistent and almost incomprehensibly layered, reminded me of Lesley Farlow’s request that the voice be attended to—with the presence of DeFrantz’s voice, Hathaway’s voice, the sound of the piano, and the silences, “the room shifted, ever so slightly,” into a space of feeling and urgency that did not feel at all relegated to the past, but that implicated and involved all of us right there and then.

* * *

A Matter of Urgency and Agency brought together a remarkable group of activists and cultural workers who have been working on a range of current initiatives related to HIV/AIDS: Jawanza James Williams of Voices of Community Activists and Leaders (VOCAL-NY), Theodore (ted) Kerr, writer and organizer, Kenyon Farrow, essayist and US & Global Health Policy Director for Treatment Action Group (TAG), Robert Sember, Assistant Professor of Interdisciplinary Arts at The New School’s Eugene Lang College and member of the sound-art collective ultra-red, and iele paloumpis, dance artist and death doula. Ted Kerr was responsible for bringing the work of each of these incredible people to my attention, and I am so grateful to him for doing so.

The day after the election, I emailed all of the participants in a slight panic: What do we do now? I knew that as activists and as members of communities directly impacted by Trump’s campaign, everyone would be juggling tasks and emotions. We tossed around various ideas. Rather than extended individual presentations, Robert Sember expressed the hope that we could move quickly into an “open exchange that is appropriate to feeling the shape of this contemporary moment, which requires that we remember the formidable resources and knowledge we already have at hand as we register the shock of having fears become reality.”

In his co-curator essay in the Platform catalogue, Will Rawls expressed a similar sentiment, back in August: “It seems obvious to me that we no longer have the option to live in linear or straight time. We circle back to retrieve, stay here to stake claim and move forward to imagine all at once.” This stance of aware and ready resilience was apparent in the conversation that took place on Nov. 10th. In the face of reflexive despair and fear of the unknown, all five speakers helped us to regain a sense of equilibrium.

iele paloumpis started the evening with a breathing and visualization exercise. Although geared towards activist work, in counterbalance to the previous event which was oriented around the work of academics, we were still in an academic space, and this activity signaled a departure from the standard expectation that we were present in our minds only. Breathing deeply and attending to the sensations of our bodies at that moment afforded us the opportunity to return to the bodies that many of us jumped out of when the election results were announced.

As the evening progressed, there was a consistent redirection back to the body—the somatic body (knowing through sensation), the surveilled body, the social body. Each panelist brought specific concerns and experiences to the table, but in each case, the need for transformation of the entire body politic—the need for integral, holistic systems rather than reforming what is not working—was reinforced. In the face of the collapse of ACA and/or Medicaid, which everyone agreed is inherently flawed, Kenyon Farrow cited this moment as an opportunity to ask ourselves: “What do we really want?”

Robert Sember, quoting the activist Ruby Sales asked, “Where does it hurt?” This question points to the body, helping us to locate the somatic effects of our circumstances and acknowledge pain and fear, but it points to the body politic—what communities are hurting, who most needs help? Ted Kerr presented us with questions gesturing towards communities which are most vulnerable to shifts in HIV/AIDS policy, asking us to think about the intersection of policy with prisons, criminalization laws, everyday life chances, and anticipated new/increased challenges instigated by trauma and depression.

iele paloumpis relayed the stories of two of their clients who they work with as a death doula, detailing the correlation between generational trauma, systemic racism, an ineffective health care system, late diagnosis, and the isolation of living with a terminal illness. they introduced disability justice into the conversation, explaining that, unlike a “rights” model, which is a single-issue approach and focuses on access to pre-existing structures (and HIV/AIDS is considered a disability covered by ADA), with disability justice, we see a shift from “there is something wrong with my body” to “there is something wrong with society.” Later, they suggested, I think only half-jokingly, that we might try “doula-ing the system.”

Jawanza James Williams, who is originally from Texas, also spoke to the need for services (money) to go to the South, where serocoversion among black gay men reflects “a proximity so close—like skin.” Kenyon Farrow also spoke to the continued lack of access to treatment in Southern states, and how the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was crucial for those communities. Although he expressed confidence that not all is lost with the coming election and that we would come through, “individual people will not make it,” he said—meaning those who are most vulnerable. Robert Sember pointed to the “incapacity of the market to deal with questions of justice and well-being.” Jawanza spoke of an expanded and holistic approach to HIV/AIDS services, offering, for example, that “housing is healthcare,” and suggested that attention be paid to seroconversion of communities rather than on the individual level. When no money is available, he reminded us, people are resources—it can’t be done alone.

“We’ve been here before,” said Kenyon, noting that in general black people were not as shocked as white people about the election results. “I think about Reagan, Nixon, Plessy v. Ferguson, the rollback of Reconstruction, 1876 and Rutherford B. Hayes.” [Republican President who won a drawn-out electoral college deadlock by corrupt means when he agreed to reverse Reconstruction.] Also speaking to being-here before, Robert Sember described holding his partner’s crumpled body the night of the election—it “opened territories of suffering.” “We are places where things happen,” he said. “In moments of trauma, the archive comes alive.” Those who lived through the AIDS Crisis, along with black, brown, Asian, and indigenous communities who have lived through any period in this country, know, deep within their bodies, that government neglect has disastrous effects.

Bodies also remember resistance—and sometimes this resistance looks political and sometimes it does not, but it nonetheless it makes it possible to live. Kenyon’s somatic memory was activated when Robert Sember began speaking about his connection to the house and ball community. I saw it in his whole body as he leaned forward while Sember spoke. During the open conversation, he said, “I’m thinking about art and culture—thinking about the political space through which AIDS as a crisis emerged.” A self-identified house-head, Kenyon recalled the importance for him in the 80s and 90s, of accessible, inexpensive parties—cultural spaces where bodies packed in close. Recollecting the music and the lyrics, he said: “I have myself been on the dance floor and had people just bawl—really just lose themselves in that moment.” One of his favorite songs from that time is “Inspiration,” by Kerri Chandler and Arnold Jarvis (1994). He spoke the lyrics into the microphone. It just may be what we need to hear at this moment: “You’re an inspiration to me. / Let’s celebrate life / in the name of those not living.”