Over the last 5 years, academic, writer, and videomaker Alexandra Juhasz and writer and organizer Theodore Kerr have enjoyed a public conversation project around changes within the AIDS media ecosystem. In the text below, they build upon two previous conversations where they discussed movies like The Dallas Buyers Club, How to Survive a Plague and the HBO remake of The Normal Heart to explore how and why media about AIDS has only relatively recently begun to take up space in public after a long silence. Previously, they reflected upon how a good deal of what is currently being made, seen, and talked about stays rather narrow in its focus, looking at stories of the epidemic’s impact on primarily white, middle class, often gay men and their communities. Here, looking at their own past work and how this conditions what they as researchers, scholars and activists look for and want to save, Juhasz and Kerr begin to consider what might be needed so that many inheritances of AIDS could be salvaged, shepherded, and mothered into a legacy of plenty.

—

“You know how it is when people die? Folks always be putting words in your mouth. This way, if I don’t say it on tape, I ain’t say it baby.” These words are spoken by an actress in Grandma’s Legacy, a video where she is playing a soon-to-be-grandmother living with HIV. The tape is most likely from the mid-1980s and was created by Bebashi, an AIDS Service Organization in Philadelphia. Our uncertainty about most of the details of the tape’s provenance, despite several attempts to research it, demonstrates what will be a recurring question in this discussion about the patrimony of AIDS history: who is authorized and empowered to pass on what to whom? We will consider what might be needed to keep all of our valuable inheritances live. This seems critical, given that, while saving people’s lives in the present was a primary concern for the making of AIDS tapes, some of the impetus to make activist videos in the first decade of the crisis was also to claim a well-deserved place in what would become history, especially given that this was a time of so much loss.

Taking the Bebashi tape at face value, one of Grandma’s legacies is a bridge to a neglected past via a VHS dub of a DIY-educational video project. In it, she speaks proudly and publicly from her time, and yet somehow she has been quieted in today’s making of AIDS activist history.

In the tape, she discusses with her daughter the reason they are making a videotape about AIDS (in what is the final chapter of a series of short video vignettes that focus on the impact of domestic violence, poverty, drugs, and HIV/AIDS on black women); the daughter is recording her mother’s life story for “the sake of posterity.” The grandmother does not believe that she will live long enough to share her life story with her grandchildren, one of which is soon on its way. We see the grandmother primarily through the camera, the eye of her daughter. Occasionally, when the grandmother expresses doubt about telling her story on tape, we get a shot from a different perspective and see the two women sitting across from each other—the camera now acting as bridge between generations: the daughter and mother in the tape; the activist, feminist, womanist of color legacy of AIDS; and Ted and Alex (and you, the reader), the seeking viewers of today.

Grandma’s Legacy is one example of the numerous activist videos made in the US during the early response to HIV. Taking up new and affordable camcorder technology to create culturally specific tapes regarding the AIDS crisis, these tapes by and for the communities most impacted by AIDS, then and now—people of color, women, trans people, and people living in poverty—would be played wherever there were VHS players and monitors: in churches, multi-purpose rooms, on cable access and mainstream television. Made for diverse audiences, they shared a commitment to foster more realistic depictions of and informed discussion about HIV/AIDS. This tape-based method of community organizing and video activism within the early stages of the North American AIDS movement has largely been lost as have many of the tapes themselves. However, they exist as testaments to what we now call “intersectional” strategies, and they are waiting to be recalled by and re-gifted to a present that seems to have misplaced and could very much use this legacy.

This summer was the first time Ted had seen Grandma’s Legacy. It was one of many viewings for Alex. The video was pulled from Juhasz’s personal archive of AIDS tapes, which Kerr and she watched together at her home. Some of the tapes were digitized in 2015, as she prepared to move from California where she had lived, taught, and written for 20 years, back to NYC where she had begun her career writing about/making AIDS tapes while participating in early AIDS activism. Juhasz had amassed her archive initially as research for her dissertation that would become her book AIDS TV: Identity, Community and Alternative Video (Duke University Press, 1995). Stacked on her office shelves in their original VHS format, most of the tapes had gone largely unseen since she had first made or acquired, viewed, and written about them in the late 1980s. The act of re/viewing and the lessons they provide for activism and media making today organizes the conversation below.

In previous conversations Juhasz and Kerr have identified, discussed and refined a timeline of an AIDS media ecology that begins with a highly active period of AIDS media making and dissemination (1986-1996); followed by the Second Silence (1996-2008), a period of reduced creation, dissemination and attention to AIDS related media; to the present moment, the AIDS Crisis Revisitation, marked by a notable increase in the production and dissemination of AIDS related media that looks back at the early days of the known AIDS epidemic often using video footage from the past (mid 2000s-ongoing).

Films like Dallas Buyers Club (2013, Jean-Marc Vallée), How to Survive a Plague (2012, David France), United in Anger (2012, Jim Hubbard), We Were Here (2011, David Weissman) Sex Positive (2008, Daryl Wein), Larry Kramer in Love and Anger (2015, Jean Carlomusto), Back on Board (2015, Cheryl Furjanic) and The Normal Heart (2014, Ryan Murphy), to name only a few, have been widely seen, earned awards, and captured the minds and imagination of a cross section of communities. They have brought together those who lived through the early days of the crisis and those who, generations later, are inspired by and interested in how communities responded to a plague that was being ignored by the government and other powerful players in public health, medicine, and mainstream media.

Films from the AIDS Crisis Revisitation are inspiring and enable discussion of a chapter of American social movement history that is little told in more formal educational settings. Yet, as we and others have noted, there is a troubling sameness around who and what is being historicized.[1] These media offerings primarily center on the stories of white, middle class, often gay, cisgender men. In the films, these men are depicted as the dominant, and sometime only demographic of people living with HIV, as well as those largely responsible for fighting against public apathy and governmental neglect. However, AIDS activism might be understood to be successful at this earlier time precisely because multiple communities and constituencies suffered and also struggled to achieve both discrete and shared activist goals. For example in How to Survive a Plague, we see a small group of mainly white gay men who fight to secure life saving medication. But Revisitation films rarely show the many other constituencies within ACT UP, as well as other activist groups, who developed their own appropriate tactics to reach other goals. For example: too little known is the story of how women living with HIV in prison were foundational in the fight to have the definition of AIDS changed in the US to include them, a reality that came to pass in 1993. Where is the movie of that story?[2] Missing is the story of Other Countries, the ongoing writing collective of black gay men, who in the early days of the crisis came together to write about what was happening to them and the people they loved in the face of the epidemic. Missing is the story of Latino activists who worked to get meds for people across the Americas during the early days of an epidemic that knows no borders.

Lost within the Revisitation is the fact that AIDS activism grew out of the rich traditions of the civil rights, gay rights, and women’s health movements. The North American AIDS activist and not-for-profit landscape was much more diverse, fertile and complex than the current revisitation lets on.[3] At the time, a rich amalgam of local AIDS organizations targeting particular communities, as is true now, developed and enacted a range of tactics that reflected their constituencies and concerns. The footage and narratives that reflect this diversity of AIDS-related realities have not been brought fully forward to the present, rather what we often find before us looks like a patrimony: a circulation of images and ideas primarily focused on white gay men.

Which is not to say that gay white men did not suffer and die from HIV in numbers both criminal and devastating and are not still deeply impacted by the disease. They were and they are. But, they are not alone and never have been. Currently in the US, around 1 in 4 people living with HIV are women,[4] and as the Center for Disease Control reports, “Blacks/African Americans have the most severe burden of HIV of all racial/ethnic groups in the United States.”[5] As of 2014, “44% (19,540) of estimated new HIV diagnoses in the United States were among African Americans, who comprise 12% of the US population.”[6] And these numbers don’t show the populations that fall out of statistics. For example, only recently have trans women and men been counted at all. Rather, for most of the crisis they have been recognized as either cis men or cis women. Advocates argue that this disappears the reality of folks while also providing inaccurate insight into people’s health and well-being,[7] and instead reflects embedded and outdated ideas of gender, identity, risk and prevention.

It is here where different stewards of video activism and the AIDS archive can help to make a break into history, revealing more complex and diverse narratives and strategies than those that are otherwise more readily available, be it through the Revisitation, statistics, or the many other ways in which legacies are saved and passed on. In reviewing Juhasz’s tapes, we found that in contrast to the urgent yet narrow view of history being expressed via the Revisitation, the past is filled with video work largely ignored, video that was created by and featuring a diversity of makers and communities. In the discussion below, we work together to begin to respond to the questions: how did we get here and what else is there to save, see and pass on?

—

Ted: Coming up in Edmonton, Alberta, in the late 1980s and 1990s as I did, where it seemed like no one was talking about AIDS at all, I can’t fully convey to you the overwhelming feelings raised by going into your archive and seeing the enormity of what had actually been created and what I had never seen. I think for people of my generation and younger there is a sense that the educational and cultural inheritance we received around HIV/AIDS lead us to feast on scraps. We took what we could from whatever we could get our hands on, which was primarily prevention posters, memories of our own encounters with mass media, and stories from elders, primarily rooted in a pre-1996 reality. To have known and had access to a more diverse array of AIDS activist video would have blown me away and most likely changed the trajectory of how I came to understand HIV/AIDS. At the very least, I would have been more secure in my awareness that not only was AIDS not over but that it impacted folks beyond the gay male community.

Alex: A hard thing being an aging activist is determining when it is appropriate to share stories and strategies from the past. On a personal level, although I lived and worked in the past, I am now part of present-day struggles. Looking backwards is often detrimental to attending to the most important tasks at hand. But, as critically, people working in the present often see the ideas, tactics, and troubles of the past as dated, tiresome, or overstated. There are multiple reads of and needs for the past that are live in any multi-generational activist community.

Furthermore, many things that were common sense for one period or generation within a larger activist history stay common sense for those who experienced or developed them but lose this familiarity for people who enter the movement later. For instance, the fact that there was a huge body of unimaginably diverse videotapes that were made by and for the AIDS activist movement, in its stunning complexity, and that for a time these were shared and then used in a variety of activist contexts—from the most remembered and visible activity of taping and sharing street-based activism, to the less remembered forms of what we called “trigger tapes,” (videos like Grandma’s Legacy that were made to be stopped and discussed), or PSAs, informational videos, and artist’s tapes—this feels like something I just know. It wouldn’t dawn on me that I would need to share this history with you, Ted. More so, the fundamental knowledge that AIDS is a crisis experienced disproportionately by poor communities of color, half of whom are women, is simply a known known for me. I wouldn’t think: I need to share that “from the past.” Finally, I wrote my dissertation about these ideas and tapes, which were developed in lively dialogue within a rich, active, and large community of thinkers, artists and activists, and so I guess I thought I had said it already, as had many of my peers. Why would I need to say it again? And, I hope that you don’t take this personally, Ted, but I did know that you had actually read my book! So how come these ideas didn’t pass forward to you? How come it hadn’t stuck that this archive was as huge, and rich, and multiple, and just plain amazing as I testified to at the time?

The answer, obviously, is not that you are a poor reader, or I hope, that I am an unconvincing writer or videomaker. Instead, we must consider how the range of activist practices and the many possible archives that (might) hold them create the broader frameworks that produce, sanction, maintain and pass on institutional and cultural memory and knowledge. Of course my AIDS TV, and many similar and linked interventions by scholars and writers and activists, testified to the rich complexity and common-sense knowledge of that time, but the stewards of the AIDS archive—the cultural institutions and their workers that were deemed or deemed themselves responsible for saving this history—reflected primarily one section of this community (itself internally complex and varied): the gay white men with the most access to capital and other forms of cultural sanction.

If gay white men and their institutions are the stewards of the AIDS archive—which is what we are suggesting here—of course what is shelved, highlighted, searched for, found, and re-seen will primarily reflect this point of view, an important but partial one. We merely ask: what do other archives hold? What do we find when we read all of Corpus, a journal that came out of AIDS Project Los Angeles created primarily by LGBTQ youth of color? Or look at the history of Gay Men of African Descent? What picture of AIDS activist history and media making would emerge from them? And then, we found an obvious strategy to begin to answer these questions! I had such an archive: small, partial, dated, to be sure. But I had to re-do old work again (that is, screening these tapes and providing a context in which they made sense) to show these videos to you! And it was such a wonder to me, re-watching many of the tapes with you for this project, and then choosing the seven works we would focus on for a larger piece of writing on movement media, that you did not know, could not imagine, somehow had not learned about the amazing images and strategies that we had struggled so hard to invent, mobilize and save. You, a person who had made this your goal! Where had we/I gone wrong? How do we fix this?

Ted: I understand that, as someone who was part of the response to AIDS while it was first unfolding and unraveling all around you in a city with a variant ecosystem of community responses, your very definition of the crisis and the response was and continues to be intersectional and complex. And that, in turn, impacts how you encounter someone like me in this work, and your thoughts and feelings around how AIDS is being memorialized and what is being lost and forgotten as history is being remembered, translated, and cherry-picked. My experience is very different. The only obvious things you and I have in common when it comes to HIV is that we are both negative, white, and deeply embedded in community, meaning our lives are lived among friends, lovers and fellow activists who are living with HIV and/or are deeply impacted by the ongoing crisis.

I often come back to this idea that I am working through a cultural inheritance of AIDS, what we are calling its patrimony. Of course I have read your book, but it took me time to find it, and even then I was reading it through what I knew. The first fifteen years of my involvement with HIV/AIDS was cutting through both the silence and the mainstream ideas around HIV/AIDS as seen in “Special AIDS episodes” of sitcoms, almost always featuring young white men who were implicitly or explicitly gay and who were always tragically dying. And it was not just prime time. On talk shows, the nightly news, and in magazines, white gay men were always pictured as central to the AIDS story, even when it was about women, babies, or “Africa.” Even in the process of moving the story of AIDS away from gay white men, their centrality was reestablished.

Alex: I have to intervene here, Ted, with a sad but telling utterance … duh! What you see as a revelation today is exactly what we knew and showed then: that we had to wrestle the narrative to include women; that women’s experiences of HIV were different from gay men’s; and that a feminist, womanist of color, and what would become called, thanks in part to our work, “queer” critique of dominant representation would be our visual and organizational templates. These strategies were rife across the early AIDS activist landscape, to be quickly lost it seems, except for in my memory (and that of my peers), on my office shelves, and in my book and scores of scholarly articles.

Ted: I guess that is why it seems so important to me to get to the bottom of this stewardship of AIDS archives for me. Because growing up, even in the rare moments that white gay men were not the implicit or explicit focus, my mind had already been trained to read gay into AIDS. As a young gay man it felt nearly mandatory for me to consider HIV—if not outright fear—as part of my identity creation and patrimonial legacy. So what had been, I thought, a personal experience and limitation is actually now structural in terms of the way that the history of how both gay white men and AIDS have been represented in the mainstream. We see this with the allure How To Survive a Plague has. For gay men, and LGBTQ folks in general, the footage of young queer people fighting the system and having a major win is intoxicating. While no such AIDS films existed when I was growing up (or rather, I had no access to the legions of AIDS activist videos that did exist), gay history books and, soon enough, the internet circulated images like Silence = Death and General Idea’s Imagevirus. These became seminal to how I could consider being in the world as a gay man. Volunteering and then working at the local AIDS service organization was about wanting to be part of what I saw: the queer creative effective response to make the world better, through AIDS activism.

Alex: Ted, I think the unpacking you are doing is valuable. But we have to be careful here. As recent conversations with our friend—artist and activist Pato Hebert—have shown us, when we speak so much of gay white men—even when we are working to destabilize the space they/you take up in this conversation and how that came to be—we end up not speaking about black gay men, gay men of color, straight men and other people who may defy easy classification. Even in this conversation it seems that whiteness, man-ness, and gayness have become rigid and too tied together. “Gay,” as an identity and an organizing principle in the ongoing response to HIV/AIDS in the USA and around the world, has been a vital position of strength, solidarity, and resources and can be claimed by any number of people from various backgrounds and life experiences.

My political project has always been to work inside communities to make visible the stories of the most-impacted and yet somehow still least-seen perspectives within AIDS (women, but also poor people, people of color, children, parents, drug users, prostitutes) because I have always understood AIDS to manifest and magnify the larger structural and institutional deficiencies of our society that deny some people equal access to health, education, dignity, safety, and even civil rights. However I remain (self) aware of the role of white people (like us), (gay) men (like you), and those of us who are privileged due to education, class, or other forms of cultural capital in the broader movement. “Intersectionality” is not simply about forefronting the experiences and points of view of people who are shut out of dominant, monocultural depictions of reality and history but also about understanding that there is really no monoculture to begin with: that the dominant position itself, if understood with care and complexity, can and does inspire alliances, as well as more nuanced understandings of the allegiances, motivations, connections and differences which build, sustain and sometimes topple movements.

Ted: Totally. And eventually I got out of the myopic way of viewing HIV/AIDS. My world-view changed because of what I was exposed to, working primarily with women (of color, queer, and First Nation), two spirit men, and a few older white gay guys. From them I received an education in critical race theory, indigenous ideas around community and overall, feminist approaches to public health. They helped me not loose sight of the role of sexuality in the story of HIV/AIDS, nor my own experiences as a person in the world. I remember one time at a public talk about HIV that turned homophobic, my friend and colleague Lynn and I sprung into action, countering lies being told. We began by asking the speakers to clarify some of the more egregious things they said to ensure that we were hearing them correctly, then we took over the space, turning it into a teach-in around the social determinants of health. When a woman from the audience said that she did not know any gay people, I swiftly corrected her saying something to the effect, “ You do now. Me.” In the car home that night I felt high and told Lynn as much. She said that feeling was the best of what can happen when we allow the personal to be political.

As I came to find out, no matter how hard I try to keep ideas of “gay” and HIV/AIDS separate, there is a meaningful connection between them. Finding the balance is really important. After years of thinking about HIV almost solely though a gay lens, I then went too far the other way. I became nearly intolerant when hearing HIV history related almost solely through the lens of “gay men.” I had to learn to think about my sexuality in both personal and political ways.

Alex: It’s interesting to hear this from you here because what drew me to you was precisely your enthusiasm, energy, and optimism, particularly in relation to what had always been core to my AIDS activist work that centered the experiences of women, people of color and lesbians. You were cutting a new space for this (old) work, and that was so invigorating.

Ted: My cynicism cracked in early 2016, when I was given a tour of the Schwules Museum in Berlin. A longtime volunteer explained to me the evolution of their collection. It started by acquiring with the gay experience in mind, then evolved to consider lesbian, bisexual, and eventually the trans experience. But from the beginning of the known AIDS crisis, the museum collected everything on the subject regardless of identity markers, and as a result, they have a cohesive HIV archive. It was clear, in his telling, that the museum’s trajectory was an emblem of pride. Not only was he proud to be a volunteer with the Museum, he specifically wanted to impress upon me the deep and vast AIDS-related holdings that they had. In talking about this, a word came up: stewardship. The museum was acting as a steward of an expansive and complex AIDS history, one that early on recognized that the crisis impacted all kinds of folks and an implicit understanding that AIDS was a gay concern. Within the belly of burden was also the notion of responsibility to represent AIDS not just as it impacted gay, lesbian, bisexual and trans folks, but everyone. Having this interaction freed me from the near intolerance I was often facing, and instead gave me a bird’s eye view on how we could see the AIDS archives within the gay domain being constructed, and what could come of this choreography of history.

In months since, I have come to learn that a lot of AIDS-heavy archives live within LGBT-focused archives. In Norway, for example, Norge-HIV recently donated all their papers to the nation’s LGBTQ archive in Bergen. And closer to home, even your own records at the New York Public Library’s large holdings of HIV related papers and artifacts is part of the Gay and Lesbian Collections. Similarly, StoryCorps, which arguably began when the founder interviewed his straight neighbors living with HIV on the Lower East Side about their lives, has an initiative to collect stories about HIV but this too lives under their LGBTQ initiative.

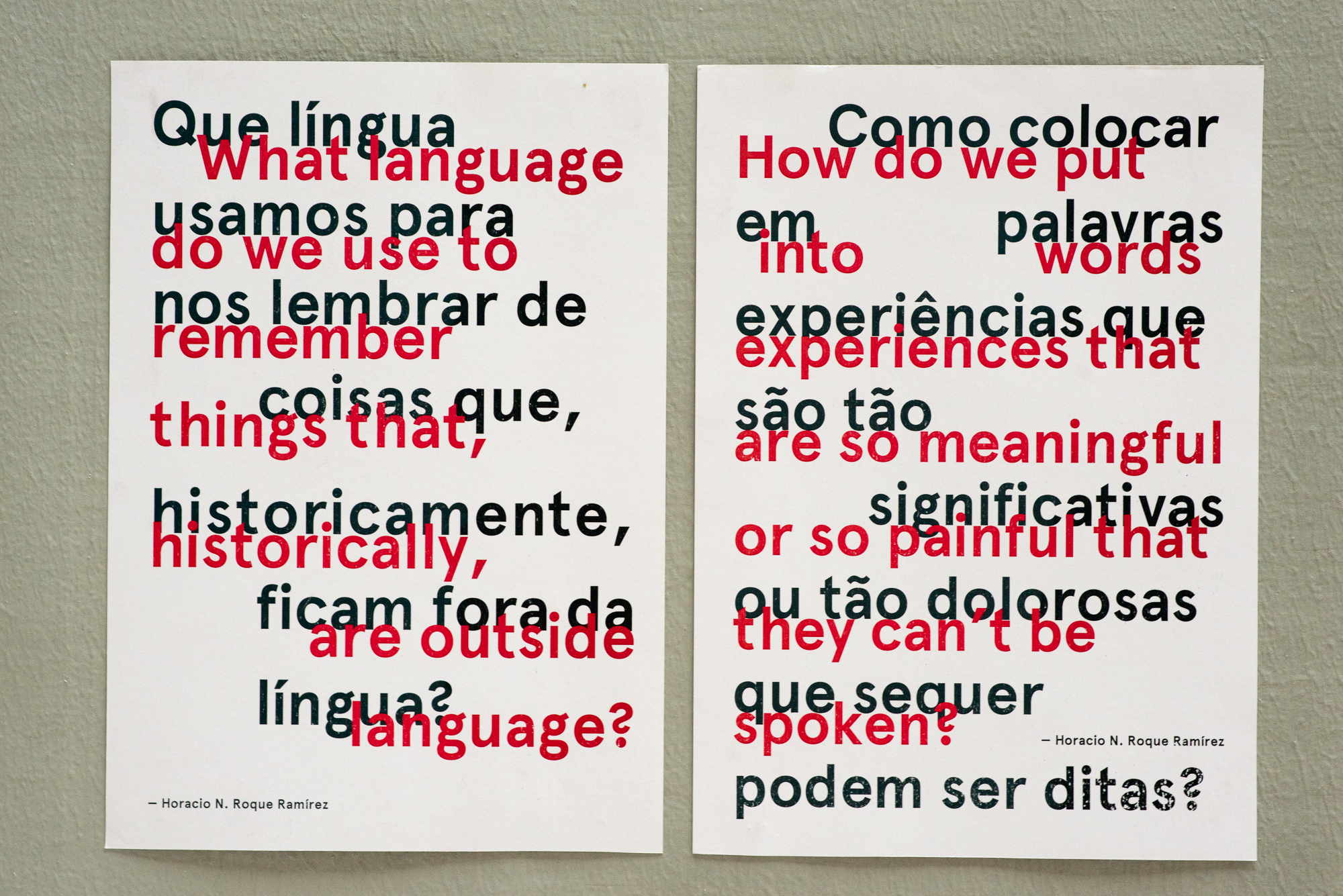

I am excited about your tapes because they open up the possibility to see HIV/AIDS both through an LGBTQ lens, but also beyond and with other lens. Or maybe to put it more productively, I want to wrestle with something you tackle in AIDS TV.[8] Early tapes about AIDS were important, vital, and effective because they worked to challenge dominant depictions of reality that looked little like the day-to-day lives that people experienced in relation to HIV/AIDS and other things. Decades later, a lot of those day-to-day experiences have not been pulled forward into our historical remembering. And that is a shame, because on top of communities and situations not being represented within much of the current AIDS Crisis Revisitation, further lost is the already ineffable. I am thinking now of 2 questions Pato brought to our attention. His friend, Horacio N. Roque Ramirez, a sociologist whose groundbreaking work focused on queer Latina/o oral histories, asked: “How do we put into words experiences that are so meaningful or so painful they can’t be spoken? What language do we use to remember things that, historically, are outside language?”[9]

When we watch a tape like Grandma’s Legacy, we are not only seeing a black woman living with HIV (although the importance of that cannot be understated), we are seeing expression, concern, movement, embodied by the actresses, caught on videotape, that are specific to a place, time and experience: Philadelphia, late 80s, a black woman with her family in search of support. We know what history looks like if only those with most access save, pass on and then retell it. By putting Grandma’s Legacy back into circulation we take one small step, with many others, to begin to make this history more complete. There are more stories, more realities, more experiences of living with HIV than we will ever be able to share. But that does not mean we should not try. The only thing worse than knowing what has been lost to history is not knowing what has been lost to history.

Words by Horacio N. Roque Ramírez (1969-2015); Photo by Pato Hebert; Poster by Edições Aurora / Publication Studio SP. Courtesy of Pato Hebert.

Words by Horacio N. Roque Ramírez (1969-2015); Photo by Pato Hebert; Poster by Edições Aurora / Publication Studio SP. Courtesy of Pato Hebert.

Footnotes

[1] Most notably, in his essay “How to Survive…” for Women Studies Quarterly, Jih-Fei Cheng writes about how recent films primarily depict “AIDS activism through the lens of white male heroes,” resulting in women and queers of color being “marginal in these films,” and appearing “only in order to go missing by the narrative’s end.” Similarly, in his essay “Under the Rainbow” for The New Inquiry, Tyrone Power writes about how the revisited histories “appear in memory as decidedly white and middle-class.”

[2] That tape is in Juhasz’s small private archive. Debra Levine and Catherine Saalfield’s I’m You, You’re Me: Women Surviving Prison, Living with AIDS (1992). See this and more tapes discussed in Saalfield’s Annotated Videography in AIDS TV.

[3] See: Alexandra Juhasz, “Forgetting ACT UP,” Quarterly Journal of Speech, 98 (2012): 69-74.

[4] “HIV Among Women,” Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Accessed August 22, 2016, http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/

[5] “HIV Among African Americans,” Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Accessed August 22, 2016, http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/africanamericans/

[6] ibid.

[7] W.O. Bockting et al, “Transgender HIV prevention: A qualitative needs assessment,” AIDS Care, 10 (1998): 505 – 525; “HIV Among Transgender People,” Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Accessed August 22, 2016, http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/

[8] In a passage quoting Claire Johnston, Juhasz is interested in the role of self-representation in the work of social justice. AIDS TV (Durham: Duke University Press, 1995), 79.

[9] The questions are from the essay, “Sharing Queer Authorities: Collaborating for Transgender Latina and Gay Historical Meanings” which appears in Bodies of Evidence: The Practice of Queer Oral History, eds. Nan Alamilla Boyd and Horacio N. Roque Ramírez, Oxford University Press; 1 edition (February 17, 2012) Pato Hebert shared Horacio Roque Ramírez’s work during (Re)sent(i)ment, a community dialogue that occurred at Casaro do Belvedere in Sao Paulo as part of Cidade Queer, a collaboration between Lanchonete.org and Musagetes. Hebert first encountered this particular quote in Alamilla Boyd’s remembrance of Roque Ramírez. Edições Aurora / Publication Studio SP heard the quote during the (Re)sent(i)ment event and translated Roque Ramírez’s insights into Portuguese and then designed and disseminated two posters. The posters were created for Ataque!, a community house ball held outside Praça des Artes in Sao Paulo on September 10, 2016.