This spring, the pilot program of the Collaborative Research Seminar on Archives and Special Collections welcomed a cohort of twelve students to participate in two sessions—one at the Graduate Center Library, and the other in the Brooke Russell Astor Reading Room of the New York Public Library. We collectively discussed methods for engaging primary source materials in our research at the Graduate Center, CUNY, and encountered a variety of archival and rare materials—Timothy Leary’s papers, commonplace books, Patti Smith’s notebooks, books in parts, and many more. As a group, we grappled with a wide variety of questions, from citation management to experiencing enchantment, and what it means to encounter primary source materials as embodied readers in space and time. A few of our participants volunteered to share their reflections on this process in the form of blog entries, which we are excited to share in the months ahead as documentation of the work we accomplished together and as examples of the possibilities primary research affords.

In this second post of our series, Cory Tamler, a student in the PhD program in Theatre at the Graduate Center, CUNY, brings her disciplinary background in performance studies to bear on a copy of the SCUM Manifesto, selected for the Seminar by Thomas Lannon of the New York Public Library. This book, published by Olympia Press in 1971, is held in the Manuscripts and Archives Division of the New York Public Library, and is heavily annotated by Valerie Solanas herself. With close attention to bibliographic detail, Cory discusses the act of annotation as a textual performance of becoming for Solanas—who negotiates the text’s unique publishing history and its consequences for her legacy in both the literal and figurative margins.

-Mary Catherine Kinniburgh, September 2017

Annotating and Becoming: Valerie Solanas on Valerie Solanas

Cory Tamler

September 2017

As a performance scholar I found myself drawn during the Collaborative Research Seminar to self-annotation: as a residue of temporality in archival materials, as a Krapp-like performative conversation with the self across time. For this post, I spent time with the SCUM Manifesto, a seminal feminist polemic annotated by its author Valerie Solanas. Solanas is also remembered as the woman who shot Andy Warhol—an act occasionally interpreted as an actualization of the ideas in the manifesto, which opens with a paragraph that exhorts “civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females” to “destroy the male sex.” Her annotations here speak to particular views and controversies legible at length elsewhere—for example, her assertion that her publisher wrested authorial control from her, inducing her to release a self-published version. These annotations also place the New York Public Library as archive and public memory repository in conversation with itself: the “defaced” copy is one that Solanas checked out from the Library in order to mark it up before returning it to circulation [1]. In the spirit of the Seminar, I approached the annotated volume as an object of potential that speaks to the act of annotation itself, an annotation as a living gesture that brings a text into a new kind of relationship with different layers of time.

The book’s red cover is scraped raw by Solanas’s black pen marks. She’s crossed out her own name under the title with such vigor that in places the white pith of the paper cover shows ragged through the red and black. Drag the pad of your finger over it, you’ll feel the torn surface. Beside it, she’s written “by Maurice Girodias,” as if to reassign authorship to her publisher. Her name, though, is still legible—the act of defacing was more important than the actual erasure of information, as if she can’t decide between protesting the personal (male) affront and asserting her authorship. In fact, annotation allows her to do both at once.

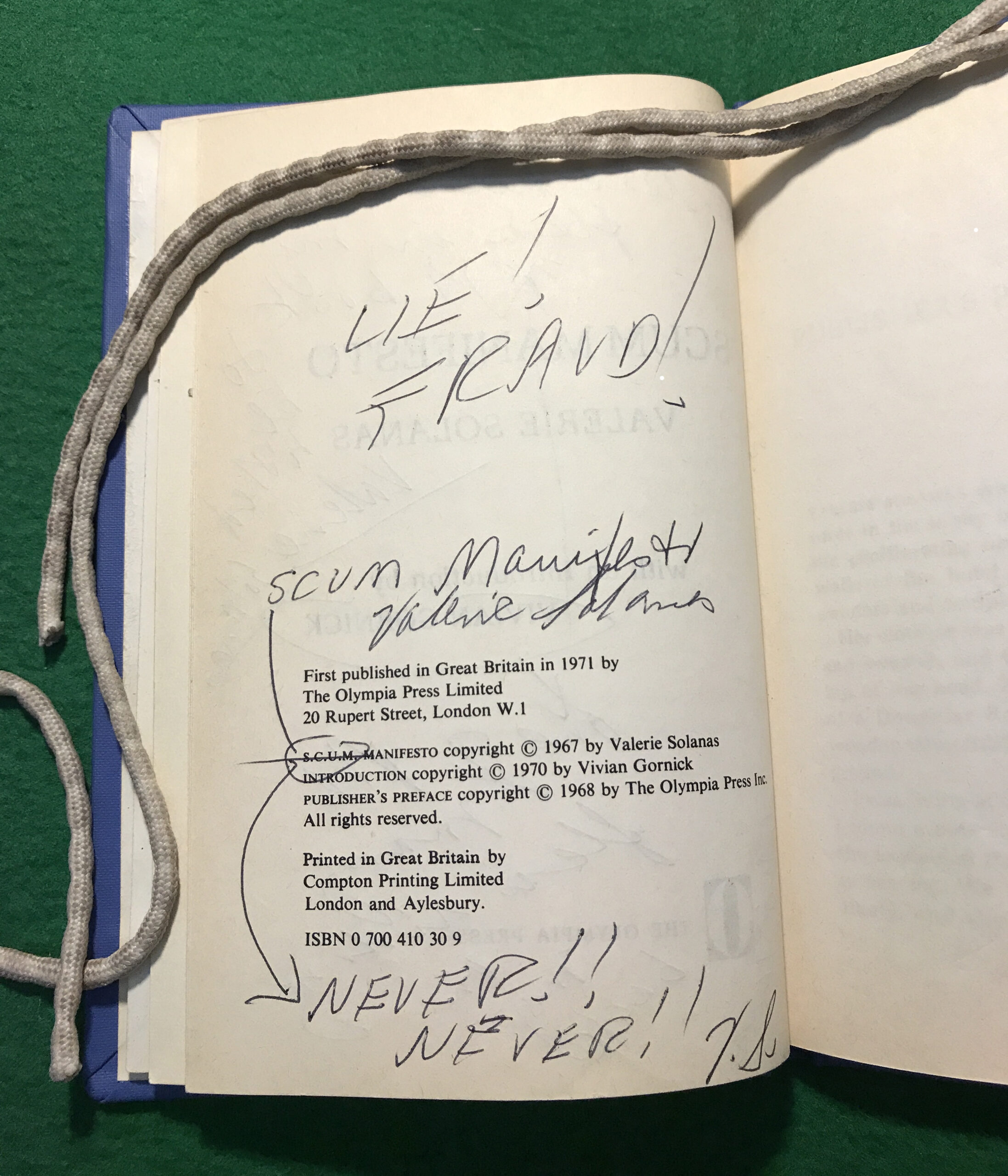

Throughout the book it’s the periods added to SCUM that seem to evoke the angriest reaction. The appellation is (re)written on the covers and the title and copyright pages as “S.C.U.M. (Society for Cutting Up Men)”. “This is not the title,” Solanas writes beside S.C.U.M. (Society for Cutting Up Men) MANIFESTO on the cover of the annotated volume, and signs her name. Flipping to the copyright page, you find “S.C.U.M.” circled, slashed through with a horizontal line, and elaborated with the commentary, “NEVER!! NEVER!! V.S.” While it’s true that SCUM is never referred to within the manifesto text as an acronym for anything, Breanne Fahs notes that the expanded term appears at least in an audition notice posted publicly by Solanas [2] and in a Village Voice ad she wrote in 1967 [3]. Her insistent handwritten denials here mark the passage of time distinctly. A major event has happened since 1967: Solanas shot Warhol in 1968, and the edition she’s marking up sensationalizes this unashamedly (in the preface, in the introduction, on the back cover) to package the work. It transforms Valerie Solanas into an object to be considered with horrified fascination rather than the thinking, acting, radical subject she wants to be. It paints her as a woman caught within the broken logic of maleness: a male female, to use her term. Male females are, according to Solanas, the real enemy. Little wonder she would deny an expansion of “SCUM” that can be used to support this picture.

The names of things are important. It’s not just the title; it’s names other than her own that provoke a reaction from her. It’s like she wants to drown them out. The name of the author of the introduction, writer Vivian Gornick, is circled and explained to be “one of the fleas riding on my back,” a statement that’s signed “Valerie Solanas.” She calls Gornick and Girodias out by name. She calls out his “flea copy editor” by name. The epithet she chooses is telling. Girodias, Gornick, et al are all “fleas.” They’re parasites and she can’t seem to bear their presence in the book. She wants them eradicated, exterminated. She sprays her own name liberally across the pages like a pesticide, punctuating most of the annotations with her own name or initials.

Though the first few pages are crisscrossed in markings, giving the impression of abundance, the interior annotations are few. Despite her early handwritten note attesting that the book is “full of sabotaging ‘typos’ & Girodias’s flea copy editor…changed words,” Solanas doesn’t point any of them out within the text. On the back cover she returns with a vengeance (and with her black ballpoint), redacting paragraphs and liberally appending “flea” as adjective, writing in tall letters that encompass half a page: “LIES! LIES!” The amount of attention paid to the covers suggest a preoccupation with the book’s presentation and, indeed, at times the annotations read like an ad campaign. In one, she writes, “Read all about fleas in my next book to be titled Valerie Solanas.”

For whom did Solanas mark up this volume? In whose hands does she imagine it, her wounded book? Is she leaving notes for the fleas? For SCUM? For S.C.U.M.? For future scholars or archivists? For a past version of her own self, in assurance that she hasn’t forgotten what it is she set out to do? For whose eyes is it meant when she turns to the back cover and, in the sentence “Then we were horrified when she shot Andy Warhol in 1968, just to make a point,” crosses out the final clause and writes above it “lie”?

During the Collaborative Research Seminar we tried to think beyond the limitations of the practical and to imagine what might be possible within archives. I got fired up by instances of time leaving marks in an archive, on an object; an object’s temporal layers. What drew me to the annotated SCUM Manifesto is the way it contains two characters who are the same person. It’s a record of a conversation between the author and herself, but it’s a performative conversation, enacted for an audience (but what audience?) that was already historicizing her through public characterizations of her sexuality and mental health. It resists the freezing action of historicization, existing within time dynamically.

In her annotations, Solanas responds to who she was, and to what she’s becoming. As framed by the fleas, she’s becoming the angry feminist who shot Warhol. She’s becoming the mad ideologue who would insist we need to “destroy the male sex.” Solanas sees and responds to her book as a performance affected by personal scandal and shaped by exterior critique. Her response to this performance is another performance that looks backwards, outwards, and forwards. Back at Solanas before the fleas infested her book. Out at whomever she imagines is listening, including the fleas themselves. Forward to her next book and its readers—and perhaps to future audiences, to me, sitting in the Brooke Russell Astor Reading Room, weighting down the pages with little beige snakes of fabric filled with sand. To anyone experiencing the odd sensation of a direct infusion, through her fingers, of Solanas’s brilliance, urgency, instability, and rage.

-Cory Tamler

[1] Breanne Fahs, “The Radical Possibilities of Valerie Solanas,” Feminist Studies, Vol. 34, No. 3, The 1970s Issue (Fall, 2008), pp. 591–617, http://www.breannefahs.com/uploads/1/0/6/7/10679051/2008_feminist_studies_fahs.pdf. Another behavior of time in archives: its slipperiness. Fahs, a noted Solanas scholar, dates the NYPL edition to 1970, but its catalog record dates to 1971. Additional research will have to be conducted to resolve the discrepancy.

[2] Breanne Fahs, Valerie Solanas: The Defiant Life of the Woman Who Wrote SCUM, New York: The Feminist Press, 2014, p. 145.

[3] Ibid, p. 167.